Ongoing ballot counts put focus on USA's disjointed voting system

Heading into Wednesday's marathon absentee ballot count, one of every 10 Wisconsin and North Carolina jurisdictions were scanning absentee ballots on equipment so old it is no longer manufactured. And Georgia was tabulating ballots on a new system marred when electronic poll books failed to check in voters in some counties.

America's aging election equipment didn't appear to be a major, nationwide factor at the polls Tuesday. Nor did brand-new replacement equipment, which states like Georgia rolled out in a historic presidential contest.

"For a system like a roller coaster built on wood with the expectation of high-speed cars driving on it, things went pretty good," said Gregory Miller, co-founder and chief operating officer of the OSET Institute, an election technology research nonprofit. "Nobody got ejected."

Yet because there's no way to publicly document election system problems nationwide, no one really knows how widespread election day machine failures were, or whether small stumbles were part of a bigger pattern.

Issues at one or two precincts can be shrugged off as glitches even as similar problems might occur in other counties. Election officials – and voters – can be left in the dark.

An influx of $400 million in federal coronavirus relief money earlier this year helped pay to replace aging systems. But it fell far short of an estimated $3.4 billion needed for managing elections in the middle of a pandemic. And even new systems come with their own challenges.

Take e-poll books, electronic tablets precinct poll workers use to check in registered voters in place of written voter rolls.

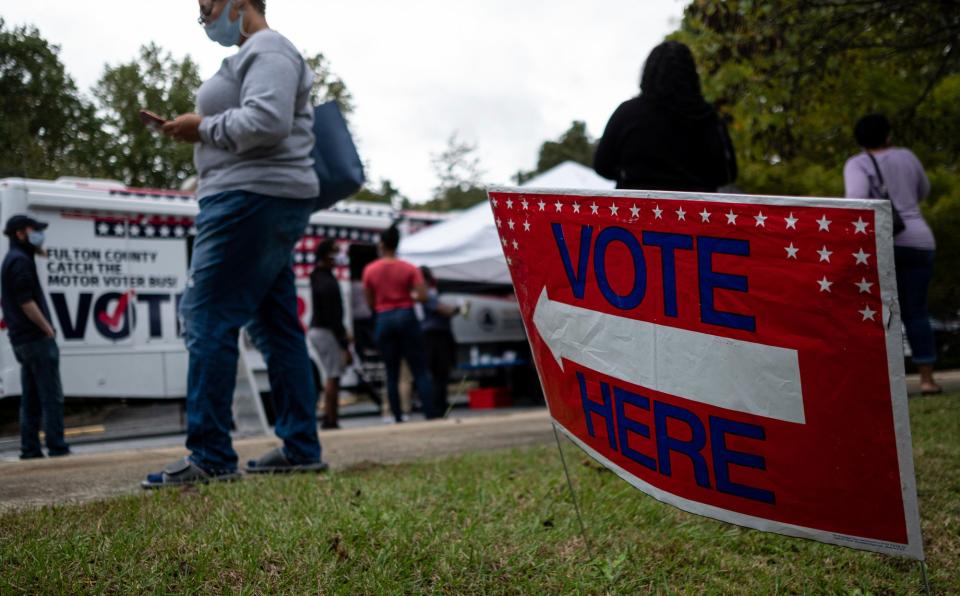

Spalding County, Georgia, made headlines when its e-poll books didn't work Tuesday morning. Morgan and DeKalb counties, also in Georgia, reported problems with the same type of e-poll books. The books were fixed, and a federal judge ordered DeKalb and Spalding to keep the doors open longer to make up for the time voters could not cast ballots.

Far from Georgia, reports of e-poll book problems surfaced in Franklin County, Ohio; Christian County, Missouri; and three Texas counties. Most were fixed quickly. All used the same Missouri vendor, KNOWiNK. So do hundreds of other jurisdictions from North Dakota to Utah, according to data gathered by Verified Voting, a nonprofit advocacy group tracking election systems.

Will your ballot be safe?: Computer experts sound warnings on America's voting machines

KNOWiNK did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

"There is no question that (a national database) would be helpful to election officials," said Lawrence Norden, director of the Brennan Center for Justice's Election Reform Program.

A decade ago, Nordan wrote a Brennan Center report detailing how such a database would have helped identify repeated machine failures. Not only could it guide purchases, Norden said, it could also help local election officials better understand the equipment they are using.

For instance, nothing indicates that an older model of optical scanner being used to count absentees in Wisconsin created problems there. But reports of trouble have surfaced elsewhere.

Norden's study reported that in 2002 in Florida, the same model read 2,642 Democratic and Republican votes as all Republican votes. A small Iowa contest in 2006 reported switched votes. An Arizona county in 2008 reported numbers for five polling places were inflated in a presidential primary between John McCain and Mitt Romney.

Multiple companies selling election systems frequently maintain, troubleshoot and investigate problems in the same systems, points out Susan Greenhalgh, senior adviser on election security for the nonprofit advocacy group Free Speech For People.

Without better information, "election officials just take the vendors’ word on the failure," she said. Election workers and voters have frequently been blamed for missteps.

But just as open-source software can lead to improved security, election system vendors could also benefit from a public airing of issues in a national database, Norden said.

Voter fraud: We analyzed a catalog of absentee ballot fraud: It's not a 2020 election threat

"It would give them an opportunity to be able to explain how they have improved or addressed the problems," he said.

Another concern: Any confusion caused by voting machines can invite legal challenges, especially in close races.

On the other hand, clarity about problems could go a long way toward quashing conspiracy theories before they get started, Miller said, such as Wednesday's viral claim that felt-tip pens could not be read by Arizona vote tabulators.

Hours after the rumor surfaced, election officials were still trying to bat down unsubstantiated “Sharpiegate” claims. Said Miller: "Transparency leads to trust."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Ongoing ballot counts put focus on USA's disjointed voting system