Op-Ed: As Confederate statues fall, build monuments to Black heroes at risk of being forgotten

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On the night of Jan. 8, 1811, a mixed-race man named Charles Deslondes led a group of people in an attack on a plantation owner in lower Louisiana that became the largest uprising of enslaved people in American history, and the first that required the intervention of the U.S. Army.

The attack didn’t go as planned. Deslondes had targeted Manuel Andry, head of the local planters militia, on the assumption that his property would house plentiful weaponry the insurgents could co-opt. But no big cache of guns was discovered, and although Andry’s son was killed, the father somehow got away.

Undaunted, Deslondes and his fellow rebels began a long, nighttime march through Louisiana’s German Coast toward New Orleans, where they hoped to take over the local armory. And along the way, to the sound of rhythmic drumming and chants of “Freedom or death,” their numbers grew rapidly as they attacked other sugar plantations and liberated enslaved people.

Through courage and wile, the rebels managed to resist or elude attacks by white militias, but were finally caught by the Army and local vigilantes in an open field the next morning. They were badly outnumbered and outgunned. Knowing that they would be slaughtered, Deslondes ordered his men into a close line of battle and told them to steel themselves for the final charge, not wasting the scarce ammunition in their old muskets until they could clearly see the faces of the white men galloping toward them on horseback to wipe them out.

This story is unknown to most Americans, but in it we should hear strong echoes of more celebrated national tales involving nearly identical features: the brave “whites of their eyes” tactic, the equivalent of a morale-building fife-and-drum corps, and above all the unquenchable will to freedom.

Deslondes and his men deserve to be honored as some of the greatest heroes of American liberty. Among those who survived that brutal final charge, the tightknit group of co-leaders of this revolt refused to bear witness against one another and betray their cause, for which Deslondes had his arms chopped off and his legs broken and was shot before his body was put on a spit and publicly roasted.

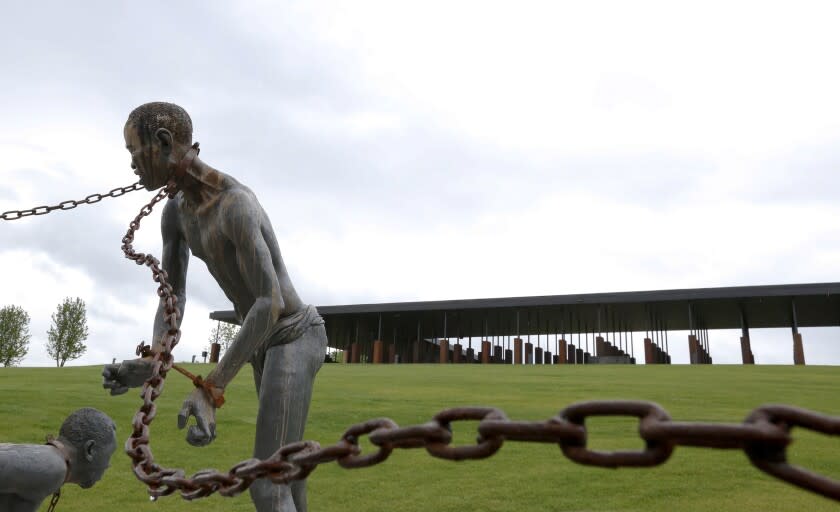

The only monument to the German Coast Uprising that I could find was at the privately owned Whitney Plantation, near the site of these events and badly damaged by Hurricane Ida. There, on a modest plaza, 19 carefully sculpted Black busts perch atop metal spindles, with Deslondes front and center with a plaque bearing his name above the word "Leader."

The scarce public commemoration of Deslondes and his freedom fighters is emblematic of a much larger crisis of memory. Enslaved people brought from Africa and their descendants played a central role in the rise of the United States and of the West in general, and indeed in the winning of their own freedom in the Civil War.

A related injustice is being addressed as governments and institutions remove grotesque monuments to the likes of Robert E. Lee and John C. Calhoun, militant defenders of slavery. But this must be seen as merely the first of two necessary acts. The second is to elevate African American history and heroes to their proper public place, recognizing their role at the very center of American history and their long, lonely struggle to realize this country’s most hallowed ideals.

One should not have to seek out a destination like the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture to encounter this history; monuments to African American individuals and their causes should pepper city streets and the halls of power like Confederate statues once did.

The generally unfamiliar story of Charles Deslondes would be a good place to begin, and there is an embarrassment of other possibilities as well. Black soldiers fought in the American Revolution. Black residents rebelled for their freedom in early New York. And enslaved people played a decisive but largely unrecognized role in the victory of the North in the Civil War.

These are not the fruits of new discovery. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant himself recognized how Black fighters had courageously tipped the balance against the South, at precisely the moment when Northern whites were chafing loudly about the cost to them of fighting for universal freedom. “The problem is solved,” he wrote, as freedmen poured into the Union Army late in the war. “The Negro is a man, a soldier, a hero.”

The call to incorporate African Americans into the heart of our national story, though old, remains stubbornly unfulfilled. One finds expression of its early roots in the correspondence on slavery of Thomas Jefferson and a freeborn Black man named Benjamin Banneker. African Americans carried this call forward in the next century, as when James Forten, Richard Allen and other Philadelphians wrote that “our ancestors (not of choice) were the first successful cultivators of the wilds of America” and their descendants were therefore entitled “to participate in the blessings of her luxuriant soil.”

Roughly a century later, in 1924, the Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois called for recognition that “it was black labor that established the modern world commerce which began first as a commerce in the bodies of the slaves themselves.” In the 1960s, the Black historian Benjamin Quarles wrote that “if in the eyes of the world today the United States stands for man’s right to be free, certainly no group in this country has sounded this viewpoint more consistently than the Negro.”

Restorative messages like these are winning grudging acceptance in our history books. Now it is time for them to be reflected in our parks and other public places as monuments for all to see.

Howard W. French, a professor of journalism at Columbia University, is the author most recently of "Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.