Is online school program backed by Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg the answer for coronavirus closures?

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

Logan Dubin is good with computers. The 14-year-old speeds ahead when asked to use them to complete assignments. He finds it easy to teach himself with online content as his guide. He breezily navigates the internet and educational platforms his school uses. But he doesn’t like it.

“I just don’t like doing work on an online platform,” said Logan, an eighth grader at Rhodes Junior High in Mesa, Arizona. “It’s better to have a teacher guiding you.”

Logan is part of a generation of “digital natives” who were raised on screens. Many schools embrace technology in the classroom as a route to these students’ hearts.

Logan’s feelings about online learning are common. Surveys and interviews find that many students prefer learning directly from teachers and get tired of looking at screens.

Before school closures during the coronavirus pandemic forced districts nationwide to consider online learning, Logan’s school embraced the idea of spending at least part of every day on a computer last year.

What reopened schools will look like:Scheduled days home, more online learning, lots of hand-washing

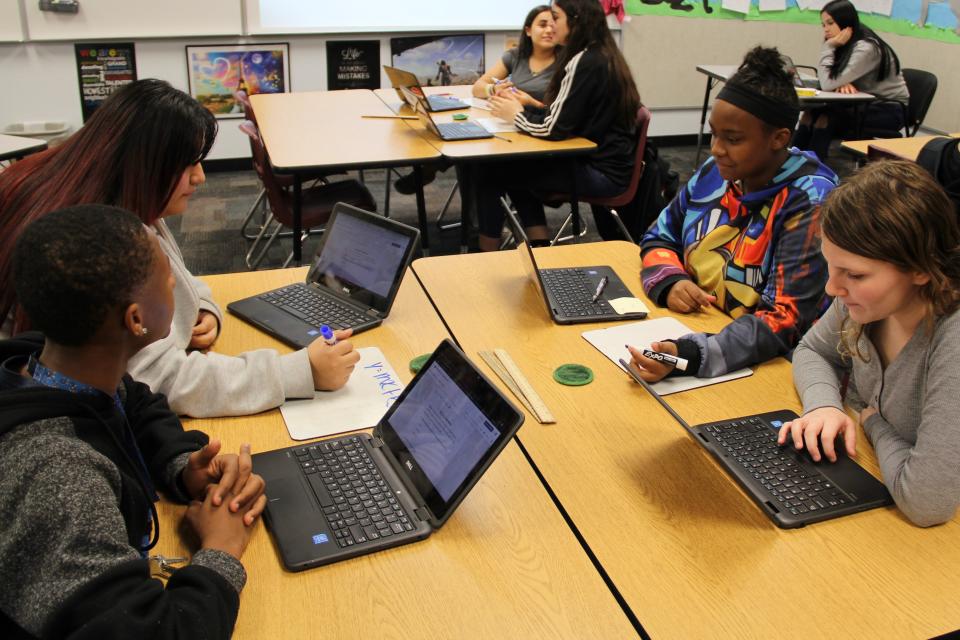

The school uses a platform called Summit Learning as part of an initiative to tailor academic and social-emotional support to students' needs. Teachers achieve that personalized approach on a schoolwide scale by using online learning materials created by Summit and following its model of making time for mentoring and independent learning during the school day.

Personalized learning is one of the most popular goals in schools. It’s also one of the more controversial, as the computer programs can stoke anxieties about student data being hacked, sold or otherwise abused. The computers themselves bring concerns about the negative effects of screens on children’s learning and brain development.

Although computers are the heart of Summit’s model, they’re designed to play a supporting role in teaching kids, not take center stage. The Hechinger Report spent a year exploring the elements of the Summit model, the extensive training process for schools that are new to the program and the twists and turns of implementation. That academic content is neatly packaged online in the Summit Learning Platform, but that’s not what eases the transition to remote learning for schools. Summit’s greatest strengths lie offline.

A network of charter schools in California and Washington developed the Summit Learning Program for their students almost a decade ago; the model got a boost in 2014 from Facebook engineers after Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, visited a Summit middle school. Free help from the engineers beefed up the platform and spurred Summit Learning’s move into more schools around the country.

Since 2016, when the couple launched an LLC to coordinate much of their charitable giving, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative has committed $142.1 million in grant support for the Summit Learning Program. Nearly 400 schools use it across 40 states. (The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative is one of many funders of The Hechinger Report.)

The online platform includes a project-based curriculum for science, social studies, math and English language arts for students in grades 4-12, along with additional content in those subjects that students can tackle at their own pace. It has teaching tips and resources, progress-tracking capabilities and guides for mentoring.

Fears about data privacy and screen time, along with concerns about Silicon Valley’s conflicting interests as it pushes into public schools, have hurt Summit’s reputation. There have been highly publicized problems in some districts that adopted the program.

'Historic academic regression': Why home-schooling is so hard amid school closures

A spinoff organization, TLP Education, separated from the charter school network that developed the Summit Learning Program last year and shifted its focus to helping partner schools and districts use the model. This commitment ensures Summit won’t offer a quick-fix for schools turning to remote instruction because of the coronavirus, but more schools adopt the program every year.

According to TLP Education leaders, 82% of schools using the program last year continued with it this year, and about 50 schools joined their ranks, primarily from districts expanding the model. Because Summit requires schools to spend almost a year preparing to adopt its model, the coronavirus is not likely to cause a surge in the number of Summit schools next fall.

In dozens of interviews, Summit leaders, education researchers and the people who teach and learn in schools that use Summit agreed that the platform offers a systematic way to achieve the otherwise complicated, messy objective of personalizing learning. Observations in classrooms and at Summit’s summer training, which was previously closed to the media, suggest a nuanced picture of a program that can be used poorly but can also transform teaching and learning for the better – and not just because of computers.

United behind Summit Learning

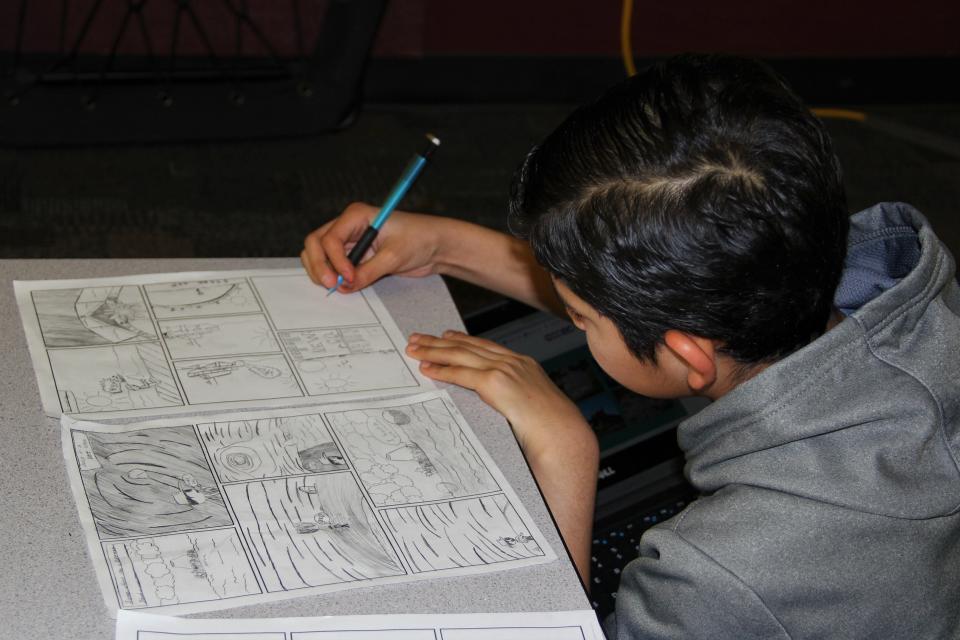

At Rhodes Junior High, where Logan goes to school, students in Allison McIntosh’s seventh grade science classroom were three weeks into a project. They had to draw a comic book story of a geologic site’s past, present and future based on the conditions that build up or chip away at mountains, carve valleys and dry out lakes. Many students had their laptops open but ignored them, looking at McIntosh while she spoke and at sample comic books she placed at their tables.

“How many boxes does it take for a character to move, for something to happen?” McIntosh asked, prompting students to draw lessons from the comic books in front of them. “How do they draw that something is happening?”

Rhodes serves a predominantly low-income population of about 900 kids outside Phoenix. The school’s most recent rating from the Arizona Department of Education is an F because of below-average student growth and achievement.

Two years ago, Principal Patricia Christie lost almost half of her staff – some she invited to leave and others took advantage of an invitation to switch to a different school if they didn’t want to go all-in on personalized learning. The school is perhaps uncommonly united in support of Summit and the broader educational philosophy on which it is based. The parent community at Rhodes is not particularly involved, Christie said, and there hasn’t been the pushback to Summit or online learning that other communities faced.

In Cheshire, Connecticut – a higher-income community with more active parents – the school district scrapped Summit in 2017 because parents didn’t want so much of their children’s educational data to be tracked by an outside company, particularly one backed by Zuckerberg, who critics worry is supporting Summit as another massive data collection engine, like Facebook.

Want to take back your online privacy? 7 easy steps to stop Facebook and others from spying on you

Summit Learning does share student data with 20 different service providers who help facilitate the platform’s capabilities. Facebook has not been one of them since 2017, but the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative has full access to the Summit Learning platform’s content and traffic data. On its website, Summit Learning emphasizes that it will never sell student data or seek to make money from the people using the platform.

In Cheshire, parents bemoaned the quality of content in Summit and the time their kids spent on computers. At Rhodes, Christie doesn’t hear complaints like that. Since 2017, Summit has revised its middle and high school curriculum, and teachers said it’s high-quality.

McIntosh, the science teacher, said she loves having a complete curriculum to work from. She used to spend a lot of time creating her own materials. Now, she finds she has extra time to meet individual kids’ needs.

“I’m not spending as much time on the ground level,” McIntosh said. “I’m getting directly into interventions, targeted materials, resources, lesson plans, pedagogical skills that are tailored toward the kids I have sitting right in front of me.”

‘I need help’: In 6 home classrooms, families try to keep coronavirus learning alive

Hilary Witts, the director of Summit at Aspen Valley Prep Academy Charter School in Fresno, California, said her school’s state test scores jumped by the end of the first year with Summit, in large part because the program helped teachers identify gaps in student understanding and offered targeted support to help them catch up.

By the third year, the school surpassed the state average and nearly doubled the district’s percentage of students meeting or exceeding standards on eighth grade reading and seventh grade math.

At Wellington High School in Kansas, administrators expected Summit to boost, in particular, sophomore performance on state reading tests. Stephanie Smith, the assistant principal, said the curriculum’s interdisciplinary focus and emphasis on argumentative writing, textual analysis and inquiry seemed like it would have to have an impact.

After one year, student performance improved, and for the first time in more than a decade, sophomores from Wellington performed above the state average, Smith said.

“We were absolutely elated to see the data on that,” Smith said.

‘A mindset shift’

Though one of the biggest criticisms of Summit is that it turns teaching over to computers, many educators who use it said they’re doing more intensive teaching than ever. When Angela Pipinich, a math teacher at Rocky Mountain Middle School in Idaho Falls, talks about Summit’s impact, she doesn’t even mention computers. She said her classroom is much more student-led.

“I think a huge misconception is that Summit Learning is a computer program,” she said. “It’s a mindset shift.”

Summit’s math curriculum is designed to occur almost entirely off-screen, according to Andrew Goldin, executive director of TLP Education. Its science, English and social studies curricula are project-based, so students are meant to spend a significant chunk of time collaborating.

Teachers like the way Summit’s model prioritizes stress management and relationship skills, independence and students’ belief in their ability to learn.

The model suggests students receive 10 minutes per week of one-on-one time with a mentor. Teachers said the time leads to better relationships with their students. Administrators said it changes the feel of schools. And students love it. Even those who said they don’t like learning on computers through Summit don’t write off the program entirely because of this component.

Schools and coronavirus: Parents fear for their children's mental health amid coronavirus pandemic

Those mentoring relationships have been a lifeline for Rhodes since the school closed in mid-March because of the coronavirus. Students found their mentors to be obvious points of contact online or by phone; because of those connections, school leaders have a better understanding of students’ needs.

Despite the emphasis on the off-screen elements of Summit’s model, computers hold the content that drives instruction, and they provide a place for student-teacher communication.

Students take quizzes and tests through the platform, submit assignments online and track their progress in each course. They set academic goals and prepare for meetings with their mentors through the platform.

For nearly half of Rhodes students, that was put on hold when the district closed March 16. It wasn’t until mid-April that the school hosted its first device pickup event, giving students a chance to check out computers they normally use in class. Christie estimated that about 20% of her students didn’t have devices by the end of April, when the district began asking schools to prepare 90 minutes of activities per week for kids in English, math, science and social studies.

Half of US lacks broadband access: Coronavirus for kids without internet means quarantined worksheets, learning in parking lots

Some students picked up where they left off in the Summit Learning Platform; many others made limited progress under the new educational reality, though Christie maintained that using Summit and having more flexible, personalized learning processes in place gave the school a leg up.

When schools are open, the Summit model calls for one class period per day of “self-directed learning” time. Students work through readings and instructional videos from the web at their own pace, taking assessments as they prove they are keeping up with the material.

Students have to pass quizzes and tests with a score of at least 80% or retake them. Teachers decide how many times a student can retake an assessment before intervention is needed. When students struggle to pass the quizzes more than twice, teachers pull them for small-group workshops to supplement the online instruction.

When screen time is productive, researchers tend to agree that it is not, in itself, bad, at least for older kids. That’s Summit's argument.

“All screen time is not the same. There’s nuance,” TLP’s Goldin said. “They are using their computers to collaborate, word process, research – those are skills for the 21st century. Screens are going to be a part of our lives going forward.”

Screen time: Yes, your kids are on screens in these trying times. No, you're not a terrible parent

Teachers find other downsides to Summit. Amethyst Hinton Sainz, an English teacher for students with very limited English fluency at Rhodes, has had a hard time helping her students work through Summit’s text-heavy curriculum.

Although Summit provides translation tools and built-in ideas for making the projects and assignments manageable for kids learning English, Hinton Sainz has spent a good chunk of this year, her first with Summit, revising the curriculum to make it accessible for her students. For those least fluent in English, Hinton Sainz sometimes has to scrap the projects entirely.

Teachers in other schools found the shift to project-based learning to be a massive, unwanted change from traditional instruction. It’s messy and loud, and teachers have to relinquish some of their time at the front of the room. It can take greater expertise to help kids work productively in groups.

In Providence, Rhode Island, a report by researchers at Johns Hopkins University chronicled a dysfunctional school system that has been taken over by the state. A handful of schools in Providence used Summit, but they incorporated the program differently – some teachers stuck to the curriculum, and others used only the self-directed learning content to offer remedial education for students. Some teachers abandoned direct instruction entirely, according to the Johns Hopkins researchers.

Even when Summit is implemented as designed, kids still dislike parts of it.

Kids who are used to easy A’s under the more traditional model can be particularly hard to convert. They face an unfamiliar struggle if hands-on projects demand more active work than listening to lectures and memorizing facts, or if their teachers funnel texts to them that are more challenging than those they would have studied in a whole-class reading.

Thin research base

Personalized learning has become such a popular goal in schools because it is basically a catch-all for some of the most lauded educational ideas of the past century: letting students progress at their own pace; giving them opportunities to learn through in-depth projects; supporting strong adult-child relationships; using data to inform teaching; and developing students’ understanding that, with enough time and effort, they can learn anything.

For a program so steeped in research and so scripted that teachers could teach an entire course without having to come up with a single original idea, it leads to frustratingly varied experiences from one school to the next. That, too, is by design.

Though schools sign a partnership agreement committing to implement all three core elements of the Summit model – projects, self-directed learning and mentoring – teachers and schools ultimately do what they want.

Donna Stone, founder and executive director of New England Basecamp, which has supported 10 schools in Providence using Summit (and almost 30 elsewhere), said daily activities are “gift-wrapped” for teachers. She has seen major differences, mostly based on school conditions such as teacher turnover, staff support and technology access.

Convinced by the logic behind personalized learning, Zuckerberg donated nearly $26 million in 2018 and $43 million in 2019 to Summit Public Schools and TLP Education through the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

Although there is a strong research base behind the elements that make up personalized learning, the research into comprehensive models such as Summit’s is extremely thin. Summit resisted attempts to study whether its model improves learning outcomes and the school experience for the more than 84,000 students who use the program.

Goldin said individual schools track their own data, which cumulatively represents “tons of evidence, case by case, of successes that schools are seeing.” The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, as its biggest funder, is watching for more rigorous research.

Coronavirus-related school closures offered fresh examples of Summit’s potential. Summit was not intended to work as a remote learning solution, but schools that most deeply embraced the model in their buildings found it surprisingly transferable.

Advice for teaching at home: How to home-school during coronavirus quarantine

Nicki Chase, whose daughter is a junior at Classical Academy High School Personalized Learning Campus in Escondido, California, was amazed by the smooth transition.

Chase said her daughter has capitalized on the self-directed learning skills she practiced through Summit for years. Even without direct instruction from teachers, she knew how to start a lesson on her own, take a diagnostic assessment to get a sense of her strengths and weaknesses, click through the learning materials to learn more about the topic, take notes along the way, reach out to peers as a first stop for help and communicate with a teacher through the platform when necessary, Chase said.

Chase’s home has internet access and enough computers to go around, so her daughter has been able to join videoconference sessions with teachers and classmates when they’re offered. Her daughter’s mentor has checked in multiple times to make sure she is on track.

“I’m not worried there’s going to be a gap in her learning,” Chase said. “It’s really amazing as a parent to get to know that that part is covered.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Coronavirus online school: Facebook Mark Zuckerberg's Summit Learning