Opinion: Everyone should know the history behind Black History Month. It's applicable today.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s ironic that, amid the celebration of Black History Month, headlines tell of diversity programs being gutted and content that some conservatives find offensive being stripped from Advanced Placement African American history courses.

Predictable backlash against "The 1619 Project" docuseries has hit social media since it first aired Jan. 26. Some Iowans have promised renewed plans to ban critical race theory and prevent "indoctrination" in public schools. On Monday, I listened to mothers, most of whom seemed to belong to the group Moms for Liberty, at the Iowa House Government Oversight Committee meeting. Each had requested that school libraries remove or restrict access to one or more books featuring LGBTQ characters and people of color, books that they deemed pornographic or containing curse words, racist terms or stereotypes.

More by Rachelle:Opinion: The 1619 Project IS patriotic

None of this is new.

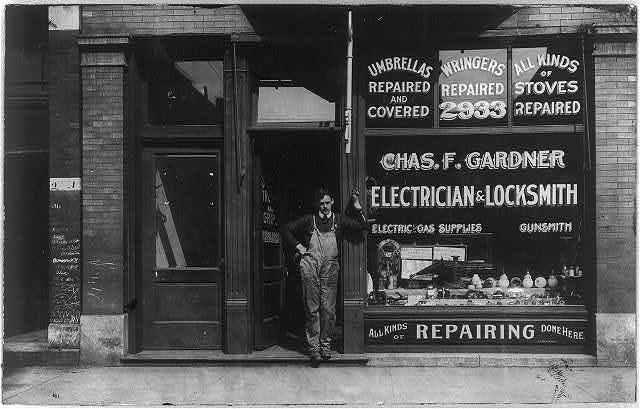

Carter G. Woodson, author of numerous books, founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, and much more, dedicated his life to the promotion and study of Black history. He founded Black History Week in 1926, which became Black History Month in 1976. He published "The Negro in Our History" in 1922.

“The purpose in writing this book,” wrote Woodson, “was to present to the average reader in succinct form the history of the United States as it has been influenced by the presence of the Negro in this country. The aim here is to supply also the need of schools long since desiring such a work in handy form with adequate references for those stimulated to more advanced study.”

Because of the book’s purpose, it was banned.

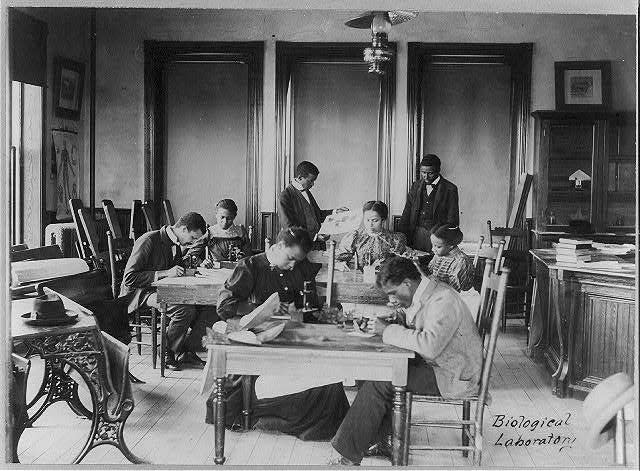

Black teachers risked their jobs, lives to teach Black history

In "Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching," author Jarvis R. Givens shares the story of Tessie McGee, a young Black history teacher in 1933-34 at the only Black secondary school in Parish, Louisiana. McGee, like all teachers, had been instructed by Louisiana’s all-white Department of Education and Parish school board to teach only the approved learning objectives and to keep the approved outline visible on her desk. The state-approved textbook stated, “Not only are almost all of the civilized nations of to-day of the white race, but throughout all the historic ages this race has taken the lead and has been foremost in the world’s progress.”

Of course, McGee wasn't going to teach that. According to a student, McGee would teach from "The Negro in Our History," which she held in her lap. When the principal entered her room, she would teach from the approved outline and book, but when the principal left, she would return to the book in her lap.

Givens shared another example from 1925 in Muskogee, Oklahoma. When the school board discovered that teachers at a Black high school were teaching from Woodson’s book, "they expressed horror and surprise that such a work should have crept into our Negro schools.” They forced the principal to resign, took the book away from teachers, and prohibited them from using it in the future.

Givens noted that the educators knew the punishment could have been more severe. It was believed the Ku Klux Klan controlled the school board. Throughout the country at the time, Black teachers were whipped and lynched, and their houses, Black schools and books were burned.

By 1929, despite the ban — and the danger — "The Negro in Our History" was used in more than 100 Black schools.

White scholars based Black inferiority and white superiority on 'science'

Woodson was adamant that the true contributions and experience of Black Americans be taught from the Black perspective to combat society's and science's negative narrative of the Black race.

More by Rachelle:Opinion: How can Ottumwa schools address racism without admitting racism?

Like all Black Americans, Woodson experienced racism repeatedly. For instance, at Harvard, not only were Black people absent from the curriculum, his doctoral counselor told him that Black people were insignificant in American history and had no history.

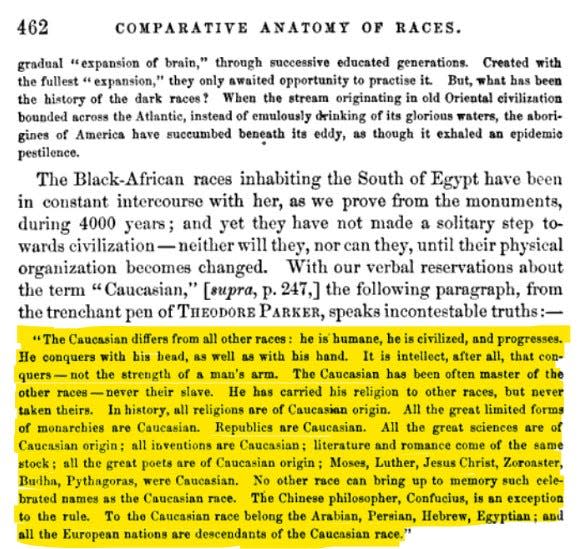

By the 1840s, “science” in the form of polygenesis theory — the belief that different races originated from different species, with white people at the top and associated with the epitome of intelligence and Black people at the bottom most similar to animals — was being used by whites to confirm Blacks' inferiority.

Three men in particular, Samuel George Morton, Josiah Clark Nott, and Louis Agassiz, were known as the American School of ethnology and were leaders in this area. These men, along with three others, wrote "Types of Mankind" in 1854, which claimed to prove white superiority.

Many other books likened Black people to beasts.

These examples of Black Americans as beasts come together in the story of Ota Benga. Benga — “freed” from enslavement in the Congo by Samuel Phillips Verner, who was looking for "African Pygmies" — was exhibited in the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Then, in 1906, he was locked in a cage with an orangutan in the Monkey House for the enjoyment of those visiting New York’s Bronx Zoo.

In "Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga," author Pamela Newkirk paints a horrifying picture of what Benga endured, locked outside in the heat while up to 500 people crowded around him, pointing and gasping and laughing daily.

Wrote Newkirk: “Could this caged creature be, many no doubt wondered, the incarnation of one of the characters in best-selling books like Charles Carroll’s 'The Negro a Beast,' published in 1900, or the 'half child, half animal,' described in Thomas Dixon’s 'The Clansman,' published the previous year, ‘whose speech knows no word of love, whose passions, once aroused, are as the fury of the tiger?’ Could he be the missing link, the species bridging man and ape that preoccupied leading scholars?”

Celebration of Black history derided as 'characterized by racial biases'

Again, the negative, racist beliefs about Black people compelled Woodson to refute these claims and share the real history of Black Americans, which was the impetus behind Black History Week, which would showcase what people had learned and would continue sharing throughout the year. Givens reported that more than 80% of Black high schools celebrated Black History Week by 1931.

In 1934, Walter Daykin, a sociologist at the University of Iowa, wrote a critique titled "Nationalism as Expressed in Negro History" for a prominent sociological journal. Givens quoted Daykin: "'Negroes are urged to appeal to boards of education for the adoption of Negro history text books, or to induce libraries and schools to purchase Negro literature and pictures of notable men.' But all the scholarship produced by Woodson and other scholars involved in this movement were 'compiling data in order to interpret world history from a racial point of view. These historians are partisan, and often record data with the conscious purpose of gaining converts to the Negro's cause.' Daykin argued that 'Negro historical writings are further characterized by racial biases, moralizations, and rationalizations.'"

Echoes of Daykin's beliefs can be heard today, including at the beginning of this column.

Rachelle Chase is an author and an opinion columnist at the Des Moines Register. Follow Rachelle at facebook.com/rachelle.chase.author.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Opinion: We can learn from the history behind Black History Month