Opinion: The end of AIDS

Carol Zulu died of HIV/AIDS in 2009. She was 15.

Carol had been ill for some time before she went to live at the Children’s Resource Center outside of Lusaka, Zambia, but once she had regular meals and a stable environment, she began to thrive, at least in some ways. Internally, AIDS continued the destructive march that would take her life.

When I first met her in 2006, she was 12 years old, but looked like she might have been 7. Her rich brown skin, bright eyes and carefully braided hair were beautiful, but it was her charming personality that really drew people to her. She was cheerful, kind and worried about the well-being of others. She sang, wrote poems and made sure the people around her were taken care of. The founder of Mothers Without Borders, Kathy Headlee, called her “love on legs” and said she represented the best in all of us.

The year she died, Carol was one of some 1.8 million people worldwide who died of HIV/AIDS in those 12 months, with the vast majority of the dread disease’s victims in sub-Saharan Africa like Carol. Over 40 million people have died since the disease was first identified in 1981, and approximately the same number are currently living with HIV. It was therefore stunning to read in this year’s UNAID’s report that there is a path to ending AIDS deaths by 2030, less than seven years away.

Meeting Carol was not the first time I had been personally touched by a person who ultimately died from AIDS. My uncle, Nathan Smith, contracted HIV from contaminated blood he received as part of his ongoing treatment for hemophilia. He died in 1986, during a fear-filled time when people with AIDS were shunned and ostracized.

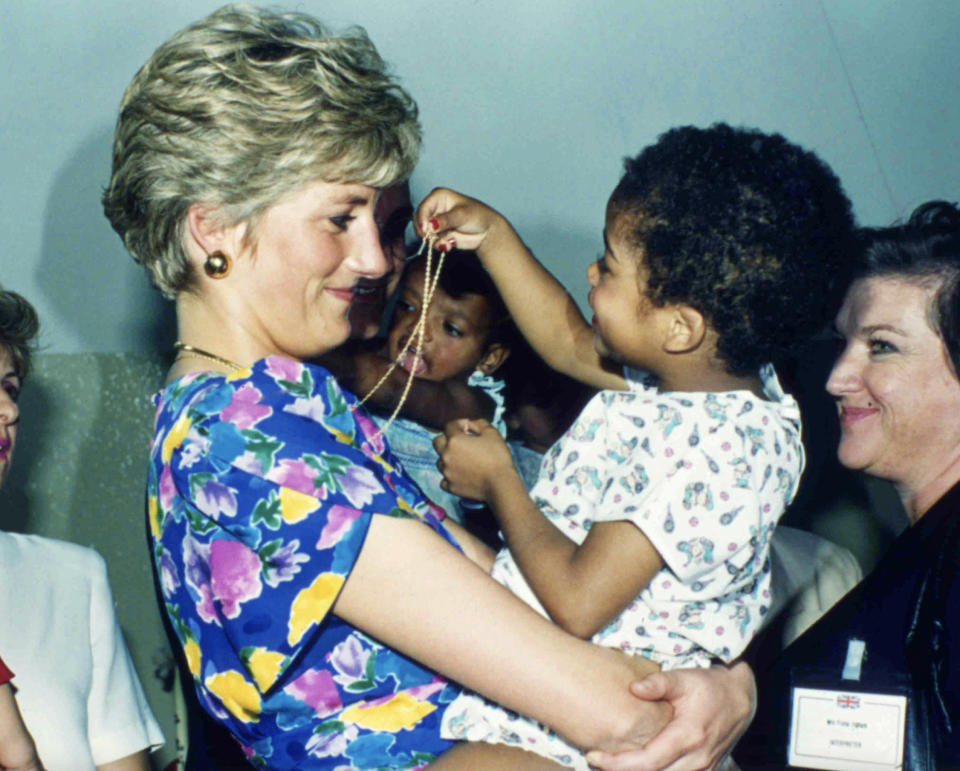

People refused to even touch a person with AIDS because of fear that the illness could be transmitted through a simple touch. Diana, Princess of Wales, worked to break down that stigma. She deliberately went ungloved and shook hands with 10 HIV-positive men in an English hospital in April 1987. The fear — even from the patients — was so intense that only one man allowed himself to be photographed shaking hands with her, and even then, he would not allow his face to be shown. In 1989, she went to Harlem Hospital’s AIDS unit, picked up infected children and hugged them tightly. She helped dissipate some of the fear that permeated the community.

“In our opinion, Diana was the foremost ambassador for AIDS awareness on the planet and no one can fill her shoes in terms of the work she did,” the National AIDS Trust’s Gavin Hart told the BBC in the days following her fatal car accident.

Related

What is HIV/AIDS?

HIV, or human immunodeficiency virus, is a retrovirus that attacks the body’s immune system. It differs from the types of viruses that cause colds and the flu, and attacks T helper cells, the cells that normally help protect us from disease. It is very efficient at tricking host cells to make multiple copies of itself and once acquired, will cause a lifelong infection.

AIDS, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, is the most severe stage of HIV. People with AIDS have badly damaged immune systems and develop a variety of opportunistic infections, and a CD4 cell count (a type of white blood cells) below 200 cells per cubic millimeter of blood. According to the Mayo Clinic, untreated HIV typically turns into AIDS in eight to 10 years. With treatment, the HIV infection may never lead to AIDS.

Treatment

After identifying the HIV virus in 1983, researchers began a rapid search for treatments that worked. In 1987, after my uncle was already dead, zidovudine, also called azidothymidine, or AZT, was approved for use. AZT is not a cure, but it prevents the HIV virus from replicating itself. It is also a difficult regimen to manage, requiring 4-5 pills every four hours, with severe side effects, including some that could be deadly. At the time, it was also the most expensive prescription drug in history, with a one-year price tag of close to $10,000 ($20,000 in today’s dollars).

Scientists kept working. In 1995, the FDA approved saquinavir, an antiretroviral drug that was the first of a new class of drugs: protease inhibitors. Like AZT, it prevents the virus from copying itself, but at a different stage of infection. In 1996, a third medication was approved for use, in another class of antiretrovirals. These three types of medications began to be used in combination and marked the year (1996) that “people stopped dying.”

However, the drug “cocktail” still involved multiple pills per day. Just one year later, 1997, “Combivir” appeared on the market, the first to combine multiple drug treatments into one pill. Today, there are 23 FDA-approved combination medications used to treat HIV. On the one-pill-per-day regimen, patients are more likely to stick with their treatments and less likely to end up sick enough to require hospitalization.

In 1989, Samuel Broder, then head of the National Cancer Institute, declared in a speech at the international AIDS meeting in Montreal, Quebec, that AIDS was a chronic illness and no longer a death sentence — at least for those in the global north.

The end of AIDS

In 2022, AIDS still claimed a life at least every minute of the year, and 1.3 million people became newly infected. Women and girls are still disproportionately affected, and global funding for the fight against AIDS is decreasing.

So how do we get to zero deaths from AIDS in the next 61⁄2 years?

Here are the goals UNAIDS sets out: “95-95-95.” That means that “95% of the people who are living with HIV know their HIV status, 95% of the people who know that they are living with HIV (are) on lifesaving antiretroviral treatment, and 95% of people who are on treatment (are) virally suppressed.”

Five countries have met that standard, and 16 more are close.

“The end of AIDS is an opportunity for a uniquely powerful legacy for today’s leaders,” said Winnie Byanyima, executive director of UNAIDS. “They could be remembered by future generations as those who put a stop to the world’s deadliest pandemic. They could save millions of lives and protect the health of everyone. They could show what leadership can do.”

Ending deaths from AIDS is achievable, but it will take work, political will and funding.

“We are hopeful, but it is not the relaxed optimism that might come if all was heading as it should be. It is, instead, a hope rooted in seeing the opportunity for success, an opportunity that is dependent on action,” said Byanyima.

And, it would be a miracle that was unthinkable for my Uncle Nathan and sweet Carol Zulu.

Holly Richardson is the editor of Utah Policy.