Opinion: I spent nine years in the NFL. The truth about football is complicated

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s Note: Coy Wire is a CNN Sports Anchor and Correspondent. The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN. The Whole Story with Anderson Cooper “Hard Hits: Can Football Be Safe?” airs on Sunday, September 10 at 8pm ET/PT.

I spent nine years in the NFL. I was knocked unconscious several times. One time, I didn’t remember what happened until I saw it on film the next day. I came away with a titanium plate and four screws in my neck.

On many days, I wake up feeling like I’ve been through a car crash…even though it’s been more than a dozen years since my last snap in the league. Every time I lose my keys, I wonder, “Did I get hit one too many times?” I pray that I’ll still be able to run and play with my wife and our two young daughters for many years to come, and remember those days forever.

Even given all that, I would also never trade the time that I spent on the gridiron. For me, the rewards have far outweighed the risks, and in some ways, I’ve beaten the odds.

The average NFL player’s career is less than four years, according to the NFL Players’ Association. I played more than twice that time and, despite the joint and muscle pain I just described, I feel rather healthy and well.

But there’s no denying that football is a violent game. There’s no shortage of football critics who point out the ethical questions involved in playing such a dangerous game.

Some very scary injuries in the NFL last season — particularly Damar Hamlin’s experience and Tua Tagovailoa’s multiple concussions — reminded us viscerally of those dangers. Understandably, whenever there’s a high-profile injury, there is a new chorus of voices decrying football and a new cohort of parents who question whether they should let their kids play the sport.

That reaction has always bothered me. Football was my first love. It is America’s most popular sport. Playing it teaches the values of hard work, discipline, sacrifice and teamwork — and I would argue that there isn’t a time when America is more communally engaged than on NFL Sundays with people from different races, religions and socio-economic backgrounds coming together to celebrate a common bond.

Those who insist the game is dangerous aren’t wrong, but that’s not the end of the story. Reporting for the CNN Original documentary “Hard Hits: Can Football Be Safe?” gave me a chance to dig into some of the answers that parents, players, and fans have been searching for. I’m passionate about learning the evolution of the game: where it has come from, where it is, and where it could possibly go in regard to player safety.

But no matter how many rule changes are made, can football ever really be safe? The answer is no, it can’t. But the effort to make the game safer matters a great deal.

Ultimately, amid welcome developments and innovations in better equipment and injury data collection, the most poignant change I’ve seen has been in the culture of football. That gladiatorial, win-at-all-costs mentality, the take-you-out-on-a-stretcher culture that permeated the game for decades seems to be changing for the better.

A night that may have changed everything

A lot of that change can be observed in what happened on January 2, 2023, during a Monday Night Football matchup between the Buffalo Bills and the Cincinnati Bengals.

As players, in the past, we were conditioned to compartmentalize pain — our own and others’ — both physical and mental. We learned not to focus on the negative because it can hinder optimal performance. We were trained to fight on with a “next play” mentality anytime something bad happened. So, playing on, despite tragic injuries and ambulances rushing players off to the hospital, was all we knew.

But something powerful beyond measure happened when Damar Hamlin went down, unresponsive, and the game was called off.

The decision to call off a game in progress was not only unprecedented, but it also represented a paradigm shift that’s happening within the NFL regarding player health and safety. No longer, perhaps, are we in the barbaric days of looking at players as disposable, replaceable pieces of meat.

In my playing days, that game would have never been called off. Coaches and players alike would’ve likely said, “Alright fellas, buckle up and get back on that field. It’s time to play.” I was on the field two separate times to witness a player get paralyzed, only to have the game continue as if nothing happened moments later. One instance happened while I was playing at Stanford. The other was in 2007 while playing for the Buffalo Bills.

At the time, my now-wife asked, “Why did you guys do that?” I asked her, “Do what?” She pressed, “Why do you guys keep playing after someone is paralyzed?” And I responded without skipping a beat, “Well, of course we do. That’s what we always do.”

So, in 2023, we can’t overstate how impactful it was for the head coach of the Buffalo Bills, Sean McDermott, to lead the way and for the players and league to agree, to make the decision to end that game.

It was a profound decision where the health and wellness of the players was truly prioritized over the outcome of a game or season.

And the rest of the NFL was watching. College coaches, high school and youth coaches, and parents were watching, too. Some day we may look back and see that this was the moment where it all changed — where statements about the importance of player safety no longer rang hollow, and it became clear that putting players’ health, both mental and physical, first truly is the right thing to do.

Before Hamlin’s injury, no NFL games had ever been called off mid-game due to an injury. Now, there have been two NFL preseason games that were stopped mid-game because players were carted off the field.

A violent history

Despite these culture shifts, football is a violent game — and always has been.

In 1894, for example, the Harvard-Yale football rivalry was cancelled for two years after a game so gory it was named “the bloodbath at Hampden Park.”

By 1900, America’s gridirons routinely became routes to burial grounds. The game looked more like rugby; the forward pass was illegal, so players locked arms and became like human battering rams, brutalizing each other with hardly any protection, not even a helmet.

In 1905, there were 19 football deaths and hundreds of severe injuries, according to Jon Kendle, Vice President of Museum and Archives at the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. While President Theodore Roosevelt even publicly proclaimed his affinity for “rough, manly sports” and what it could teach young men. But even he could not ignore the expanding body count…especially when his own son, Ted Jr. was seriously injured while playing for Harvard.

In late 1905, President Roosevelt called a summit of Ivy League coaches and others to figure out how to make the game less brutal.

Sound familiar?

Some of the rule changes that emerged from that meeting were the legalization of the forward pass and a change to the line of scrimmage that allowed for the game to open up and spread out, thereby making the game safer.

What comes next

Professional football players today are well aware of the risks involved in choosing to play. Early in my career, we had no idea about chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the progressive and fatal brain disease associated with repeated blows to the head that a number of football players have been found, posthumously, to have been suffering from. Education has been key to this growing awareness. Some of my most profound learning experiences have been seeing older, former players trying to walk… or stand up… it’s really sad and eye-opening.

This summer, the Concussion Legacy Foundation and Boston University’s CTE Center’s most recent research found that nearly 92% of 376 former NFL players whose brains were studied were diagnosed with the brain disease. The families who donated the players’ brains likely already suspected CTE in their loved ones. CTE can cause changes to the brain and manifest in a variety of symptoms including memory loss, confusion, aggression, depression and even proneness to consider suicide.

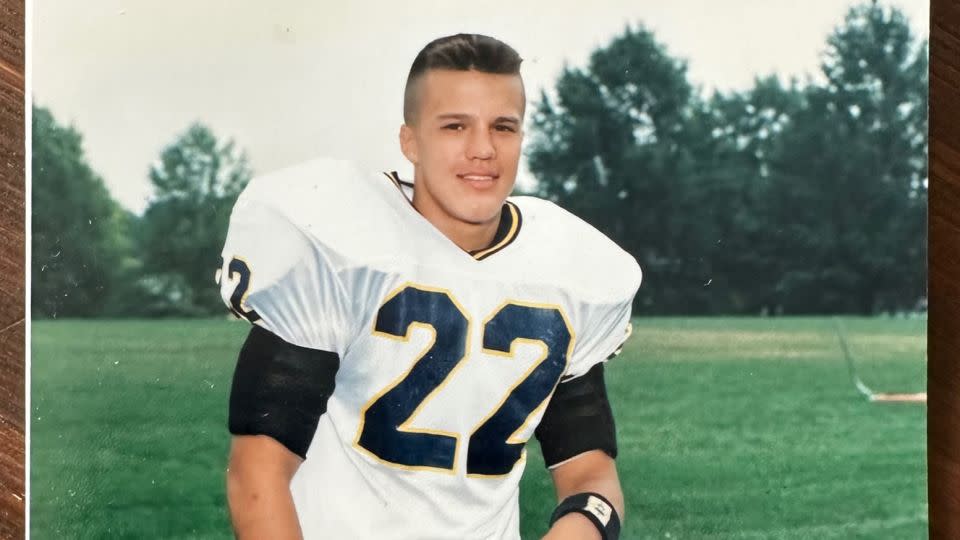

As part of the documentary, I visited the football team at my alma mater, Cedar Cliff High School. I remember how inspired I was when NFL player Kyle Brady came back to speak to me and my football teammates when I was in high school. He was a first-round draft pick to the New York Jets. I wanted to be like him. I found a picture of Kyle on stage at the NFL draft. I took that picture, and I taped it on my ceiling above my bed so that it was the first thing I saw every morning and last thing I saw before I went to bed at night. It was a constant reminder of my dream to make it to the NFL.

I became a machine. I’m talking 100 sit-ups every morning as soon as I got out of bed, 100 sit ups before I went to bed at night. I started eating for purpose, not for pleasure. I went on to earn a football scholarship to Stanford University. Eventually, in 2002, that dream came true, and I was drafted to the Buffalo Bills.

My parents were a huge part of my achieving that dream. They sacrificed time and money. They helped me train. They kept a journal of my workouts. They took me to the park to do drills using plastic plant pots as cones. My mom even went to the junkyard and cut out old seatbelts, sewed them into a harness and attached old tires to it so I could run while towing the weight behind me.

But my dad did surprise me recently when he told me this: If they had to do it all over again, knowing what we know now about brain injury, he would have preferred that I played flag football until age 12 or 13. In fact, flag football—a version of the game without full contact— is on the rise in kids ages 12 and under.

My dad isn’t alone; a number of legendary former players have expressed concern about the young people in their lives playing tackle football, including Bo Jackson, Harry Carson, Mike Ditka, Troy Aikman and Brett Favre. Those players who’ve come out and said that they wouldn’t play the game or that they wouldn’t let their children or grandchildren play the game are completely justified in their thinking. Football is not a game for everybody.

And yet: Our research and reporting for this documentary show that the game is safer than it has ever been. And the way the NFL takes care of players today has a trickle-down effect at the collegiate and high school levels. All 50 states have some kind of concussion protocol in schools now. Many states are requiring that defibrillators and trainers be present at all football games.

Football isn’t safe, but it’s safer, now that we are having many more, and deeper, conversations about the future of America’s most popular sport.

With reporting by CNN Documentary Producer A. Chris Gajilan.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com