One of Wilmington's most iconic artists still influential 75 years after her death

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

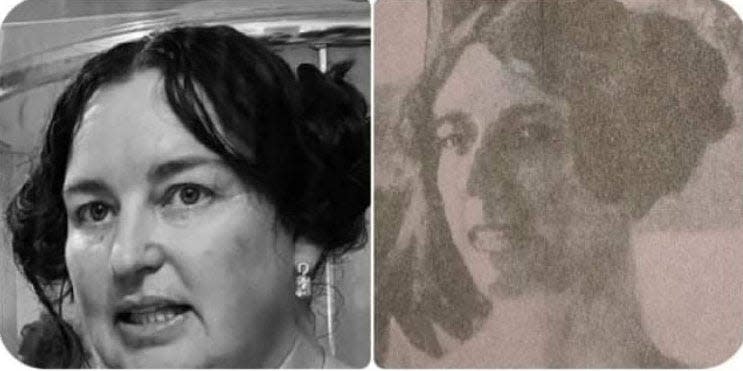

Angela Johnson didn't know she had a famous relative.

An artist who lives in Auckland, New Zealand, Johnson was going through a box of her mother's old family photos during the pandemic when she experienced the shock of recognition.

"Who are these people?" Johnson asked herself, looking through a stack of old black-and-white prints. "One of the ladies looked like my mother, 100 years ago."

And down the rabbit hole she went. After a bit of digging on the internet and some calls to relatives in the United Kingdom, Johnson, who'd thought she was the only artist in her family, dug up a connection to someone she considers a kindred spirit: a painter named Elisabeth Augusta Chant.

George and Harriet Chant of England were Elisabeth Chant's grandparents as well as Johnson's great-great-great-grandparents, making the two artists first cousins, three times removed.

"It's only because I'm an artist myself that I was interested," Johnson said.

But the more she investigated Chant's stunning work and her equally extraordinary life — which took Chant from sailing around the world as a child with her English sea merchant father to becoming an integral part of the artistic community in Minneapolis to, finally, settling on Wilmington's Cottage Lane in 1922 after leaving a mental institution her family had committed her to — the more interested Johnson got.

But, then again, who wouldn't be interested in such a compelling story?

A mythical Port City figure

Chant has long been known as one of Wilmington's seminal artistic figures, one who continues to loom large over the Port City and its cultural institutions nearly 75 years after her death on Sept. 21, 1947.

Wilmington's Cameron Art Museum, which has more than 100 of Chant's paintings as well as some of her personal effects in its collection, is celebrating the 60th anniversary of its founding this fall. Chant and her work will no doubt be part of that. But, three-quarters of a century after her death is perhaps a good time to take another look at Chant's fascinating and deeply influential legacy.

"It's always good to revisit the first Druid to ever come to town," said Anne Brennan, executive director of the Cameron Art Museum and perhaps the leading expert on Chant's life and work.

When she first started working in downtown Wilmington at St. John's Museum of Art (the predecessor to the Cameron Museum) as its curator and registrar in 1990, Brennan said she immediately set out to learn about the museum's collection, of which Chant's works and possessions made up a considerable portion.

The museum has the artist's handwritten journals, textiles and silk brocades she collected, and the trunk where she stored her belongings and work.

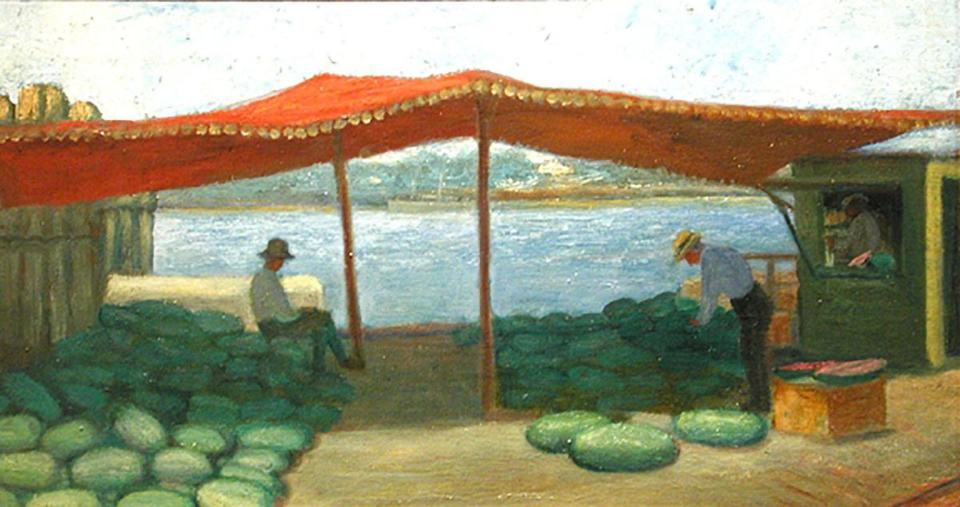

There are also watercolors, drawings and oil paintings, some of them landscapes of the American Midwest of Chant's youth, while others depict the coast of her newfound Wilmington home, where she would start her life over at the age of 57.

Other oil paintings depict figures from one of Chant's lifelong obsessions: the legends and characters surrounding King Arthur and his knights, whose exploits are said to have occurred in the area near the town of Yeovil in England's South Somerset district, where Chant lived as a child before her family emigrated to rural Minnesota in the 1870s, later settling in Minneapolis.

Chant liked to imagine that she was perhaps descended from King Arthur or one of his famous subjects. Brennan said that notion isn't as farfetched as it might sound, given that Cadbury Castle, believed by some to be the site of the mythical Camelot, is just 10 miles from Yeovil, where Chant would return to visit and live for a time as a young woman.

Given these rather mystical obsessions, the connection across the decades to her similarly artistic cousin in New Zealand would've likely been appealing to Chant.

She found success on the burgeoning art scene of Minneapolis in the 1880s, but became a nurse because her stepmother didn't approve of her being an artist. After the death of her father and her best friend two months apart in 1908, Chant moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, where she also became a prominent figure on the local art scene.

In 1917, Chant's siblings had her arrested and involuntarily committed to an asylum in rural Minnesota, where she would spend three years. In a 1993 catalogue accompanying an exhibit of Chant's work at St. John's, Brennan wrote that Chant could've suffered a mental breakdown in the years after the death of her father and friend. Or, her family might've been "increasingly wearied, worried and embarrassed by her constant talk of King Arthur, Druid tors and the reincarnated gods of ancient Egypt."

Once she got out of the asylum, Chant cut off contact with her family and moved away from Minnesota, never to return.

In 1922, seeking a mild climate where she hoped to start an art colony, Chant landed in Wilmington, and a new life began.

Wilmington years

From the start, "Wilmington didn't know quite what to make of her," Brennan said. "She was so eccentric! She wore her hair in braids and she made her own clothes," long flowing fabrics often with medieval or Oriental designs.

So the story goes, Brennan said, when her curious and ultra-religious Wilmington neighbors asked her what church she attended, Chant would respond, "I'm a Druid," invoking the ancient religion of medieval Britain.

Rather than being shunned, however, Chant was embraced. Despite having little to no money, and "being quite 'other' in every way you might think of," Brennan said, Chant was taken care of, and regularly dined with some of the town's wealthier citizens, some of whose children she would teach art.

She settled in the Williams Cottage on Cottage Lane, an 1845 structure that still exists, and she had a studio and taught in another still-existing structure behind it, the Hart Wine House.

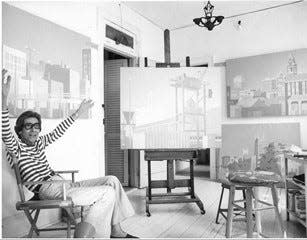

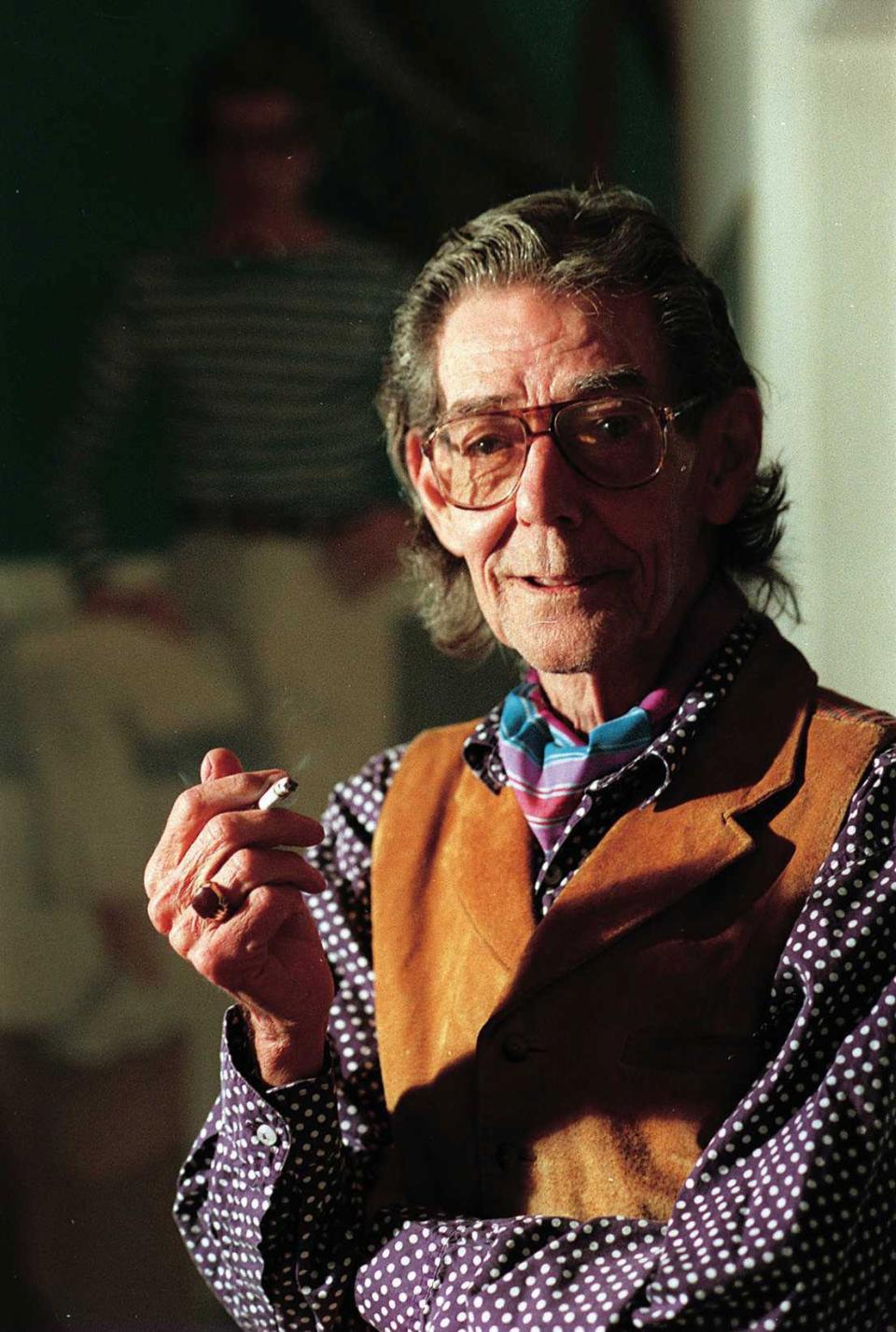

Perhaps her most famous student was the late Wilmington artist Claude Howell, who lived in the nearby Carolina Apartments and took classes with Chant as a teenager and a young man in the early to mid 1930s.

In a 1995 documentary on Howell for North Carolina Public Television, " A Quality of Light," Howell said that he "studied with Miss Chant for years, and she certainly was the biggest influence of my youth … She was a wonderful teacher. A real taskmaster."

Howell described her as a "lady of mystery" who never talked about her past, and this made her "the most fascinating woman."

Physically, Howell said, "She was absolutely hideous. She was so ugly. She had long, chestnut-brown braids which she wore in enormous plaits over each ear."

When a student did a particularly good sketch or drawing, their prize would be for Chant to take out "innumerable hair pins" so that her hair would touch the floor. "That was the only prize we ever got."

In addition to becoming one of Wilmington's most famous artists, Howell would also help establish the art department at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, then called Wilmington College.

From Chant, Howell and others got an education that was both technical (how to mix paint or do perspective) and worldly (lessons in cultures from around the globe that Chant had seen in her travels). She would serve students rice in Japanese-style bowls, wrote the late Wilmington artist Henry Jay MacMillan in the pamphlet "Violet and Gold: The Story of Artistic Activity on Cottage Lane in Wilmington."

MacMillan, who corresponded with Chant when he traveled and kept many of his teacher's letters, would go on to co-found The Lower Cape Fear Historical Society, which still exists. It has many of Chant's writings, some of them done in colored pencil "based on auras that she could see," Brennan said. Others were composed in rune-like, "cryptic writing that no one has been able to decipher."

Brennan noted that Chant was "one of the first Wilmington writers to talk about historic preservation. Writing letters to the editor in the 1930s" on the importance of saving historic buildings, a point of view that certainly found its way to the ears of MacMillan and other early preservationists.

Peggy Hall was a colleague of Chant's (a fellow artist and art teacher) who at her urging, and with some of Chan'ts connections, opened the Wilmington Museum of Art on Princess Street in 1938 with an exhibit featuring works by such artists as John Singer Sargent and Winslow Homer. That museum would close during World War II, but another Chant student, the artist Hester Donnelly, would go on to help start St. John's Museum of Art downtown, which would of course grow into the Cameron.

Brennan said that, in her students, Chant "awakened what was already here and cultivated the people who became our leading arts patrons, activists and artists."

Initially, Brennan said, Chant came to Wilmington with the intention of establishing an artists' colony, "But what she ultimately did here was so much more important."

In his pamphlet, MacMillan recalls that Chant lost her Cottage Lane house and studio when its owner moved back to Wilmington from Boston and decided to live there. Chant went to stay in a room in the Latimer House "and lived there for several years with failing mental equipment, often retreating into her spiritual world and fantasies," MacMillan wrote.

Brennan said that an entry from one of Chant's journals around that time reads, "Painted King Arthur from life at 4 a.m."

When she could no longer live on her own, MacMillan writes, Chant moved to the Catherine Kennedy Home, a facility for the elderly that was then located at 10th and Princess streets. (The home was later expanded and moved to Third Street between Orange and Ann, where it is now the First Presbyterian Church Preschool.)

When Chant died in 1947, the Walker family arranged for her to be buried in the Walker lot at Oakdale Cemetery. There, her tombstone misspells her first name (with a "z" instead of an "s") and misstates her age when she died. (She was 82, not 85.)

Later, Chant's students would return to Cottage Lane in the 1950s and '60s for outdoor art shows during the Azalea Festival. The Azalea Festival art shows, coordinated by the Wilmington Art Association, continue to this day, albeit a couple of blocks away at the Hannah Block Historic USO/Community Arts Center.

In 2012, for its 50th anniversary celebration, the Cameron Art Museum recreated Chant's studio for an exhibit there, using the artist's work and possessions.

All of this is just scratching the surface about the life and work of Elisabeth Augusta Chant, about whom "we have so much more to learn," Brennan said.

One person dedicated to learning more is Johnson, Chant's cousin, who contacted Brennan at the art museum during the course of researching her famous relative.

Johnson said that when she talked to Brennan on the phone, "She asked me, 'Do you have long, brown, auburn hair like hers?'"

Johnson said that she did.

Contact John Staton at 910-343-2343 or John.Staton@StarNewsOnline.com.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Wilmington artist Elisabeth Chant influential 75 years after death