Opinion/Brown: Artificial intelligence and your child’s education

Back in the 1980s, I was teaching English at a private school in Vermont when one of my seniors lost his temper.

“You’re saying we need to know all this stuff,” he said, “but we don’t. Look, my father’s secretary is already fixing my papers for me. I already have a private secretary. Why should I assume, if I already have one now, that I won’t have one later? I don’t need this!”

And there, dear reader is the question. Forty years of technology have put a service once available to a rich man’s son into the hands of us all. Your children’s teachers want your kids to be able to think, find reliable information and write intelligently about it on their own. But they’ve always found shortcuts.

Back in the day, they could copy verbatim from books and offer bogus footnotes that looked scholarly but referred to nothing. The chances of an over-burdened teacher actually checking were close to nil. Kids at that same school threw their library books in the dumpster in June — or razored the incriminating pages out … affluent teenagers honing their skills at white-collar crime.

The internet made it far easier, but soon, academics purchased software that could scan the web too — and flag plagiarized content. What our schools have always wanted is to train our children how to research new information, how to use it honestly and how to cite the sources so readers could be reassured the papers were factual — and were being directed to the reliable source material if they wanted to learn more. That’s the whole idea.

Joy ride:Brewster couple retools 70-year-old bus into an RV

Meanwhile, computer technology pushes for machines that can solve problems for us faster and more reliably than humans can. For the layperson, this has seemed like trying to create a brain in a box … like a super-bright Hollywood robot. But artificial intelligence (AI) isn’t like that. It’s an attempt to scan all writings on all subjects, everything we can find today when we search for it specifically and teach computers how to synthesize all of this on demand.

While I’m writing, Microsoft Word is constantly offering me suggestions for my next word or phrase. When I get emails, Google offers me a short menu of appropriate replies. In short, my computer is pre-reading my mail and trying to read my mind — and getting better at both all the time.

OK, back to school. Teachers and professors give their students assignments to research something, or analyze it or just think about it. Not that long ago, the lazy ones could scan for papers written by others and purchase them online for their own use. And often, academic software could catch them at it. Now, we’re entering an age when AI can, at the speed of light, research their topics and write a paper for them. And the result will be unique — and thus untraceable. What are we to do?

Curious Cape:Worker entombed in the Sagamore Bridge? We unravel a Cape Cod urban legend

God forbid we raise a generation of children who’d become helpless if the power went off. So let’s imagine a research paper with an interesting topic a kid could work on. The first task is to assemble a “fact-pile” of useful facts, statistics and quotes. The site is listed and under it, the facts and quotes are listed. Not a reprint, just the useful tidbits … quotes in blue ink and facts in red. That will be track #1, the data track.

That completed, the kids spend a class period writing longhand what they think the problem is they’re looking at, and what solutions to it might look like. It’s what they’d say out loud if you had a conversation about it. This will become the narrative track. Teachers read the handwritten draft, make a few written suggestions, then the kids type it up and the teacher keeps these, the handwritten and typed drafts.

Cape business:Whiskey, literature and Alcoholics Anonymous: Life of a 90-year-old Cape Cod restaurateur

Only then will the students merge their supporting data into their narrative tracks, quotes in blue, data in red and their narrative track in black. The result is an anatomy chart of how the original thinking is supported by research — and it all belongs to the student. It’s plagiarism- and AI-proof. All the teacher needs to do is compare the finished products to the handwritten drafts. This works. My Cape seventh-grade students did this for years.

In 1968, Robert Kennedy was about to deliver a campaign speech when someone told him Dr. King had been murdered. You can Google his resulting speech. What Kennedy did was what you want a good education to do. He told stories; he quoted ancient Greek playwrights; he touched the heart; he made sense. It’s what we want our kids to do: synthesize reality all by themselves.

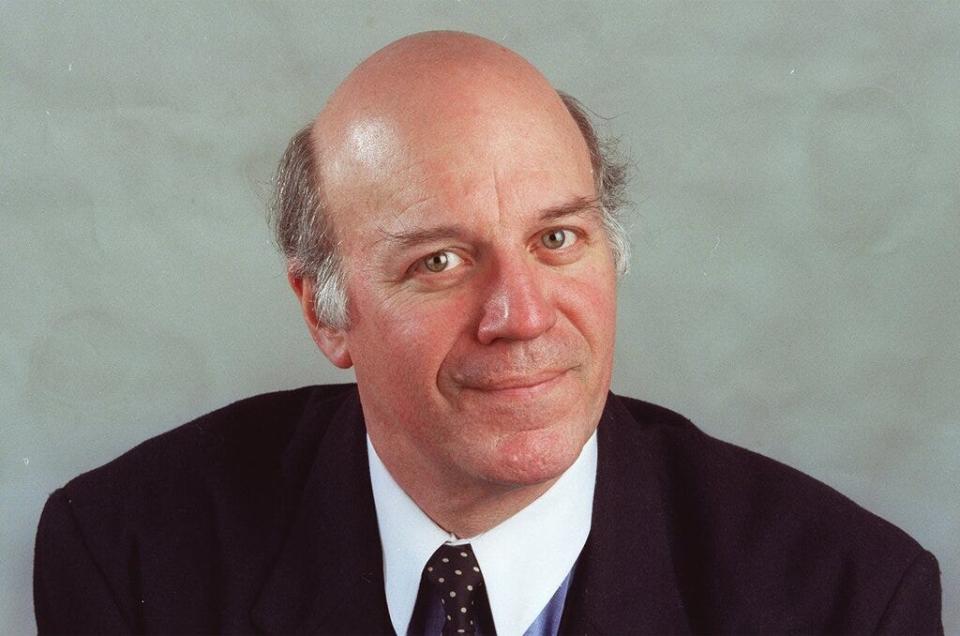

Lawrence Brown is a columnist for the Cape Cod Times. Email him at columnresponse@gmail.com.

Stay connected with Cape Cod news, sports, restaurants and breaking news. Download our free app.

This article originally appeared on Cape Cod Times: Opinion: Artificial intelligence a threat to critical thinking skills