One state stands in way of fair Colorado River water cuts. (Hint: It isn't Arizona)

The conundrum of the Colorado River is a tug-of-war between priority and equity.

To adapt to a changing future, the “Law of the River” must strike a balance between the two because, as Thomas Aquinas observed, “law is nothing other than a certain ordinance of reason for the common good.”

Achieving an outcome for the common good will require the foresight of high-priority water users to reach a compromise – or the exercise of the secretary of the Interior’s authority as Water Master to stabilize the system, protect infrastructure and secure the water supplies of approximately 40 million people who depend on the river.

6 states say it's reasonable to share losses

On average, inflows to Lakes Powell and Mead are insufficient to meet demands, including water lost to evaporation and seepage. Lakes Powell and Mead, with a joint storage capacity of nearly 50 million acre-feet, are being depleted rapidly and currently contain about 13 million acre-feet of water in storage.

In January, six of the seven basin states (Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming) proposed a Consensus-Based Modeling Alternative, which recommended that the Bureau of Reclamation model how Infrastructure Protection Volumes, based on estimated system losses, might be shared proportionately between all water users in the Lower Colorado River Basin.

Everyone benefits from the dams and infrastructure that have been built, often with tax dollars; six states agree that sharing in the burden of system losses is reasonable.

California is the holdout, proposing instead its own modeling framework, which recommended a combination of voluntary and priority-based reductions that could result in 6 million people in Arizona’s metropolitan areas and 10 Native American tribes who rely on water from the Central Arizona Project losing all or most of their Colorado River water supply.

Furthermore, because it does not distribute system losses proportionately, the framework reduces Arizona and Nevada’s water supplies to cover California’s losses.

We have a history of equitable allocation

The “Law of the River” is a series of agreements, laws and court cases that governs how waters of the Colorado River are shared and managed.

In 1921, fearing that California would use all the water first, the seven basin states met “to enter into an agreement of the equitable division and apportionment of the water supply of the Colorado River.”

These meetings resulted in the Colorado River Compact of 1922, which divided the basin into an Upper and Lower Division and established a framework to equitably divide the waters of the Colorado River between the states.

Despite deadline:Sens. Sinema, Kelly upbeat about water solutions

In the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928, Congress built upon that framework and equitably allocated between Arizona, California and Nevada the Lower Basin’s portion of water from the mainstem of the Colorado River.

The act also gave the secretary of the Interior power to allocate water through contracts with the states and end users.

Ruling suggests states share shortage burden

In the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact of 1948, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming followed this framework and equitably apportioned the Upper Basin’s portion of water.

However, they apportioned each states water based on percentages rather than fixed quantities so that shortages and surpluses could be shared proportionately.

To resolve continuing disputes over the right to use Colorado River water, Arizona filed suit against California in 1952, which resulted in a decade of litigation in the United States Supreme Court.

Special Master Simon H. Rifkind’s recommendations in Arizona v. California bear repeating today.

The court-appointed judge determined that in the Boulder Canyon Project Act, “Congress did not intend that principles of priority of appropriation should apply in times of short supply to control the interstate allocation of mainstream water.”

Moreover, Special Master Rifkind concluded, “in the event of insufficient mainstream water,” the allocation scheme set forth in the contracts between the secretary of the Interior, Arizona, Nevada, and water users in California “requires each state to share the burden of the shortage ratably.”

Central Arizona Project can't bear this alone

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court justices declined to decide the issue in Arizona v. California and left it to the discretion of the secretary of the Interior.

After failing to convince the Special Master to follow a strict priority system, however, California blocked approval to construct the Central Arizona Project until Arizona agreed in the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968 that the project’s new uses would be junior in priority to California’s in times of shortage.

Arizona agreed to take the largest reductions in the Drought Contingency Plan of 2019.

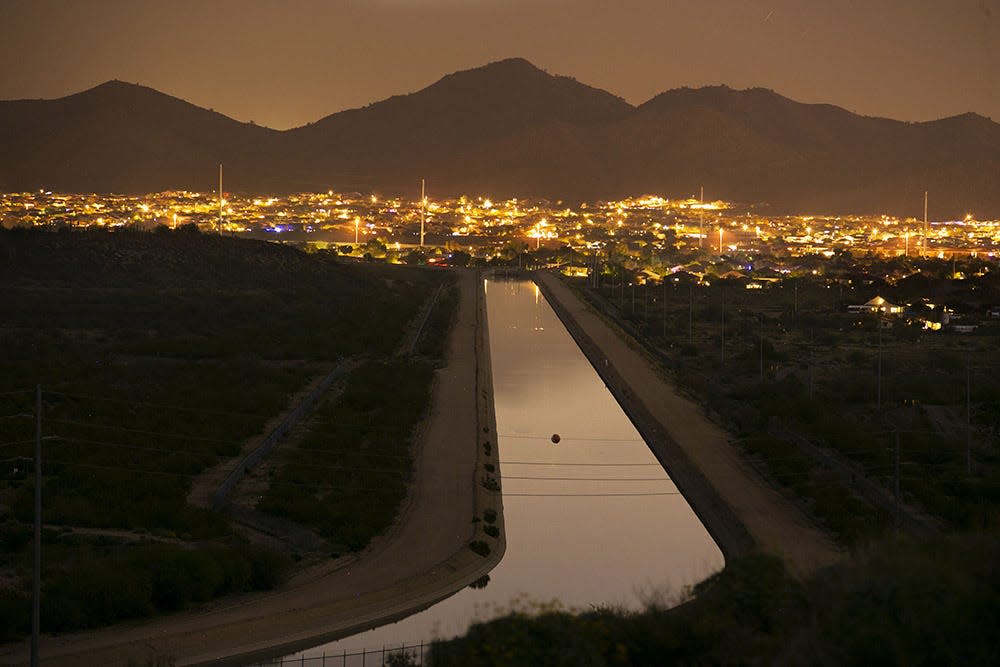

In 2023, Central Arizona Project’s supply is being reduced by 35% while California’s supply is not being reduced at all. Arizonans cannot cover California’s system losses too.

We have run out of time to argue; system losses must be shared proportionately. It’s just common sense for the common good.

Now is the time to act. The fate of the mighty Colorado River hangs in the balance.

Alexandra Arboleda is an attorney with TSL Law Group and vice president of the Central Arizona Water Conservation District board. Reach her at aarboleda@cap-az.com.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Colorado River cuts must be fair. They cannot all fall on Arizona