One Pro’s Advice for Managing Risk in the Alpine

This article originally appeared on Climbing

After 30 years of climbing, I've learned that with a positive attitude, and the willingness to bail, there is no climb in the world to be afraid of. I don’t mean there are no dangerous climbs, nor that I wasn’t scared on some mountains. But I learned that if I am honest with myself--and aware of my abilities--I can choose appropriate objectives that will let me live another day.

This revelation did not come overnight. When I was starting out alpine climbing I thought being terrified to within an inch of my life was par for the course; I was intimidated by the massive scale and I felt a general sense of malaise in the alpine. In hindsight, I realize this attitude was not at all necessary and it likely stunted my growth as a young alpinist.

What I needed most then was experience and a gradual acquisition of skills. I was scared witless because my ambition exceeded my ability. If I chose realistic goals, then there would be no reason to feel fear; I would be in my element and could explore any climb with confidence.

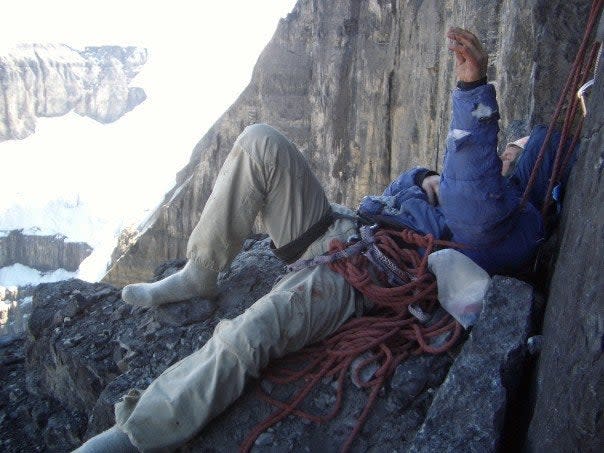

In 2015 I attempted a three thousand-foot first ascent in the Canadian Rockies. We turned around late at night after facing off against a section of difficult and chossy dry tooling. It was my fifth attempt. The next day, over coffee at our boulder bivy in the remote valley, my partner and I debriefed after our attempt. We agreed that neither of us felt disappointed with our effort, despite turning around a mere two pitches from easier ground. We were simply outgunned.

When I was younger I might have been disappointed with this result; failing can make you feel weak and incompetent. I realize now that failure is part of testing one’s boundaries. If you never fail, how will you be able to retreat in the event of an accident? How will you have the courage to attempt a truly difficult climb? Once I accepted the possibility of retreat I felt less fear while climbing. I even started to have fun.

I now enjoy climbs that my younger self would have dreaded. By gaining experience through many miles of alpine terrain, I can analyze a line, make a decision to climb it, and then fully commit. On the biggest line I have climbed, K6 West (7,040 meters), I felt confident in our decision to attempt the face. Others told us the line was threatened by avalanches and seracs. By breaking down and analyzing the climb to understand the skills required--simul climbing and efficient transitions were paramount--we managed the risks. With patience we timed it so that our effort was during a safe spell, when the mountain was shedding little snow, and was climbable. I left base camp curious to see what we would find on the climb. This positive attitude let me perform up to my full potential. I have learned to only attempt big lines which are within the realm of possibility for me--no more flailing around up high. The mileage we gain on easier, safer objectives is a worthy investment.

A decade earlier, in 2004, I was not being true to myself--and my fears--when I attempted the infamous Blanchard/Cheesmond on the 4,000-foot North Pillar of the North Twin. I was terrified by the face’s deserved reputation for rockfall hazard. I just didn’t have the experience necessary to approach such an epic climb with the right attitude. My partner, Chris Brazeau, and I didn’t know how to manage the notorious Rockies limestone, the right conditions to attempt the route, or its history. The difficulties were so far beyond my abilities that fear overwhelmed every other thought. I compare my experience to Steve House’s climb on the same mountain, of which he writes, "We expected to climb until we failed, and as occasionally happens, we didn't fail. Our attitude was old school, the quest for adventure, which is exactly what we found."

This is what I mean by the "right attitude." Steve and his partner Marko Prezelj had the experience and skill required to climb the North Twin. I didn’t. And when I tried to skip several steps in my development as an alpinist, I suffered a huge setback: A falling rock broke my arm on the second day on the Twin and I endured a terrifying self-rescue over the next fifty hours. This failure left me with a confidence deficit which undermined me for years.

On my first trip to the Karakoram in 2006, when we attempted the first ascent of Kunyang Chhish East (7,400 meters), I didn’t leave base camp with the right spirit. We had witnessed avalanches scour the face and fill the valley below; none of us had any experience at altitude; and we were trying to learn about this new environment on one of the most threatened routes I have ever seen. I was exceedingly nervous about the objective and I couldn’t shake the feeling that if anything went wrong we would almost certainly be killed. It was difficult to be honest with myself after travelling so far from home on an expedition like this; I could have easily given up on Karakoram climbing after this one experience.

Kunyang Chhish East was climbed seven years later by a team led by Simon Anthamatten. Simon was mentored by Ueli Steck and his long history at altitude enabled his team to succeed. I can't help but compare my ill-fated attempt to their all-star team. A friend who climbed with Ueli said recently that his advice for Himalayan novices is to do a normal route on an eight thousand meter peak before going big. Get familiar with the environment. That, or stick to lower, more moderate goals for a first trip to Asia. It is not as glamorous as beelining for one of the great "unsolved problems," but it will lead to a more enjoyable and sustainable climbing career.

Young mountaineers will want to push their boundaries. I sure did. I am not trying to discourage them. I have realized, however, that I would have advanced more quickly if I had chosen safer objectives earlier, and had spent less time being gripped by fear. I no longer want to climb routes that are easy but have immense objective hazards. The legendary, and now retired, Mark Twight, noted that he went through a phase when he wanted to be known as the alpinist who climbed highly risky routes. This is not a healthy motivation and should be avoided. No one wants to be known as the climber who died on a famous objective. Though there are the rare climbers who do not wince in the face of extreme objective hazard, for the rest of us, it makes sense to realize that we will advance faster if we are simply enjoying ourselves.

Ian Welsted guides climbers throughout western Canada. He climbs in the mountains for the adventure and friendships formed.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.