Opinion: 46 years after adoption, this Korean adoptee obtained U.S. citizenship. Now she’s advocating to update the law

On July 27, the United States will commemorate the 70th anniversary of the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement, which effectively suspended the Korean War (1950–1953).

Many refer to the Korean War as the “Silent War,” with its long-lasting impacts unknown to the larger population. Among the most prominent impacts, Korean families were displaced and separated in the violence, chaos and poverty of war. Many parents experienced a total lack of economic and social support to keep children with their families.

Seeing the plight of these children, Bertha and Harry Holt from Oregon secured a special act of Congress to create a class of children as “war orphans,” thereby allowing them to bring children to the United States. Even after the cessation of conflict, the U.S. became the primary destination for children whose families were not able or willing to care for their children, resulting in more than 160,000 South Korean children being adopted to the U.S.

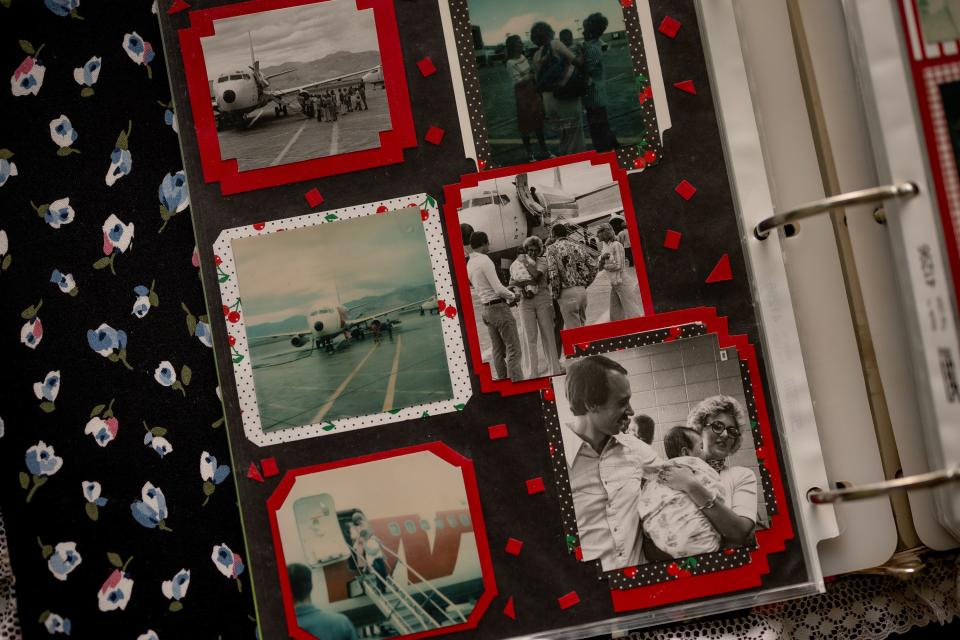

We, the authors of this op-ed, were adopted by Utah families between 1960 and 1980 from South Korea. Our American parents hoped for us to have a better life than they thought we would have in Korea. This implicitly included the promises that U.S. citizenship offers. But those promises required that parents completed extra steps beyond adoption in order for us to obtain U.S. citizenship.

Staci Robison was born in South Korea in 1975, and adopted by a family in Utah six months later. Over the next several years, her parents adopted five more children through international and domestic adoptions. Her parents raised them in a loving home in Utah County. But in her 20s when Robison went to file for a U.S. passport, she and her parents were shocked to find out she was not a U.S. citizen. Her parents had been told by the adoption agency in 1975 that her citizenship requirements were met as part of the adoption process. Her parents were appalled that they had not known about the extra steps required to make their children U.S. citizens.

Robison and her internationally adopted siblings found that lack of citizenship created many limitations, producing uncertainty and fear of being separated from family. Robison could not travel internationally, she had difficulty renewing her driver’s license, applying for certain loans and finding jobs due to limited options.

It took several years and multiple attorneys to obtain the documentation necessary to apply for citizenship. For many years, she had to live on a resident card, which had to be renewed often. Last year, at age 46, she was finally able to obtain her U.S. citizenship. But, she should have never had to go through this ordeal.

Related

Adoption service providers should have ensured that each adoptive family was guided through obtaining their child’s citizenship. Inconsistency in follow-up services meant some international adoptees became citizens while others remained “in limbo” despite being legally adopted by American citizens. This problem creates an unfair disparity between internationally adopted children and biologically born or domestically adopted children.

Adoptees without citizenship are being held responsible and endure the legal, economic, and psychological disadvantages of being marginalized as noncitizens. The responsibility, however, truly lies with the governments, agencies, service providers, legal counsel, guardians and court officers who facilitated intercountry adoption.

Adoptees without citizenship face hardships, including difficulty obtaining jobs, accessing loans for education or housing, or receiving public benefits including social security, medical care and legal justice — despite having contributed to these benefits through their labor and taxes.

Voting and obtaining driver’s licenses are often unavailable. Even worse, more than 50 intercountry adoptees have been separated from their families and communities and forcibly deported to countries where they do not know the language or culture, and lack financial and emotional support systems.

The Child Citizenship Act of 2000 sought to correct this gap by granting citizenship to adopted individuals who were under 18 years of age on its date of enactment — those born on or before Feb. 27, 1983. Unfortunately, due to the arbitrary age cutoff date, an estimated tens of thousands of adult intercountry adoptees born before that date were still left without citizenship, with a significant portion of these being Korean American adoptees.

The Adoptee Citizenship Act, a proposed legislation to close the gap left by the Child Citizenship Act, is a straightforward, commonsense policy solution that changes the effective date of the currently-existing Child Citizenship Act. It ensures that internationally adopted individuals — regardless of age — have the same basic citizenship rights as their parents’ biologically born and domestically adopted children.

In 2022, with wide bipartisan support, the Adoptee Citizenship Act came closer than ever to passing in Congress. On Feb. 4, 2022, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Adoptee Citizenship Act as an amendment to the America COMPETES Act of 2022. In this new legislative session, international adoptees all over the country are encouraging our congressional leaders to finally pass the Adoptee Citizenship Act in the U.S. Senate and the House.

We applaud Utah Congressional Rep. John Curtis for being lead co-sponsor on the Adoptee Citizenship Act last session. Rep. Burgess Owens, R-Utah, was also a co-sponsor of the bill. Our state leaders have also been vocal on this issue. On Feb. 17, 2022, Gov. Spencer Cox signed the Utah Concurrent Resolution to support internationally adopted individuals. This resolution was unanimously passed by the Utah State Senate and the Utah House of Representatives.

We recognize the immense losses caused by the Korean War. Over the decades, we have made Utah our home and cherish Utah’s family values. They are, in fact, why we continue to grow and raise our families here. Our American parents raised us and our siblings as legal, social and familial equals. We call on all of Utah’s congressional leaders, including Sen. Mike Lee and Sen. Mitt Romney, to make this a reality for all international adoptees by becoming a co-sponsor and ensuring the passage of the Adoptee Citizenship Act as soon as possible.

Staci Robison is a paralegal at a Chicago-based tech company. Sara Jones is CEO of InclusionPro. Shelly Johnson is executive vice president of Zions Bank. Jini Roby is a BYU professor emeritus of social work and an international consultant. Kari Holt Larson is vice president of community events for the Utah Jazz. All of the authors are international adoptees from South Korea, raised in Utah, and current Utah residents.