Opinion: American Jewish story shaped by Queen City

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's note: This is one in a series of columns that are appearing monthly during the yearlong Jewish Cincinnati Bicentennial.

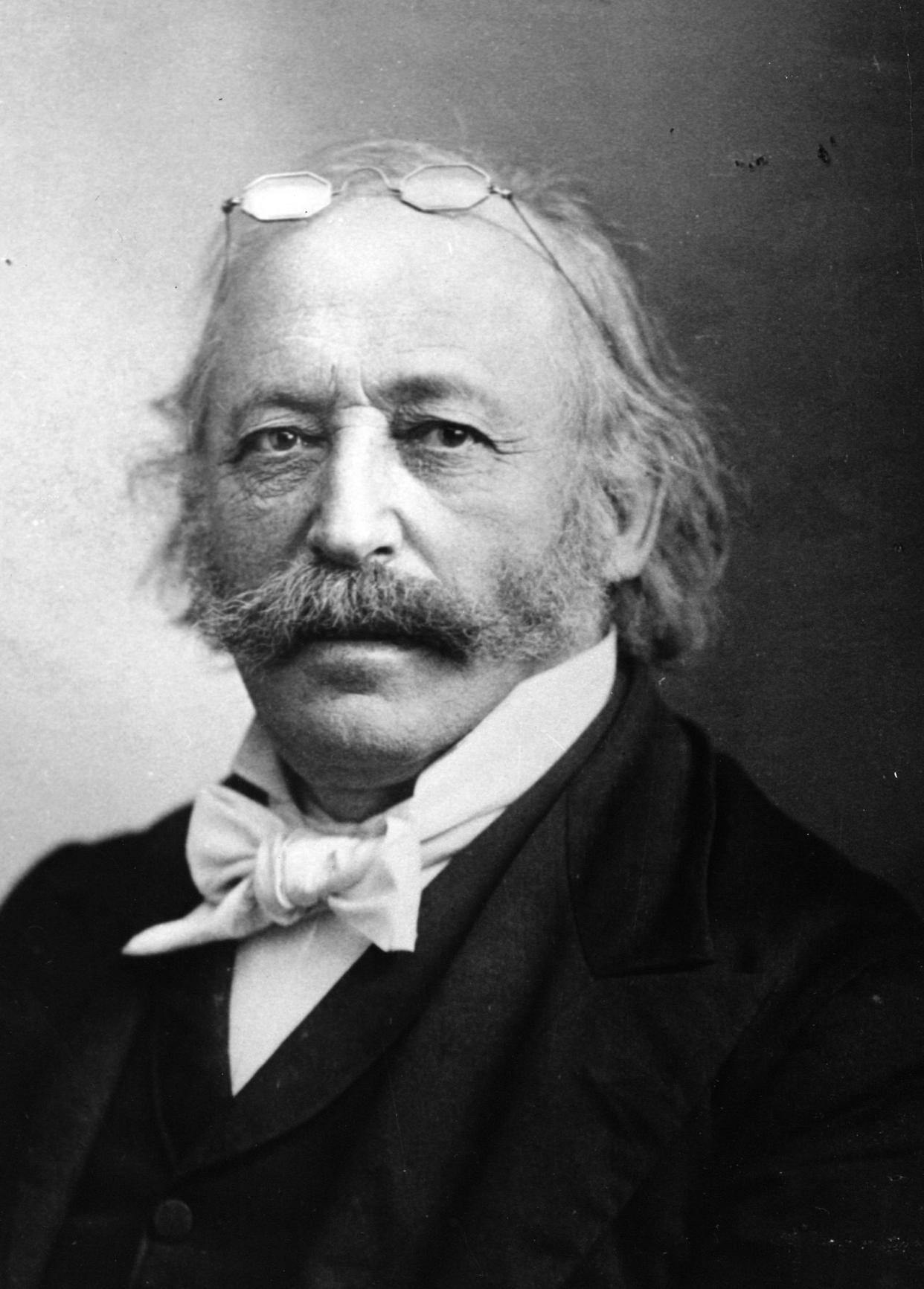

When Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise arrived in Cincinnati in April 1854, he pronounced the city a promising home for "bold plans" and "grand schemes." At the crossroads of the emerging west and the established east, the urbanizing North and the agricultural South, Cincinnati stood out as the largest and most established Jewish community west of the eastern seaboard. It seemed the ideal site for Wise’s intended project of recalibrating an ancient religious tradition to meet the shifting demands of American life.

Within two months of his arrival – and emblematic of his ambitious energy – Wise had founded two nationally distributed newspapers – one in German and one in English. The English one was titled The Israelite – renamed The American Israelite in 1874. Together with Rabbi Wise, Cincinnati Jews would inaugurate a new identity project, unprecedented in recent European or American experience. For them, national identity would not conflict with religious identity. Their Americanness would fit seamlessly with their Jewishness. They would feel, as Wise put it, "perfectly at home in this blessed country."

The success of Wise and his followers in establishing the first long-lasting institutions of national Jewish life secured a central role for the Queen City in the American Jewish story. Likewise, through their leadership in creating the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, a national federation of synagogues, and Hebrew Union College, the nation’s first long-lasting rabbinical school, Cincinnati Jews joined in their city’s self-conscious pursuit of material and moral progress.

Thus, a good number of Cincinnati Jewish men, one-time impoverished peddlers, became not only prosperous merchants, but exemplary citizens of Cincinnati. This sense of belonging was also expressed through extensive involvement in the city’s civic life, exemplified by the Jewishness of both main candidates in the 1900 mayoral election and the 1927 election of Rockdale Temple congregant Murray Seasongood, the reform mayor whose administration transformed national perceptions of Cincinnati from the nation’s "worst-governed" to its "best-governed" city.

The Queen City’s own aspirations faded with the coming of the railroads and its relative lack of appeal as a destination for new immigrants. The city’s Jewish community, however, was able to maintain its leadership in both national Jewish and local political conversations well into the 20th century.

Today, the continuing presence of the majestic Plum Street Temple downtown and of Hebrew Union College in Clifton help Cincinnati Jews maintain an active sense of their community’s historic and national significance. It is, however, somewhat poignant to note that the community now depends upon the legacy of one of its oldest institutions for its current vitality. Absent 21st-century monetary support from the Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati (established in 1995), created from the sale of Cincinnati’s Jewish Hospital (founded in 1850), a number of the city’s key long-standing Jewish communal institutions had seemed destined to fail. The role of the foundation (with assets now pegged at about $500 million) concretizes the reality of today’s communal leaders standing upon the work of predecessors whose commitment and generativity helped to create both a vital city and a pioneering national religious movement.

It can be easy to dismiss the past as old, discredited, news. Indeed, the same city that offered a perhaps unanticipated warm welcome to many Jewish pioneers greeted others, particularly those in its free Black community, with both discrimination and violence. Cincinnati’s past – including its Jewish history, however, presents all of today’s citizens the opportunity to build upon strong foundations. Much of Cincinnati’s strong architectural and civic legacy remains a tangible, if sometimes elusive, presence.

That legacy should not be squandered, taken for granted, or hoarded for the few over the many. Instead, it would be wonderful if lessons from the past could encourage today’s aspiring leaders – those with their own "bold plans," "grand schemes," and the ability to see beyond their own horizons – to build meaningful communities for themselves and for others.

Karla Goldman is Sol Drachler Professor of Social Work, professor of Judaic Studies, and director of the Jewish Communal Leadership Program at the University of Michigan. She is writing a book about the Jewish community of Cincinnati and will be speaking on "American Israelites: Cincinnati Jews and the Shaping of American Jewish Community" at the Mercantile Library on Thursday, Jan. 20 at 6 p.m. and on "Jewish Avondale" at the Avondale Branch Library on Saturday, Jan. 22, at noon.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Opinion: American Jewish story shaped by Queen City