Opinion: Amid bank bailouts, let’s remember the first FDIC recipient

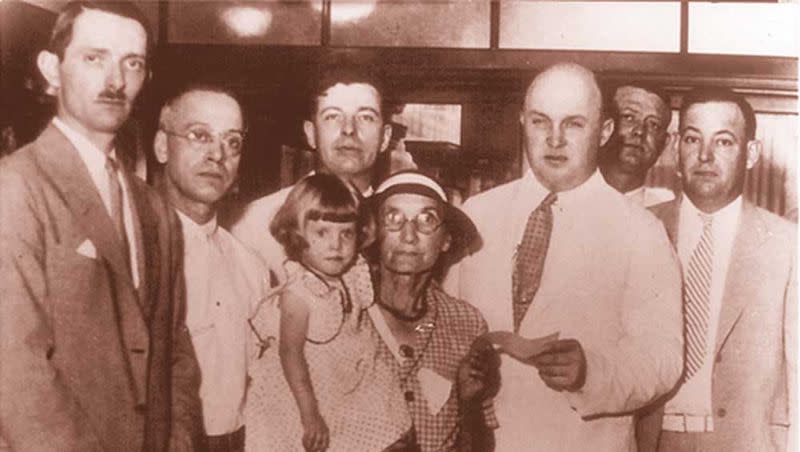

Press accounts described 66-year-old Lydia Lobsiger as wearing a “freshly laundered gingham dress” with a black straw hat on her head on July 5, 1934. What they didn’t describe was the stern matter-of-fact expression on her face as she looked at the camera, her left hand loosely holding one end of a check, with the other end being held by a balding man in a suit, his face expressionless. In her right arm, she carried her 3-year-old granddaughter.

They were surrounded by local and federal officials, all male, all equally grim-faced.

It was what we in the media like to call a “grip and grin” photo, only minus the grins. Few people grinned inside bank buildings in those days. And yet, this photo, and the accompanying story that landed in several newspapers, has a historical significance that seems heightened today.

Lydia Lobsiger of East Peoria, Illinois, was receiving a check for $1,264. That represented all the money she had in the Fond Du Lac State bank before it suddenly failed, plus the $14 she had deposited for a different, 12-year-old granddaughter. It had been all the money she had in the world — a sum carefully collected through the years she raised two children.

But this wasn’t just any check. On this day, she was the first official beneficiary of the new Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which Congress had established in an effort to put an end to the “runs” on banks that had forced so many of them to close during the Great Depression.

Sixty-one banks would fail that year, but by some estimates more than 9,000 had gone under between 1930 and 1933.

Over its roughly 90 years, the FDIC seems to have tried to stay well behind the line that might tempt banks to throw caution to the wind. In 1934, it insured deposits up to $2,500, or about $56,000 in today’s dollars, using a simple inflation calculator. Today, the limit is $250,000.

Or, I should say, it was last week. After the Silicon Valley and Signature Bank failures, limits seem to be gone. The Biden administration has announced that the federal government will make good on the deposits of all the banks’ customers, regardless of the size of their accounts.

Related

Governments, of course, can’t do anything to the economy without unintended consequences. Every time they squeeze the economic balloon on one end, something bulges somewhere else. Critics have been quick to seize on this decision, and for good reason.

Writing for the libertarian-leaning Reason magazine, Elizabeth Nolan Brown debunked the president’s assurances that taxpayers won’t be on the hook for these bailouts. Banks are taxpayers, too, she said, and the ones who were responsible with their investments will now have to pay higher fees to cover those who weren’t. They will do this by passing the cost onto their customers, also taxpayers.

The New York Post quoted people upset that “top tier venture capital firms” were among the wealthy depositors being bailed out, while investors, such as large mutual funds that hold the retirement accounts of everyday workers, people who might be described as modern-day Lydia Lobsigers, were not.

Others, such as Charles W. Calomiris, the former chief economist of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, argue that deposit insurance of any amount is harmful to the banking system. Its popularity, he wrote in the Wall Street Journal, “reflects public ignorance about its costs and about how a disciplined, uninsured banking system could operate as an alternative.”

And yet, just as when banks faced pressures nearly 15 years ago, it’s hard for politicians to let go of the reins and let the economy regenerate itself through a forest fire of destruction. The failure of two or more banks might not have reverberated too far, but a panic-stricken, social media-immersed nation could generate runs on other banks, large and small, without much encouragement. And economic chaos tends to breed political extremism and societal volatility.

Related

Who wants that?

Even if the federal government hadn’t acted, local leaders, including Gov. Spencer Cox, have said they were devising a plan to help Utah businesses and venture capital firms affected by Silicon Valley’s collapse.

Ultimately, it’s hard to look into the face of someone like Lydia Lobsiger and tell her she is out of luck because her bank let her down. That’s especially true when you read the accounts of how she believed that “work and economy were the way to security and happiness. She had acted upon that theory through 40 self-reliant years as a housemaid and laundress,” as a United Press story at the time said.

The complicated truth is that wealthy depositors, startups, venture capitalists, investors and regular folks are interconnected in a web of jobs, innovation, opportunities and retirement funds.

It’s also true that today’s bank failures are connected to the generous pandemic stimulus checks from the Trump and Biden administrations, which helped feed the inflation that led the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates and put the long-term assets of certain banks at risk.

And, yes, it’s also true that blowing the lid off FDIC limits will have consequences of its own.

No wonder the folks in that photo from 1934 weren’t smiling.