Opinion: Barbie doesn’t belong in a box

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s Note: Sara Stewart is a film and culture writer who lives in western Pennsylvania. The views expressed here are solely the author’s own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

The release of the hotly-anticipated “Barbie” movie is almost upon us, and the cultural buzz has never been louder. The film, starring Margot Robbie in the lead role and directed by Greta Gerwig, debuts on July 21 (its distributor and CNN share a parent company, Warner Brothers Discovery). I haven’t seen Gerwig’s movie yet, but I do know that, along with almost every woman I know, I have had a lot of feelings about the resurgence of Barbie in public consciousness over the past six months.

And all those feelings are … complicated. In the pantheon of iconic children’s toys, this buxom doll looms especially large as a Rorschach test of gendered playtime. Is Barbie a trailblazing feminist? A representative of the worst sort of body-image policing? Is she a liberator of girlhood dreams, or an outdated tool of the patriarchy? The answer seems to be: All of the above.

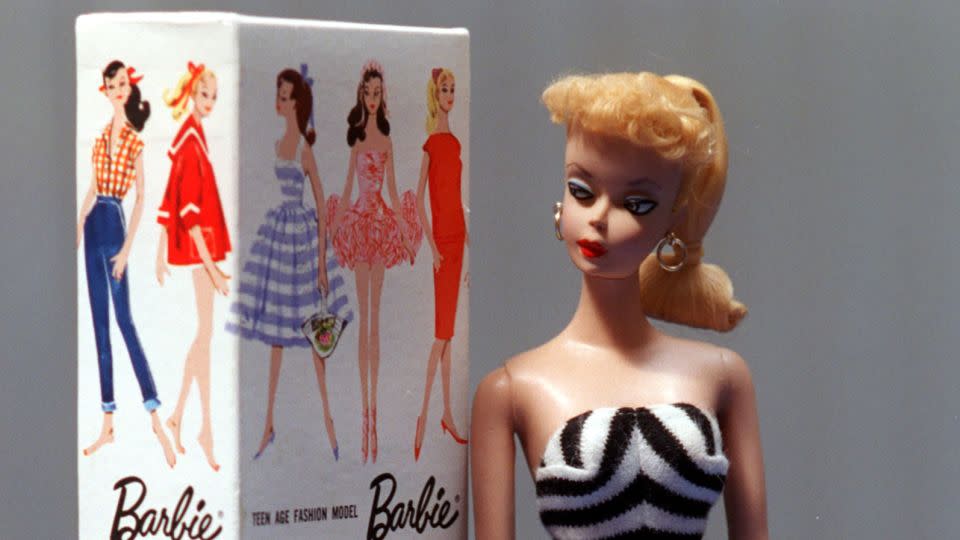

Born into a girls’-toys landscape that was populated almost exclusively with baby dolls, Barbie was inspired by a raunchy German gag gift spotted in a shop window by the co-founder of Mattel, Ruth Handler, and her teenage daughter in 1956. Handler was captivated by the small doll’s blond ponytail, lined eyes and pouty lips. A few years later, Barbie was born.

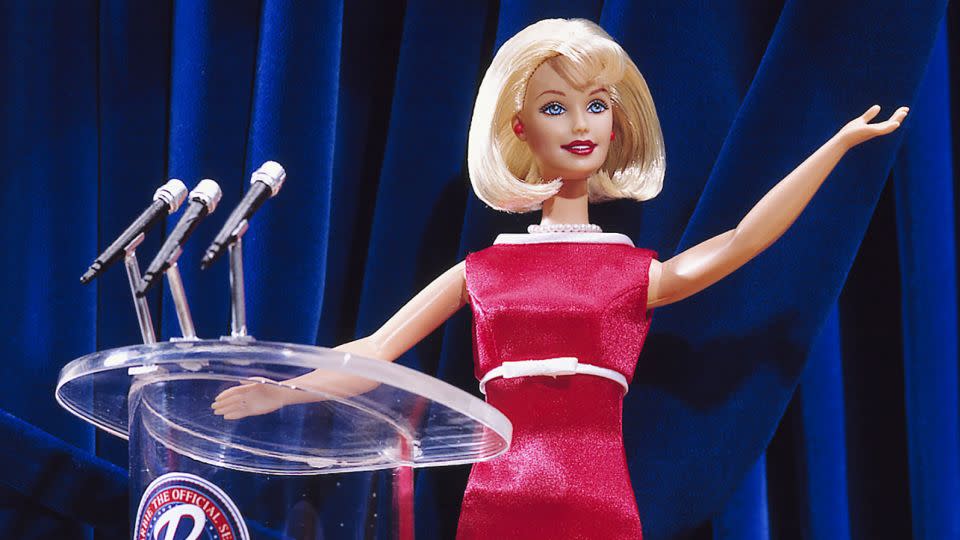

Barbie quickly became a unique icon of womanhood — so it’s hardly surprising that she means so many different things to different people. She was a bold new innovation in American toys, an avatar of adulthood who would expand into over 250 professions and, more recently, a wide range of ethnicities and body types. Today, there’s even an “Inspiring Women” line of Barbies based on real people, including Rosa Parks and Jane Goodall.

But it hasn’t all been empowering. Gloria Steinem has said that Barbie “was pretty much everything the feminist movement was trying to escape from.” A 2016 study found that ultra-thin Barbie dolls have had negative effects on very young girls’ body image, and a Huffington Post story from 2011 explored the horrifying reality of building a life-size Barbie: “At 5’9” tall and weighing 110 lbs, the traditional Barbie would have a BMI of 16.24 and fit the weight criteria for anorexia. She likely would not menstruate,” the article said, adding that “If Barbie was a real woman, she’d have to walk on all fours due to her proportions.” (She does now come in various body types.)

Plus, there’s another aspect to Barbie that gets overlooked in the feminist-versus-oppressor debate about her impact on the little kids (and not-so-little kids) who play with her. For some of us, Barbie was our first glorious introduction to camp. As Susan Sontag wrote, “Camp is a vision of the world in terms of style — but a particular kind of style. It is the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not.” In a world of dolls designed to look like realistic babies, Barbie is nothing if not exaggerated. With her big hair, big boobs and molded-high-heel feet, she’s essentially doing female drag: an over-the-top riff on the notion of womanhood. And despite the shameful slurs coming from the right, kids love a drag queen, as shown in the quotes from one story-hour anecdote: “I love your dress!” “It’s so big and fluffy!” “I love glitter!”

Importantly, despite being a representation of hyperfeminized adulthood, Barbie has, throughout her endless reinventions, never had kids — a remarkable achievement for a 64-year-old toy for girls. If you were a kid who, like me, was deeply bored by the idea of playing mommy, Barbie represented liberation from that game. It’s a feeling Gerwig channeled masterfully in the first teaser for the film, which riffed on Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968).

Was the childfree Barbie still a wildly gendered toy? Obviously — but she was also the star of the most grandiose and glamorous stories you could make up for a single, impossibly proportioned gal on the go. For many kids, the appeal didn’t lie in how much you wanted to literally look like her — it was in the freewheeling lifestyle she represented. Imagine how meaningful this would have been in Barbie’s early years especially — an era in which little girls were being actively groomed for motherhood as life’s most important calling. (That’s not to say it’s not still happening, either. As one expert suggests, “consider doing something gender-nonconforming with your children’s existing dolls, such as having Barbie win a wrestling championship or giving Ken a tutu. And encourage the boys in your life to play with them too.”)

With her cartoonish proportions, Barbie has always invited cheeky takes. She’s been co-opted for satirical purposes countless times over the years. She starred in Todd Haynes’ “Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story,” the “Carol” director’s 1987 dark stop-motion short film about the life of anorexic singer Karen Carpenter. She was painted by Andy Warhol in in 1986. And in 1993, a performance artist group calling themselves the Barbie Liberation Organization swapped the voice boxes of Teen Talk Barbies and G.I. Joes, resulting in a macho soldier who said “Math class is tough!” and “Wanna go shopping?”, and a Barbie who said things like “Vengeance is mine!”

The fairly eye-roll-worthy Teen Talk Barbie, incidentally, also inspired the Malibu Stacy dolls of “The Simpsons,” Lisa’s willowy doll who said “Don’t ask me, I’m just a girl!” But even the face-palm missteps along the path of Barbie’s development are pretty funny; the 1965 Slumber Party Barbie who came with a diet book whose one instruction reads “DON’T EAT!” could be interpreted as a wink at the ham-handedness of diet culture.

Among former Barbie owners, a classic rite of passage is swapping stories of all the irreverent stuff you did with, or to, your dolls. Gerwig shared her own tale of misdeeds on the pink carpet at the film’s premiere: “First, you start by taking the braid out, then you brush it out, then you see if you can curl it with a curling iron − you can’t, it melts − and then you cut it all off,” she said.

From the looks of it, Kate McKinnon will be playing this version — “Weird Barbie” — in the movie. Impeccable casting, as usual, for Gerwig’s movies.

The existence of so many opposing interpretations of her meaning is kind of the point: The beauty of Barbie is that she can be anything. (Or, as the tagline for the film puts it, she’s everything.) Which is exactly why she still resonates with kids and why generations of adults are watching trailers for Gerwig’s movie with unadulterated delight. So let’s not put Barbie, or the generations who’ve loved her, in a box.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com