Opinion: Exchange with Benny Napoleon has stuck with me for 10 years

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

To mark the 10-year anniversary of Detroit's historic July 18, 2013 municipal bankruptcy filing, the Free Press is examining what has changed, what hasn't, and why. Find more coverage at freep.com.

The 2013 mayoral primary was shaping up to be a horse race: Mike Duggan's move to Detroit hadn't satisfied the statutory timeline; he had failed to qualify for the ballot, and was mounting a longshot write-in primary campaign. Duggan and Wayne County Sheriff Benny Napoleon, a former chief of the Detroit Police Department and a widely respected native Detroiter had traded the front-runner spot throughout the spring and summer.

The mayoral race was complicated, largely defined by what was happening in Lansing. Gov. Rick Snyder had appointed an emergency manager for the financially struggling city on March 14, and Detroit had filed for bankruptcy on July 18, the shoe that had been dangling overhead for almost a decade finally dropping. Emergency manager Kevyn Orr would hold the reins of city government until late the following year.

That summer, the Detroit Free Press editorial board was interviewing candidates in advance of our primary endorsements. When it came to Orr's appointment, Duggan's posture was pragmatic; rejecting the need for an emergency manager, he wasn't mounting strident public opposition.

Not so Napoleon. The sheriff, who died of COVID-19 in 2020 and whose loss is still deeply felt, rejected the state's rationale for appointing an emergency manager, whom he believed had been installed only to lead the city into bankruptcy.

Maybe local elected leadership had failed, Napoleon reasoned, but that was an argument for new leaders, not — as many Detroiters viewed Orr's appointment — a state takeover.

The conversation grew heated, as endorsement interviews sometimes do. Napoleon had been defensive, at times outright angry, about what he saw happening to his beloved city.

"I don't believe that as the leader of this city, I should roll over and let them treat us any kind of way they want to," he said, of a Detroit mayor's relationship to state government. "I think there's a respect level here that has to go up with the City of Detroit."

What about police protection, we asked, or functioning ambulances? What about the city's promises to retirees or its obligations to current residents, none of which it could afford?

Napoleon had spent his entire career in law enforcement, he told us. He'd worked his way up the ranks of the Detroit Police Department. He'd cut the grass of abandoned homes in his neighborhood. His grandfather had been a sharecropper in Tennessee. The state takeover was intolerable.

"It's wrong," Napoleon told us, finding the words that would convey the intensity of his feeling. "It's un-American. And the only reason someone would approve of it is because it hasn't happened to them."

That exchange has stuck with me for a decade for two reasons. In that moment, I saw the depth of his feeling, the anger and shame and frustration that this had happened to Detroit. Power had once again been taken from those who had fought so hard to obtain it.

I understood what Napoleon meant to tell us. But I also understood what he didn't say.

2 Michigans

I'd lived in Detroit's suburbs, Hamtramck and Dearborn and Royal Oak and Clawson, since I'd moved to Michigan in 2000. In July of 2013, I owned a home in Ferndale. (I moved to Detroit later that year, and I'm never leaving.)

If the cities of Birmingham or Grosse Pointe or Ferndale, were unable to provide essential services like streetlights or police and fire protection or timely EMS service, the state wouldn't have to force a takeover, because residents of those communities would march on Lansing, demanding state government fix it and fix it now.

I'm a voter and a taxpayer, and Lansing, the way I view it, has an obligation to care for my health and welfare. I am entitled to such services, and I expect them to be provided — that's the whole point of government — thanks, in part, to a lifetime of institutions nearly always working to my advantage.

I felt no affinity for the GOP-controlled Legislature of 2013, or Snyder, a Republican. But I can't imagine feeling disenfranchised if the elected officials in Ferndale had been temporarily supplanted by those Lansing Republicans, if the stakes had been as high as they were in Detroit.

What Napoleon had deftly articulated was the vast divide between Black Detroiters and white suburbanites.

Women had to fight for the right to vote. But that battle, at least for white women, was won in 1919, and for more than a century, we've largely enjoyed access to the ballot box. My grandmother, who was born in 1900 and died in 1997, was one of the few Americans I knew who'd lived through that time.

Benny Napoleon was 10 in 1965 when the Voting Rights Act passed, finally abolishing discriminatory practices intended to bar Black votes that endured for nearly a century after the Fifteenth Amendment passed. My Black peers can speak of great-grandparents who were enslaved, or tell vivid family stories just a generation back of blatant bigotry and racial animus from institutions and from their fellow Americans. Too often, I've heard stories from Black friends of their own toxic experiences with implicit or explicit bias, of their fears that their children will be hurt or killed by police for whom "Black" and "criminal" can run together, who share with me that they've experienced interactions with white people who reacted as though these accomplished Black professionals must be minimum wage workers at the businesses they were patronizing. And the Black vote is still under attack.

The victories are more recent. More tenuous. So the loss, here, of hard-won Black political power and authority, at the hands of outsiders — Napoleon felt it, in a way it is difficult for white Americans to imagine.

The point of it all

When I started covering Detroit in 2005, bankruptcy was already being whispered in city hall.

Detroit's population decline, coupled with state cuts to taxes distributed through statutory revenue sharing, put the city on impossible financial footing. Detroit had stopped filing the standard year-end audits required by the State of Michigan, the ones that reconcile the projected budget with its actual revenues and expenses, on time. The city had logged years of deficits, engaging in a variety of risky financial maneuvers to restructure its impossible debt burden. It wasn't clear how long Detroit would be able to pay its bills.

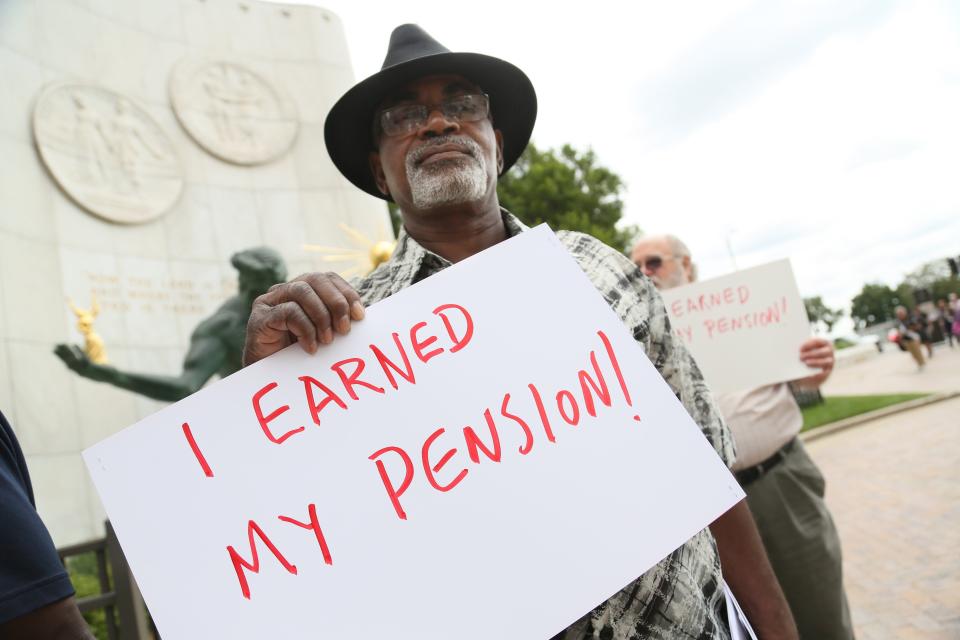

But the city's most significant costs were its obligations to pensioners, and those couldn't be solved by re-financing, even the notorious credit swaps that brought the city a few years of breathing room, and became disastrous later. It had repeatedly short-changed the pension system, rolling missed payments into its future obligations, doing the same thing the next year and the next. Cuts to retiree pensions and health care were the most unconscionable part of Detroit's bankruptcy, but an even worse fate loomed: Deficits in the city's retirement funds could have caused Detroit to default on its pension payouts, leaving the retirees it had promised to support with nothing.

The conditions for a state takeover, and likely for bankruptcy, had existed since at least 2005. But sending an emergency manager — a necessary precursor to bankruptcy — to Michigan's most staunchly Democratic city was a decision a Democratic governor simply could not make. Enter accountant Snyder, who saw Detroit's fiscal crisis as a balance sheet problem to be solved, not a political minefield to navigate.

The promise of the bankruptcy was that things would get better. The extreme step of emergency management is only justifiable if it results in an improved city. And in a lot of ways, Detroit is better. City government has a surplus, not a deficit, forward-looking budgets and sound financial projections. The retirement funds, supported by the bankruptcy's grand bargain, are on solid footing. But it seems to me that in the last decade, Detroit and Lansing have come no closer.

What happens next?

There's a Democratic majority in Lansing, now, for the first time in 40 years, and a Democratic governor. But a quirk of the state's bipartisan redistricting process has left Detroiters with less direct representation in the Legislature than under the old gerrymandered maps that reliably delivered a Republican majority in a state split just about evenly between blue and red. No Black Detroiter serves in the U.S. Congress.

I do not believe that any of this has caused Detroiters to feel more kinship with our government institutions.

About 34% of the Detroit's registered voters cast ballots in the 2022 gubernatorial and legislative elections; in 2021, just 18% of the city's voters turned out for that year's mayoral contest. There's not just one reason why folks don't vote; the continued drain of middle-class, better educated residents from the city — those most likely to vote — certainly plays a role, along with infrastructural hurdles. But it's hard to argue that disconnection from political institutions doesn't have something to do with that.

Over the summer of 2013, emails had emerged showing Duggan had communicated with state officials before Orr's appointment. (Duggan maintains that his intent had only been to deny the need for an emergency manager.)

In the endorsement interview, Napoleon spoke plainly, "I don't have a relationship with Lansing."

Detroiters are Michiganders, entitled to the same support and deference from Lansing as any resident of this state. What is Lansing going to do to ensure that residents of Michigan's largest city believe their state government views them as constituents?

Nancy Kaffer is the editorial page editor of the Detroit Free Press. Contact: nkaffer@freepress.com. Submit a letter to the editor at freep.com/letters. Become a subscriber at Freep.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Opinion: What Benny Napoleon taught me about Detroit's bankruptcy