One student and one typewriter: How two women with a vision founded Johnson & Wales

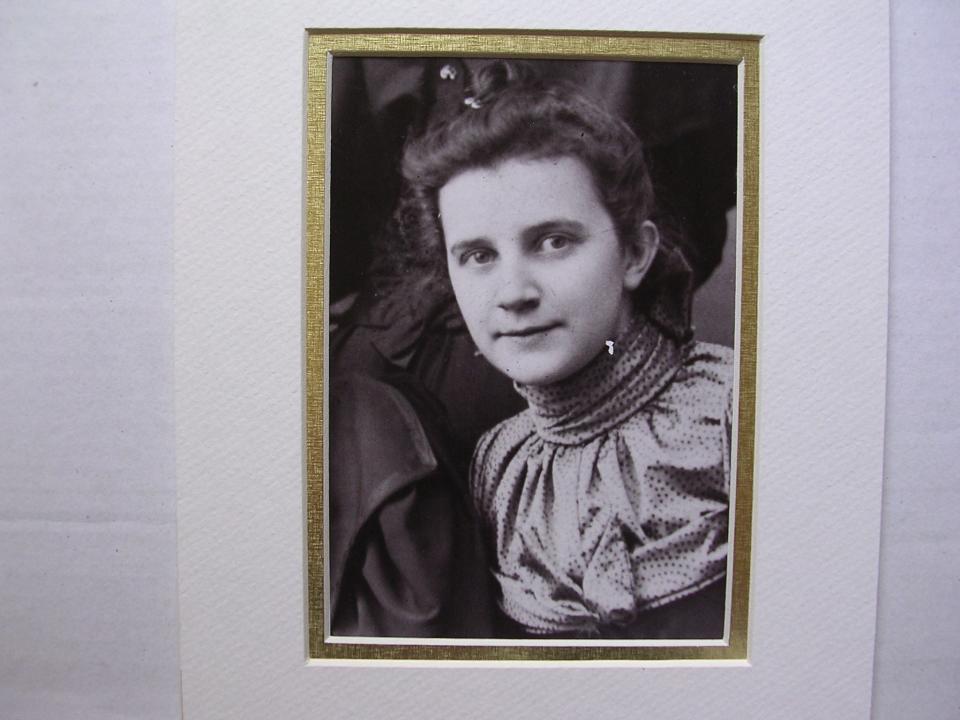

PROVIDENCE — They were born before women had the right to vote and were relegated to roles as domestics, cooks and factory workers until inevitably settling into married life. Even so, Gertrude I. Johnson and Mary T. Wales envisioned a world in which women held positions as skilled typists, stenographers, and bookkeepers with a measure of responsibility and independence.

Johnson and Wales were working as teachers at Rhode Island Commercial School when they conceived of the school that grew to become Johnson & Wales University, a career-focused institution with a global footprint that today turns out fine chefs, business leaders, and hoteliers.

“For 90 years, all anyone knew of the founders was that they started the school in 1914 with one student and one typewriter,” said Marian Gagnon, a Johnson & Wales professor and filmmaker who documented the women’s journey in "HERstory: The Founding Mothers of Johnson & Wales University." “I wanted to tell their story before it was lost forever.”

Stone and Steeple: How a nonprofit plans to turn St. Patrick's Church into affordable housing

The path to partnership for Gertrude Johnson and Mary Wales

Though Johnson and Wales left an indelible mark on Rhode Island, the United States and legions of graduates worldwide, the historical record of their accomplishments is sparse, so thin there is barely a trace in the experiential school’s own archives.

What is known about the two leading ladies — Gertrude Irene Johnson and Mary Tiffany Wales — is that their paths crossed as teenagers at Pennsylvania State Normal School, a teaching school in rural Millersville.

Wales went on to teach for five years in Pennsylvania, fell in love and became engaged to a man who died in the Spanish-American War, according to Gagnon, whose passion is resurrecting forgotten women’s stories. Wales then moved to Massachusetts to resume teaching elementary school.

For her part, Johnson taught briefly before becoming an examiner at a bank, a position that instilled the importance of clerical and accounting work.

Wales and Johnson intersected again in 1913, when both were hired as teachers at Rhode Island Commercial School, a precursor to Bryant University.

It was one year later that the women launched their own school at Johnson’s home at 250 Hope St. with a single student and a typewriter.

They embraced a vision articulated by Wales as a young college graduate: "We should teach a thing not for its own sake, but as preparation for what lies beyond."

While Wales carved out a calming, quiet presence, Johnson cultivated a reputation as a brusque disciplinarian and fearless go-getter. Together they made an “almost magical partnership,” observers said.

“Well, these two relied on each other, absolutely,” the late Vilma Triangolo said in Gagnon’s film. “And one never did anything without asking the opinion of the other. They got along very well, very well.”

Both were known for their principled, businesslike demeanor and for demanding absolute perfection of their charges.

World War I opened up opportunities for women

“EVERY WOMAN should know business methods; private instruction, banking, bookkeeping, shorthand, English, penmanship. MISSES JOHNSON WALES” read an advertisement in the Evening Bulletin Feb. 15, 1915.

World War I had opened up opportunities for women to take on office work and other clerical positions. Johnson handled the administrative duties for the school while Wales focused more on teaching.

Providence had emerged as a major manufacturing and transportation hub, with increasing numbers of women entering college after the Civil War, according to Catherine DeCesare, a history professor at the University of Rhode Island. The women’s suffrage movement was taking foot.

“We start to see this progression moving forward in the beginning of the 20th century,” DeCesare said.

Johnson and Wales saw an opportunity for women, particularly single women, to develop skills.

“They had the vision. They took advantage of the vision,” DeCesare said.

Men had traditionally held jobs as “clerks,” positions that represented a means to advance in an enterprise, she said. But as women began to flood the workforce, those jobs became “feminized” and no longer attractive to men, with lower pay and little room to progress, she said.

Are the feds coming for coffee milk? They might not even find it on the menu in schools.

Memories of 'Miss Johnson's school'

Julia Harring recounted her time at the business school in “Johnson & Wales: A Dream that Became a University,” a book commemorating the university. Interviewed at age 94 in 1996, Harring recalled working at the American Screw Co. in 1918, when her supervisor recognized her abilities and recommended that she enroll at Johnson & Wales Business School.

She took secretarial and accounting classes, focusing on developing financial skills at “Miss Johnson’s school.”

“She was a beautiful teacher who really taught us what we needed to know to get a good job,” Harring recalled in the book. At the time, wealthy girls typically attended college; Harring had to leave high school in ninth grade to help her family during the war.

“There were a handful of girls from Brown [Pembroke College] who would come downtown to take some of Miss Johnson’s classes. They would come in all giddy, talking about what parties they went to the night before, and Miss Johnson would calm them right down,” she said.

Harring also spoke of Johnson’s generosity. Her parents didn’t have much money, so Johnson agreed to waive tuition until Harring graduated and secured a good-paying job.

Harring landed a position at Merchant’s Cold Storage and Warehouse Co. in Providence, the largest cold storage plant in New England outside of Boston.

“I had such terrific training, my boss Mr. Mason at Cold Storage often called Miss Johnson to thank her for teaching me so well,” Harring told the authors.

Ed Cooley's greatest victory: Overcoming a childhood of poverty in South Providence

Obstacles to overcome: Depression, World War II, Hurricane of 1938

The school weathered World War I, the stock market plunge and Depression, World War II and even the Hurricane of 1938.

“Things were topsy-turvy in all lines of work. As we lived through two world wars and a hurricane, we began to feel indestructible …That is said in thankfulness and humility," Johnson wrote to a friend.

Wales and Johnson — referred to by some as “GI” Johnson — recruited Triangolo to enlist students. She spent weekends knocking on doors.

“I never left,” she told Gagnon.

Through the years, Triangolo became a trusted personal assistant to the two women, acting as their companion when they traveled on vacation, according to her 2014 obituary.

As the school grew, it moved to 222 Olney St. and later to larger quarters on Exchange Place downtown and eventually to the Gardner Building at 40 Fountain St. After World War II, more men began to attend.

A blow struck the partnership when Wales was diagnosed with cancer, a weight that Triangolo observed seemed almost too much for Johnson to bear.

Still, Wales would accompany Johnson to work each day, sitting behind a screen in the office until it was time to go home, Triangolo told Gagnon.

Changing of the guard at JWU

In 1947, Johnson and Wales, by then in their 70s, retired to their cottage in Governor Francis Farms at 86 St. George Court in Warwick. They sold their business school, which by then had some 120 students enrolled, to two Navy veterans, Edward Triangolo and Morris Gaebe.

Vilma had married Triangolo, a civil engineer, in 1941. The Triangolos joined forces with their friends Morris and Audrey Gaebe.

Wales died in 1952 at age 78, leaving Johnson despondent. Her obituary notice in the Bulletin was a mere paragraph.

“Miss Johnson took it awfully hard, awfully hard,” Triangolo said.

Johnson returned to Pennsylvania, where she died in 1961 at age 85.

A living legacy

Triangolo and Gaebe expanded Johnson & Wales in the decades that followed, broadening the curriculum and awarding four-year college degrees. They branched into the area of culinary training, an expertise that remains a strong suit today.

Today, it is an accredited institution with 8,100-plus graduate, undergraduate and online students at its campuses in Providence and Charlotte and alumni in 128 countries worldwide. It offers degrees in the arts and sciences, business, engineering, food innovation, hospitality, nutrition, health and wellness, as well as culinary arts, dietetics and design.

“The legacy of our founders, Miss Gertrude Johnson and Miss Mary Wales, lives on in the work of our students, faculty and staff who continue to be inspired by these two trail-blazing women,” said Marie Bernardo-Sousa, LP.D., president of the Providence campus of Johnson & Wales University. “They would be amazed and proud of how far the university has come since it started with one student and one typewriter at a time when women did not have the right to vote.”

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Johnson & Wales in RI founded by two women who broke gender barriers