Op-Ed: The recent onslaught of book bans is a strategic part of wider attacks on our democracy

In the ever-worsening culture wars, schools have emerged as a battlefront, with fierce arguments raging about the contents of curricula and propriety of particular books. Debating what literature and ideas to teach students is a mark of a healthy democratic society. But coming amid assaults on voting rights, protest rights and respect for dissent, these efforts to repress disfavored ideas and books must be recognized as part of a larger attack on democracy itself.

Since January 2021 more than 150 bills have been introduced in 39 states that would restrict the teaching of certain curricula, mostly on issues of race and gender. Of these bills, more than 103 were introduced since the start of 2022. Twelve have already become law. Roughly two-thirds of the bills target K-12 schools, with the rest focused on higher education, libraries and state agencies. Sixty-two include mandatory punishments for those who violate the bans.

Initially, most of these measures used the misnomer of “critical race theory” in an effort to push back against teachings thought to overemphasize the role of race as the driving force in American history and culture. But more recently introduced restrictions reach beyond any single concept.

South Carolina’s House Bill 4605 seeks to protect students from any material that might cause “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress” on account of their “race, ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, national origin, heritage, culture, religion, or political belief.” Such language, common to many of these bills, is dangerous. It is impossibly broad, opening the door to eliminating an endless range of works and topics. It also undermines one of the very aims of education, which is to help students move beyond their existing assumptions about the world.

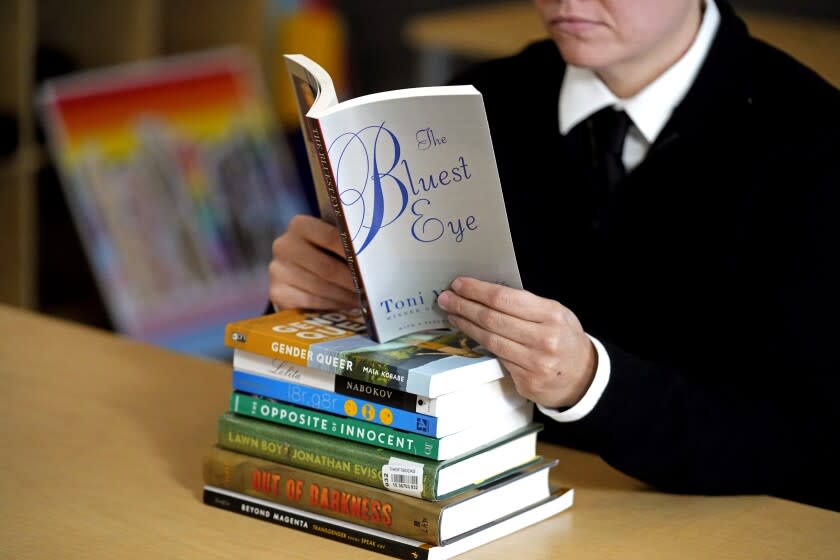

Most book bans target works by and about people of color as well as LGBTQ subjects and storylines. Florida’s Polk County “quarantined” 16 books, including Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” and “The Bluest Eye,” based on complaints from a group called County Citizens Defending Freedom. And as the calls for book banning increase, so does the vitriol that accompanies them: Last fall two Spotsylvania, Va., school board members called for books banned in the county to be burned.

International examples offer an ominous clue as to where this could lead. In the 20th century the South African apartheid state banned 12,000 books, at one point commandeering a steel factory furnace in order to burn reviled texts. And in the 1930s the Nazi Party railed against “un-German books,” staging book burnings of Jewish, Marxist, pacifist and sexually explicit literature.

More recently, in 2018 Iran banned the study of English in primary school to ward off “cultural invasion.” Legislation adopted in Hungary last year banned all curriculum referencing homosexuality from schools in the name of “protection of children.” In 2014 Russia passed a new law adding Nazi propaganda to the subjects it bans and restricts — LGBTQ content, offenses to traditional values and criticisms of the state are among others. Booksellers were so fearful of running afoul of the broad law that they removed Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel “Maus” from stores because of the swastika on the book’s cover, despite its potent anti-fascist message. Last month a Tennessee school board banned “Maus” from its curriculum.

Book bans and curriculum debates in the United States have flared up episodically over time, as rattled communities have sought to pump the brakes on social change in areas including evolutionary science, sexuality and the embrace of ethnic differences. Although some of the arguments being made today — about protecting innocent students from corrupting ideas — echo traditional motives for book banning, the current crusade has a more sinister cast.

The spiking numbers — what the American Library Assn. has called an “unprecedented volume” of book challenges including more than 155 unique “censorship incidents” between June and November, 2021 — indicate that something organized is afoot. In many cases the new bans are not simply spontaneous initiatives by local citizens. Conservative donors, think tanks and organizers have been drafting and shopping model laws, lobbying legislators, recruiting parent and community activists, and providing playbooks on what to get banned and how.

Some of the same institutions and funders fueling book and curriculum bans are mounting parallel, partisan efforts to curb assembly rights, make it more difficult for members of minority groups to vote, commandeer election administration and sow doubts about election integrity. It is all part of the work of a revanchist political movement bent on trampling civil liberties in order to gain and hold power. Organizers have hit upon bans as a potent tool to fire up suburban parents with an issue that affects their own kids’ bookbags.

The techniques being used to enforce these prohibitions feed into an already menacing atmosphere of political schism. School board members in Redding, Conn., and Eureka, Mo., stepped down last year after receiving death threats in the course of curricular battles. In an incident reminiscent of Cold War era purges, a school principal in Colleyville, Texas, was put under investigation for his teachings on issues of race, finally resigning under pressure after being accused of “encouraging the disruption and destruction of our district.” School officials across the country have been similarly targeted.

The blitz on books and curricula is one flank in a wider onslaught on institutions and norms, aligned with part of our country’s resistance to the political and social implications that come with demographic and ideological shifts. Holding fast to democracy means holding fast to books, defending the judgment of teachers and librarians and vigorously upholding the rights to read and learn.

Suzanne Nossel is chief executive of PEN America and author of “Dare to Speak: Defending Free Speech for All.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.