Onward To Mars: What Our Journey To the Red Planet Might Look Like

At 12:50 PM EDT, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, bringing to an end the most ambitious space mission to date. But a question still remains 50 years later—what comes next?

It's the year 2037. A spaceship carrying American astronauts has just embarked on an historic missions to Mars.

Rocket liftoff was perfect and everything is going according to plan. Now the spacecraft nears the moon and prepares to dock at a fuel depot in high lunar orbit. At this space-based truck stop, it tops off its tanks with propellant manufactured from a factory on the lunar surface, and heavy with fuel, takes off again for the long journey to its final destination. Do you believe this scenario? NASA does. And the agency is already engaged in the most audacious project in its history. The goal: turn ambitions of moon-made rocket fuel and a mission to Mars into reality.

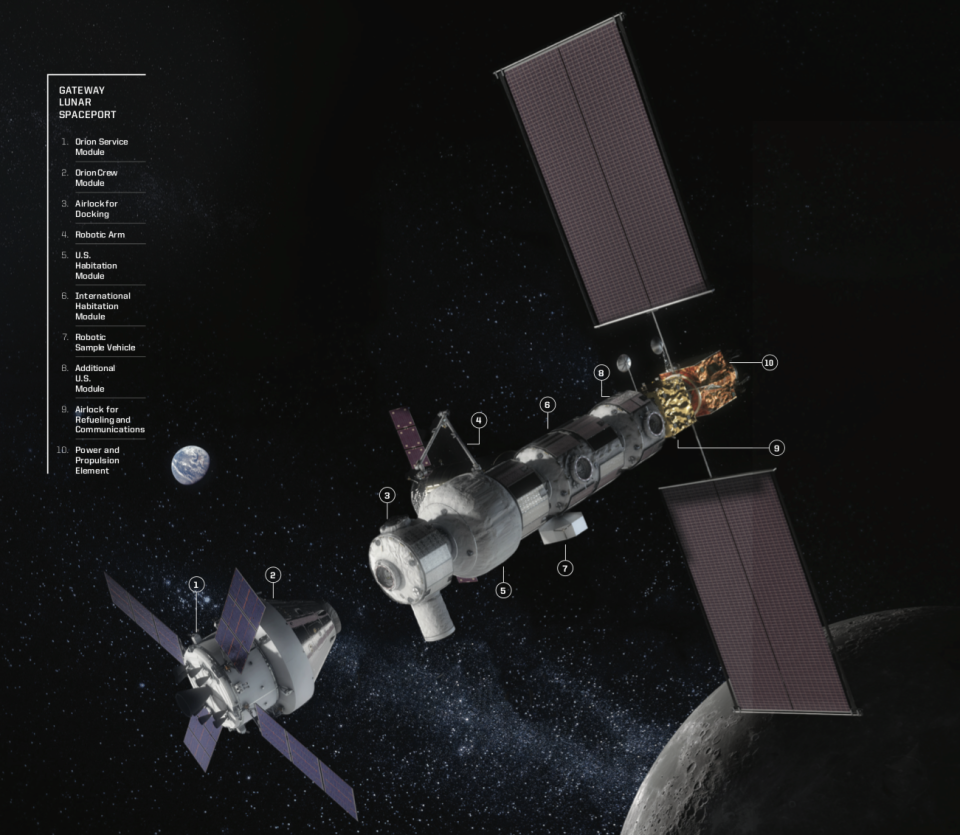

NASA’s Gateway program is the first stepping-stone on a journey that uses the moon to connect humanity to Mars. The new Gateway spacecraft will be a workstation in elliptical orbit around the moon, a remote office that astronauts will access by commuting to and from the moon’s surface. Gateway’s immediate purpose will be to support lunar exploration. But as it grows into a refueling depot and servicing platform, it will become the jumping off point for flights to Mars.

“What Gateway means for us as a society …it expands our concept of home to the lunar vicinity,” says Sean Fuller, NASA’s Director of Human Space Flight Programs and International Partner Manager for the project.

Previously called Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway and then Deep Space Gateway in 2017, the program was originally conceived to aid missions to Mars in the wake of the 2010 cancellation of NASA’s Constellation program, which called for a manned return to the moon by 2020. Rebranded simply Gateway, it is now the hub around which all of NASA’s major plans for human space exploration revolve.

Anyone with an interest in space likely wants to go to Mars. NASA’s current plans for achieving the dream have drawn fierce criticism as a distraction from the ultimate goal. That’s to be expected. But given that the stakes are higher and the competition greater than ever before, it’s critical we understand our national space mission. And get it right.

“Make no mistake about it: We’re in a space race today, just as we were in the 1960s,” Vice President Mike Pence told the National Space Council in March. In a speech crafted to stir a sense of urgency, Pence invoked everything from China’s “ambition to become the world’s preeminent spacefaring nation” to a Biblical certitude that “His hand will guide us” in the government’s effort to rally the space community.

Getting There

Gateway is a cluster of interconnected modules that will orbit 930 to 43,500 miles above the lunar surface. Each module will be dedicated to a primary task or tasks—power and propellant, habitation, logistics and utilization, airlock—but the craft will function as a single integrated vehicle.

NASA will deliver large pieces of Gateway on multiple Space Launch System (SLS) megarockets for assembly in space with autonomous rendezvous and docking technology. It’s scheduled for completion in 2026. Extending the metaphor of “home,” NASA notes that its size (55 cubic meters of habitable space) is similar to a studio apartment, whereas the International Space Station (ISS) is larger than a six-bedroom house. Gateway will house four crew members for missions lasting 30 days or longer.

If Gateway sounds reminiscent of the ISS—which NASA proposes extending or retiring in 2024—it is and it isn’t. While Gateway employs some of the technology developed for ISS, its purpose is fundamentally different. The objective of ISS—which orbits about 250 miles above earth—is research. Gateway is built for exploration.

Check that. Sustainable exploration.

“‘Reusability’ has become the catchword now in near-space activity,” says Jeffrey Hoffman, Ph.D., a professor in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, the first astronaut to log more than 1,000 hours of flight time in the Space Shuttle.

What this means for Gateway is teaming with international and commercial partners to develop and build reusable components. The most critical piece is a reusable lunar landing system that can make multiple trips between Gateway and the moon. In November 2018, NASA announced nine finalists for its Commercial Lunar Payload Services contracts. The companies will compete for design and manufacturing contracts. No plans have been approved, but ambitions are huge, even for NASA.

“For perspective, Apollo was a 15-metric-ton lander with two crew that gave NASA one use for three days (on the moon),” says Fuller. “Gateway will support a 40-metric-ton lander with four crew to go to the lunar surface for a much longer duration.”

Why the Moon? Why Now?

Manned moon landings are worth debating—“Didn’t we do that 50 years ago?”—but NASA sees plenty of reasons to return. That assures Gateway’s preeminence in future planning.

The moon likely holds information about the origins of our solar system. Lacking wind, rivers or plate tectonics, the surface of the moon has likely not changed much since its origin, offering physical evidence to what Earth may have been like during its infancy. Efforts to dig out creation secrets would add the benefit of astronaut training. “It’s been almost 50 years since [humans] have explored the surface of another planetary body,” says Hoffman. “We have to build up that expertise again, and there’s a lot we can learn about exploration in a spacesuit on the moon that we can directly transfer to the exploration of Mars.”

Perhaps the most intriguing piece of the near-term Gateway plan is its connection to what is thought to be large deposits of water ice on the South Pole of the moon. Though no ground sampling has been done to determine its physical state or distribution, such deposits could become the source of fuel for future missions to Mars and beyond. Using space resources to create products such as fuel for human exploration is a process known as in-situ resource utilization, or ISRU. It’s a big part of the reason that when Pence directed NASA to put American boots on the moon by 2024, he also promised, “they will take their first steps on the moon’s South Pole.”

“The lunar South Pole is an area of great interest and it’s not something you can go to very easily directly from Earth,” says Fuller, noting Apollo’s trajectory didn’t give its lander access to the region. “Gateway provides us an opportunity to go to any location on the moon.”

What happens once we get to the lunar South Pole is the subject of even more speculation than Gateway itself. Converting water ice—if indeed abundant reserves are there in extractable form—into rocket propellant will require enormous amounts of energy, in most scenarios imported from Earth at tremendous cost.

“You have to melt the ice, purify the water, filter it out, because you can’t put dirty water into an electrolyzer unit, electrolyze it, take the hydrogen and oxygen and liquefy it, then load it into a rocket and launch it off the surface of the moon to get it to the depot,” says Hoffman. “Developing a real sustainable mining operation in permanently shadowed craters in polar regions of the moon is a very big deal. The surface temperature within those craters is about 40°Kelvin (minus 388°Fahrenheit). A lot of the materials we normally use don’t even function at those temperatures.”

The Naysayers

For NASA and many in the space community, Gateway is a bold and exhilarating endeavor charged with enormous possibilities. To a chorus of detractors, however, it sounds like a government boondoggle.

Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin called Gateway “absurd.” Former NASA Administrator Mike Griffin labeled it “stupid architecture.” Hoffman calls it “premature,” saying “its value becomes apparent only if you get to the point of operating sufficiently frequent flights to and from the surface of the moon with a reusable descent-and-ascent vehicle.” In other words, why build a gas station before you’ve even got a car in the driveway?

“If we really want to get to Mars by way of the moon (a very logical and beneficial approach, in my mind), the Gateway is a huge distraction,” wrote Scott Parazynski, M.D., founder of Fluidity Technologies, veteran of five Space Shuttle missions, and author of The Sky Below, in an email to Popular Mechanics. “Not only will construction of the Gateway station strip vast and critical resources, resulting in basically an ‘ISS 2,’ it will divert attention and precious time in developing a stepping-stone lunar outpost.”

For the time being, NASA is operating as if it can have it all—Gateway, a 2024 lunar landing, and Mars—on a budget that’s about 0.4 percent of federal spending in fiscal year 2020, compared to its peak of 4.5 percent in the mid-1960s. The agency likely has more on its plate than it has funds to support. But there’s an undeniable lift in the step of everyone at NASA these days. A Gateway- assisted moon landing provides a goal many have yearned for since the last Apollo flight in 1972.

“When we go to Mars, we’re going to be there for at least two years,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine testified before the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology in April. “So, we need to learn how to live and work in another world. The moon is the best place to prove those capabilities and technologies. The sooner we can achieve that objective, the sooner we can move on to Mars, and that’s ultimately the objective here.”

NASA has emphatically established its course. What remains to be seen is if it can maintain the trajectory needed to get where it believes it can go.

You Might Also Like