Op-Ed: After my favorite 5th-grader of all time went to prison, chess kept us connected

The letter I received from my former student thanked me for teaching him chess in fifth grade. It was a setup. Now, 11 years later, he was inviting me to play his game of chess — inmates’ chess. He is still my favorite fifth-grader. He was sweet and charismatic then. He offered an update: “Mr. Karrer, when I was fourteen I caught nine attempted murder charges, an arson, and some other charges. So, I’m in prison.”

But I already knew most of that. I had kept an ear on his doings.

He grew up in east Salinas, Calif., in Acosta Plaza, a low-income housing project and an exceedingly dangerous place. The great Latino killing zone for far too many. A few years later he moved to the small tough town where I taught. He’d show up after school, often not attending class that day. He’d have a chessboard set up directly on the other side of my door. I couldn’t get past him.

“Just one game teacher! Come on.”

We’d usually play three. I taught him chess, and he’d cautiously unloosen details about his life in the ’hood. I learned he never knew his dad. Mom was in and out of jail. He spent many days in the hospital for various ailments, mostly asthma-related.

My wife was the elementary’s latchkey teacher, giving kids with no adults at home a place to go before and after school. Many carried their house key around their necks. My young chessmate attended her class. She said of him, “When that boy comes into a room, he brightens it up. He smiles. He laughs. He brings joy with him.”

But in middle school he had to pick a street gang, Norteño, Sureño or Mara Salvatrucha. If he didn’t, he’d be fair game for all three. He chose one and became a full-fledged active gang member. Soon thereafter one of the other gangs shot at him and missed. He knew who had done it, and he burned their house down in the middle of the night. Nine people were at home asleep. No one was injured, but that’s how he ended up with nine attempted murder charges.

He was only 14 years old and started his incarceration journey at a detention center for juveniles. Then at 16, he was off to hard time in Corcoran State Prison and, finally, to maximum security at Salinas Valley State Prison. For years he did time in “administrative segregation,” which is bureaucratic verbiage for solitary confinement.

In each prison he played chess, and he read. He did a lot of both. “I’m not reading pussy books Mr. Karrer. I’m reading books about revolutions. I want Mao’s Red Book and The Art of War, by Sun Tzu. Oh, sorry for using the word pussy.” Even in prison he remained polite to me.

“Hey,” he wrote, “when I was in Corcoran I played Sirhan Sirhan, and Charlie Manson. We were on the same cell block. But different tiers. Sirhan cheats. Charlie was really good. I beat him once but I don’t think he was really paying attention.”

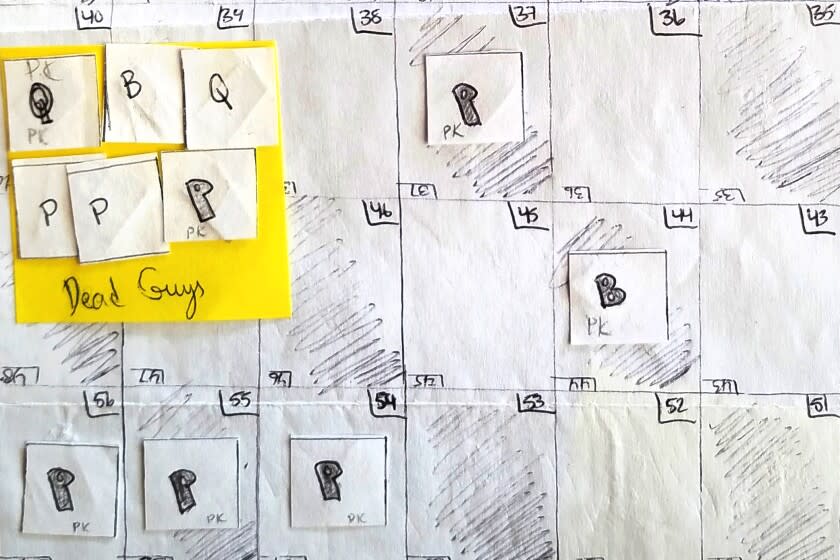

As for my inmates’ chess invitation. We would play on a paper board. In my letter he’d sent a paper chessboard with 64 squares. All done in pencil. He’d also drawn 32 flat paper pieces. My initials on mine. His initials on his. One team white. One team black.

“Teacher-man, we play through the mail. One letter. One move. No CHEATING!”

We played that one game for just short of three years. Every two to three weeks we exchanged letters. We’d made a promise that if he ever got out we’d finish outside in the sun with the wind in his face. On a November day — it was Thanksgiving and his birthday — he was released. He was 26.

The next day we played in a parking lot in Monterey. I’m sorry to say I beat him. But perhaps he was distracted, like Charles Manson was when he played my former student. He kept on getting cellphone calls, and he was wired, super-hyper with freedom.

I took his queen, and it was over.

Since then, he has been in and out of jail. It pains me to say he has not mended his ways. I have not heard from him in some time. I still play chess. I hope he does too.

Sometimes I wish I had let him win.

Paul Karrer is a writer in Monterey. He taught fifth grade for 27 years.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.