Op-Ed: Russia didn't learn from the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. But Ukraine can

On television and online, commentators reach furiously for comparisons to past conflicts for insights into the Ukrainian-Russian war. How will it ever end?

At the same time, military analysts watch closely to see how lethal new technologies lead to ghastly carnage like in Donbas and Irpin. What can we learn about how to fight future wars?

Surprising answers arise from comparisons to an often-overlooked conflict more than a century ago, between a small nation just elbowing its way onto the world stage and a huge but faltering Western power that just happened to be Russia.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 was a big deal at the time, and it is generally considered the first modern war. The world watched with rapt attention. In the story of this conflict, we can find clues to what is happening, and what may still happen, in Vladimir Putin’s misbegotten and bloody invasion of Ukraine.

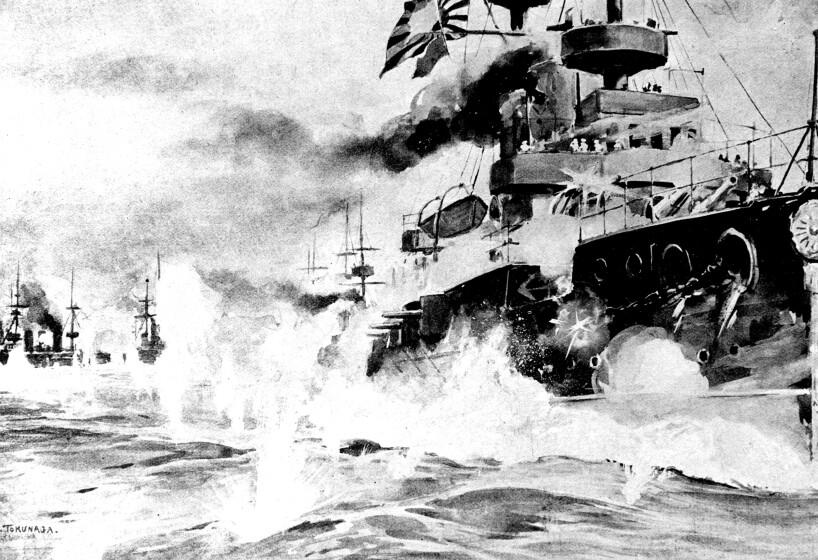

Repeating rifles, machine guns and fast-firing artillery were as new in 1904 as Javelin anti-tank missiles and Turkish drones are today. They all played roles, as did swiftly maneuvering steel warships. The Japanese navy’s destruction of the Russian Baltic Fleet, which had sailed halfway around the planet, shocked the world in 1905 as much as Ukrainian missiles’ sinking of the Russian cruiser Moskva did this month.

But it shouldn’t have. And nor would the struggles of the Russian military today surprise anyone who studied the Russo-Japanese War. Rivers of similarities run through these two conflicts.

Naturally, there were differences, the biggest being that Japan, angered by diplomatic betrayals and Russian expansion in Asia, started the war. It began with a surprise nighttime torpedo boat attack against the Russian fleet in Port Arthur (now the Lüshunkou District of China).

Japan’s navy was modern, its traditions based on Britain's Royal Navy; Japanese sailors even ate curry on Fridays like their English counterparts. (They still do.) Its warships were state-of-the-art and built in England. Thus, a major Western power supplied modern technologies to the smaller of the warring nations, like in the current conflict.

The Japanese soldiers and sailors, swept up in their nation’s extraordinary shift to modernity, were motivated to fight. They were also trained and fed well. And they saw Russia as a greedy, overreaching bully.

Russian soldiers, meanwhile, quickly found themselves under siege in the barren winter hellscape of Port Arthur, thousands of miles from Russia’s major urban centers — and with no real rationale in their heads as to why they were fighting. Supply lines, already extraordinarily long, were easily cut. Russian soldiers’ equipment, training and basic supplies were lacking.

Sound familiar?

The world was sure Russia would win. It had a vaunted military in the grand European tradition. How could little upstart Japan possibly emerge victorious?

Like the conflict in Ukraine that has been livestreamed to and from smartphones, the Russo-Japanese war was witnessed globally almost in real time. Telegraph wires and steam-powered newspaper presses sent new editions onto the streets hourly to feed a hungry public.

The Japanese bottled up the Russian Pacific squadron at Port Arthur, and so Russian Emperor Nicholas II — ever confident of victory, despite setback after setback — shifted tactics and sent his huge Baltic Fleet on an around-the-world voyage to teach the upstart Japanese a lesson.

Around Africa they went, beset by logistical and maintenance problems. The ships were out of date and badly maintained, the crews’ training minimal. So incompetent were the captains that, while off the coast of England, they opened fire on British fishing boats, believing them to be Japanese attackers. Reparations were paid. Reminds one of the seemingly ungoverned Russian forces bumbling around Ukraine.

Finally, after seven months, the Russian fleet arrived in the Far East. Alerted by telegraph from the island of Tsushima, the Japanese admiral, Heihachirō Tōgō, set sail with his fresh, eager fleet to meet the exhausted Russians. In a matter of hours, practically all the Russian battleships were at the bottom of the sea.

Tōgō and his command staff conducted the battle from the open-air bridge atop his flagship, the Mikasa. The Russian admiral, by comparison, remained hunkered within the enclosed steel wheelhouse of his ship. Tōgō thus had a 360-degree view of everything that was happening, and perhaps more importantly, his crews could see him — in the open, watching it all through binoculars as shells whizzed past.

Not unlike Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s stubbornly visible leadership today.

The two countries soon had a negotiated peace. Japan had become a world power.

The legacy of that war was long-lasting, and not necessarily positive. It presaged the horror of World War I battlefields. Anger over the defeat was one reason the Russian people eventually rose up against Nicholas II in revolution. In Japan, overconfidence from this conflict led military leaders to believe that Western powers were hollowed out, with no will to fight, and could be beaten with surprise, brains and guts. This brought us to Pearl Harbor.

The world’s savvy militaries took to heart lessons about trench building, frontal attacks and the power of a well-maintained, well-trained and well-drilled squadron of battleships armed with turreted heavy guns and smokeless powder — just as today’s onlookers are wrestling with the deadly lessons of those Javelins, drones and Neptune anti-ship missiles.

There is still pride in Japan over the victory at Tsushima. The Mikasa is now a museum in Yokosuka near Tokyo. You can visit Tōgō’s cabin and admire his bathtub. Perhaps one day we’ll be able to admire Zelensky’s bathtub in Kyiv.

Wendell Jamieson is a regular contributor to Military History Quarterly.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.