Opinion: The 1619 Project IS patriotic

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I walked onto the stage at Iowa State University’s Stephens Auditorium while seemingly thousands of students and adults were taking their seats. Anxiety pooled in my stomach. My tongue felt stuck in my throat. I was nervous.

Not because I was a keynote speaker at another convocation for college students. Not because I was sharing another Storytellers Project.

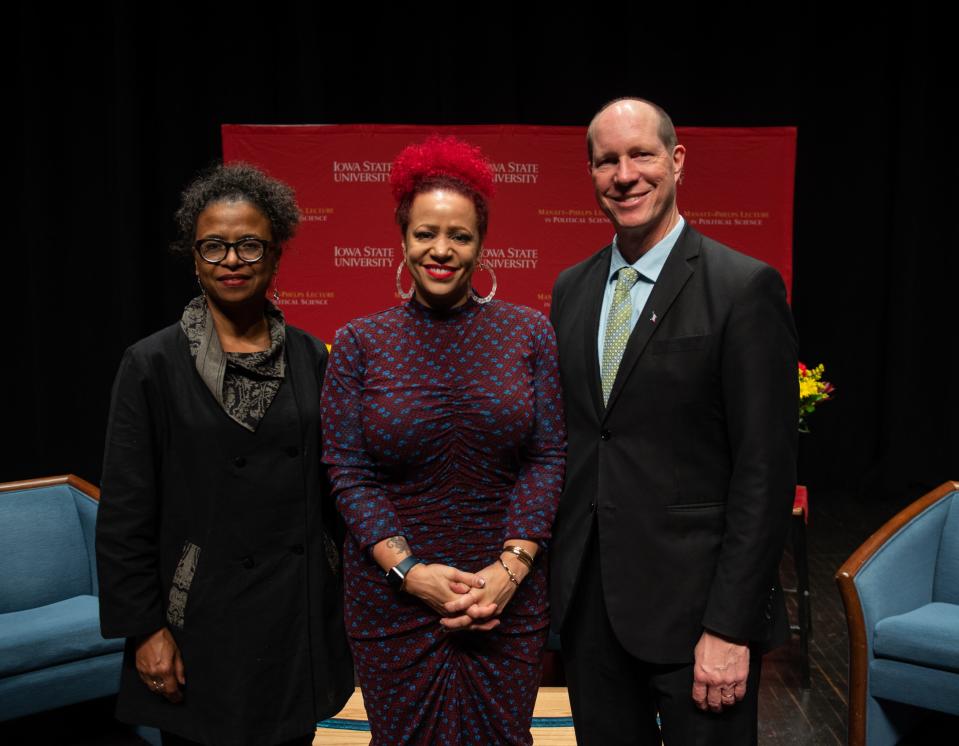

I was simply walking across the stage to meet Nikole Hannah-Jones and ask her to sign my book. In November, the Iowa native was the 2022 Manatt-Phelps Lecture Series speaker at ISU.

More:Iowa native Nikole Hannah-Jones speaks about democracy, the '1619 Project' and what's next

I was nervous because I was finally getting to meet a woman I had long admired. I admire her for the seemingly Herculean task of creating The 1619 Project, which grew from a New York Times Magazine publication to a 590-page book with teacher and curriculum guides to a children’s book, “The 1619 Project: Born on the Water,” to a docu-series that will air on Hulu on Jan. 26. I admire her for propelling the impact of slavery, along with the vital role Black people have played in our democracy, into the spotlight, teaching many a history not taught in schools and keeping it there, despite the efforts of those determined to discredit the work, to tear it and her down. I admire her ability to remain fearless and authentic and unwavering, despite the extreme hatred, criticism, and threats thrown at her.

At the lecture, Hannah-Jones said that many people who are arguing against the project are arguing against it based on something someone has written about it or said about it or posted about it on Facebook but haven’t actually read it. “But I think the most common thing — people think that the book is anti-American,” Hannah-Jones added. “The book has been called unpatriotic, which I don't really take as a valid critique, because it's not my job as a journalist to write something that's patriotic or not.”

Objectively, I think I get why some people consider The 1619 Project unpatriotic.

More:The 1539 Project: Why Black Midwest and Iowa history matters

When you have grown up being taught in every classroom, from math to English to physics to science to history to politics and so on, that every accomplishment or invention that makes this country great is because of someone white, someone who looks like you; when you turn your gaze outward and see all that you have been taught reflected back at you, seeing someone white, someone who looks like you, curing diseases, leading innovative companies, working with and managing you; it reaffirms all that you have learned. So when that Black person has the nerve to kneel during the national anthem, that Black person and his ancestors, who you've learned have never done anything for or contributed to this country’s greatness, you see them as ungrateful and unpatriotic. And when something like The 1619 Project comes along that puts the Black experience at the forefront of history that you have never been taught, it’s unpatriotic and downright blasphemous.

“So my world was really being shaped not just by what we were taught,” Hannah-Jones said, “but by the silences, by the absences. And all of us are shaped by that.”

Like Hannah-Jones and millions of others, I grew up in those same classrooms where I never saw any greatness in math or English or physics or science or history or politics and so on attributed to people like me — or anyone of color; classrooms where, if subjects came up that might put a blemish on all that white excellence, like slavery or the slaughter of indigenous people for their land, the subjects were given mere pages, treated as a side-note and unimportant and rationalized away with teachings like Black people sold their own people so it’s their fault or most slave owners were kind and took care of their slaves or Indians were uncivilized and brutally murdering white settlers. And when I turn my gaze outward today, I have to dig through mainstream media to find someone who looks like me curing diseases or leading innovative companies; sometimes, I may have to go out of my way to find someone at work who looks like me, and I can't remember ever having had a Black manager.

More by Rachelle:Opinion: Nearly 60 Black opera singers performed in 'Porgy and Bess' in Iowa. It was amazing.

But when I read The 1619 Project for the first time, in 2020, I felt a sense of pride. Even though it is not a happy history, even though much of it is a painful way to see myself in history, I can SEE myself in history. Not as a negative afterthought or a brief sidebar, but my race's impact in every area of this country’s foundation and my race’s triumphs and contributions and accomplishments in spite of slavery and inequity, as an integral part of the story. Like white people, I felt a sense of patriotism.

“The only way you could think it is an unpatriotic book is if you don't think Black people can be the vision for patriotism,” Hannah-Jones said. “If you cannot see patriotism through Black eyes and the Black experience and you think patriotism is about waving a flag and being performative and that white people get to say what’s patriotic and what's not, because really, I can't imagine anything more patriotic than being literally enslaved in a country and yet fighting to make your country live up to its ideals for all Americans.”

I joined the audience in a round of hand-stinging applause.

Critics have labeled any real in-depth teaching of slavery and its impact as upsetting and divisive and said that it falsely claims that our country was founded on white supremacy.

The irony is some white people don’t want their kids upset by what they are taught in school, when Black, Indigenous, and other people of color are continually upset by what they are taught in school. The irony is some white people are upset by seeing a history which features Black people at the center and themselves sometimes portrayed negatively, while Black people are upset by predominantly seeing themselves portrayed negatively or not portrayed at all. The irony is that some white people don’t want books like The 1619 Project taught because it's divisive whereas the history that what we have been taught has helped keep us divided.

By denying the reality and effects of slavery and excluding the voices and the stories of the contributions that Black people have made — by force and by choice — to this country, and teaching that only white people are responsible for this country’s greatness, isn’t that in itself the definition of white supremacy?

More by Rachelle:Opinion: A musical about the all-Black female Army unit, the 6888th, is in development. Will Iowa be in it?

“And ultimately,” Hannah-Jones said. “The 1619 Project is about the silences of history and trying to fill in those silences with information.” She also stated that we have been a multiracial country since 1619 so our origin stories have to be inclusive and have to try to help us better understand the society that we have. "The 1619 Project is not doctrine. I don't believe in replacing one doc with another," Hannah-Jones said. "It was always intended to be supplemental, to lead you to be skeptical, to question, not to just accept — again, we're making the argument and either you buy the argument or you don't. But to me, what is valid in any education, is not to simply have your worldview affirmed. But to have your worldview challenged, to have to be forced to see things from someone else's perspective."

When my turn came to have my book signed, I smiled, gave her a heartfelt compliment that I can’t remember, and mumbled my name. I think I mumbled that I worked at the Register, but I can’t remember that, either.

While I remained in my fangirl stupor, others mentioned what I hadn't thought to.

“Dan Manatt is creating a documentary … and he filmed Rachelle talking about Buxton,” said Michele Manatt, the envoy and liaison with Iowa State for the lecture series.

Leo Landis, curator at the State Historical Museum of Iowa, started describing Buxton, before turning to me, “But I should let Rachelle tell you about that.”

Spell broken, I told Hannah-Jones about Manatt’s documentary and the episode he did on Nicodemus, Kansas. I told her about my books on Buxton. After a little back and forth about my book covers, she honed-in on one before saying, “I have that book.”

I felt faint. I wanted to dance. I wanted to squeal. Nikole Hannah-Jones has MY book!

For those who have not read The 1619 Project — including those who deem it unpatriotic without even cracking its spine — I hope you will read it, watch the Hulu docu-series, and join January’s Read Along (where you can download free chapters) between Jan. 23 and Jan. 25 with an open mind before you decide. I also hope you will check out the Manatt-Phelps Lecture Series for future events.

Rachelle Chase is an author and opinion columnist at the Des Moines Register. Follow her at Facebook.com/rachelle.chase.author or on Twitter @Rachelle_Chase.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Opinion: Everyone should read The 1619 Project. Here's why.