Opinion: On behalf of sanctimony, Texas strikes a blow on books

The Victorian era ended in 1901 with the death of Queen Victoria. But Victorianism, the priggishness that led galleries to apply fig leaves to cover the private parts of classical sculpture, lingered. Puritanism, which the pugnacious journalist H.L. Mencken called “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy,” is now resurgent.

Last March, Hope Carrasquilla, the principal at a school in Tallahassee, was forced to resign over parental complaints: Sixth-grade students were being exposed to images of David, Michelangelo’s celebrated statue that is both majestic and nude. In Arkansas, librarians face criminal charges for making “obscene” books available to minors.

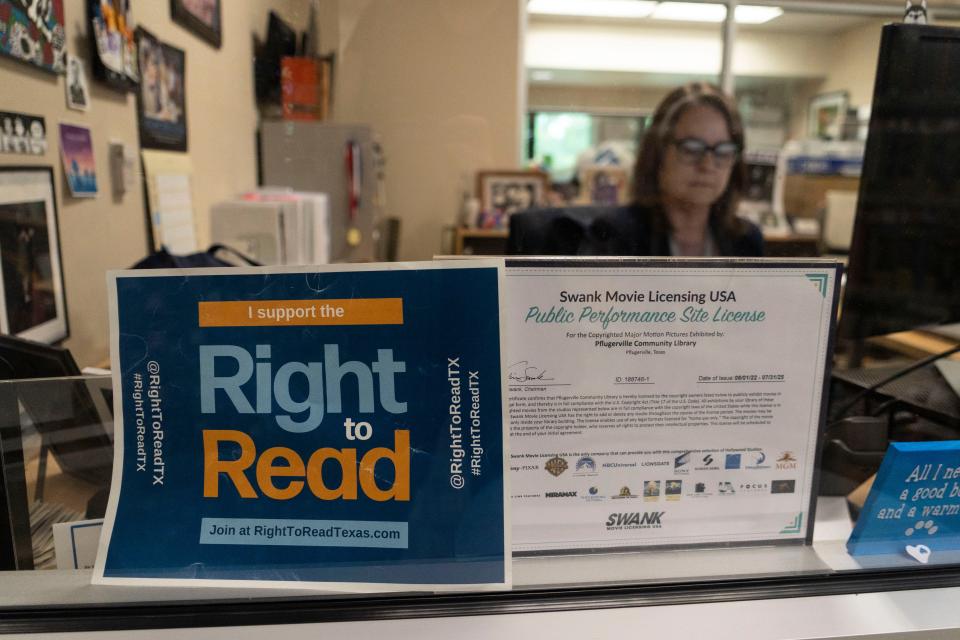

Texas now strikes its own blow on behalf of sanctimony. House Bill 900 will ban all “sexually explicit books” from the state’s school libraries. After passage by both houses of the Texas Legislature, it awaited the likely signature of Governor Greg Abbott. The bill’s author, Rep. Jared Patterson (R-Frisco), declared: “After more than 18 months of fighting alongside concerned moms and dads throughout Texas, I am proud to say we have passed legislation to halt the sexualization of Texas children through library materials.”

Texas children are sexualized through biological development. They are going to be curious about sexuality despite the wishes of their elders. The greatest literature often deals openly about the human body, and it would handicap Texas students to deny them access to it. The revolution of modern art was fought in favor of candor, and it took a series of monumental court decisions to overcome bans against books by Theodore Dreiser, James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, Vladimir Nabokov, and others. No student of literature can now afford to be ignorant of those works.

Not every sexually explicit book possesses literary merit. And not every book merits placement in a library. However, some of the greatest works of the past century, including “Ulysses,” “Sister Carrie,” “Women in Love,” and “Lolita” have run afoul of censors, who have judged them “obscene.” The same vague complaint has been used to expurgate, if not ban, earlier works, including Song of Songs, “Tale of Genji,” and “Gargantua and Pantagruel.” The criterion for censoring books has been nebulous and dependent on the shifting whims of the censors.

Current censors appear most outraged by texts about the sexuality of LGBTQ, African American, and Latino characters. The philosopher Bertrand Russell noted that: “Obscenity is whatever happens to shock some elderly and ignorant magistrate.” Much censorship is driven by a desire to make the censor seem righteous rather than a genuine concern for the effect on a reader.

Instead of an indecent rush to exclude merely because bodies are depicted in contact, it would be more reasonable to examine the total context of a passage and the artistic quality of the work. Why not err on the side of inclusion, especially since children are always going to find ways to find material deemed taboo? In fact, forbidden fruit always seems sweeter. Faced with the full smorgasbord of available writing, let readers develop their own diets. “Let children read whatever they want and then talk about it with them,” suggested bestselling children’s author Judy Blume. “If parents and kids can talk together, we won't have as much censorship because we won't have as much fear.”

Fear is driving too much contemporary politics. Education is the antidote to fear. And the foundation of education is the ability to read widely and wisely.

Kellman is a professor of comparative literature at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Opinion: Texas strikes a sanctimonious blow on books