New online Wolastoqey language dictionary a family affair

A Wolastoqew family in New Brunswick has lent their voices to an online dictionary where viewers can hear over 19,000 words spoken in their language.

The Wolastoqiyik live in western New Brunswick, eastern Quebec and parts of Maine. There are just under 100 fluent speakers of Wolastoqey left, and Roseanne Tremblay Clark, who spent over 30 years in language education, knew she had to help.

"Every time we lost a speaker, it just took a big chunk of my heart," she said.

Tremblay Clark started the project three years ago and spent hundreds of hours researching and speaking to other language speakers, including her nine siblings from Neqotukuk, Tobique First Nation, about 120 kilometres west of Fredericton.

Raymond and Doris Tremblay are the parents of the siblings, and Allan Tremblay credits his mother Doris for only speaking the Wolastoqey language at home. (submitted by Roseanne Tremblay Clark)

"The things we put in were things that we remembered from our parents, our grandparents, our aunts and uncles," she said.

The siblings range from ages 63 up to 77-year-old Allan Tremblay. He held on to his language despite attending federal day school — an experience he and his siblings share.

While separate from the residential school system, federal Indian day schools and federal day schools were also part of a policy aimed at assimilating Indigenous children.

Allan Tremblay said his mother Doris only spoke Wolastoqey at home.

Keeping the language alive is worth the effort, he said.

"It's part of our culture and it's part of us, you know, because if our language dies, I mean we as a people are going to die as well," said Allan Tremblay.

"It just warms my heart when I hear kids trying to use our language."

A learning tool

Tremblay Clark turned to linguist Robert Leavitt to edit the dictionary. Leavitt worked on a Maliseet-Passamaquoddy dictionary published in 2008. (Maliseet is an old term; they are known in their own language as Wolastoqiyik.)

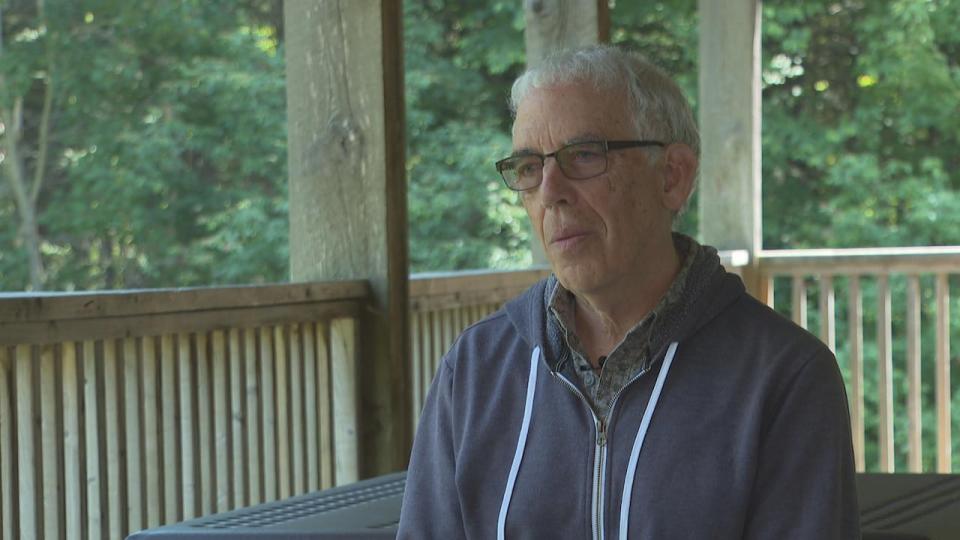

Robert Leavitt is a linguist professor and copy edited the Crow Clan dictionary. (Mrinali Anchan/CBC)

Leavitt said the Maliseet-Passmaquoddy dictionary features primarily Passamaquoddy speakers. The languages are similar, he said, like the difference between Canadian English and British English.

Leavitt said the Crow Clan dictionary features exclusively speakers of Wolastoqey and the dictionary will be a resource to help people to learn and teach the language.

For him, working with the clan was an opportunity to learn more about Wolastoqey culture.

"The way [languages] are structured gives insight into another way of thinking about the physical environment, the geography of the region, the relationships among people and the relationships between people and the environments in which they live and work and raise families," said Leavitt.

Justine Tremblay is Wolastoqey and teaches land based education, she teaches youth the language to connect them to the land and the language. (submitted by Justine Tremblay)

Justine Tremblay, Allan's daughter, works at the Wolastoqey Tribal Council teaching land-based education to youth in five communities. She and other Tremblay family members use the dictionary as a language tool to educate others.

"They created this resource for people like me to continue to learn the language, to learn it confidently and to share that knowledge for the next generation," said Justine.

She said she's glad to have the voices of her family speaking the words online because she said it's easier to learn the language by hearing it.

The Department of Canadian Heritage provided over $90,000 in funding for the online dictionary.