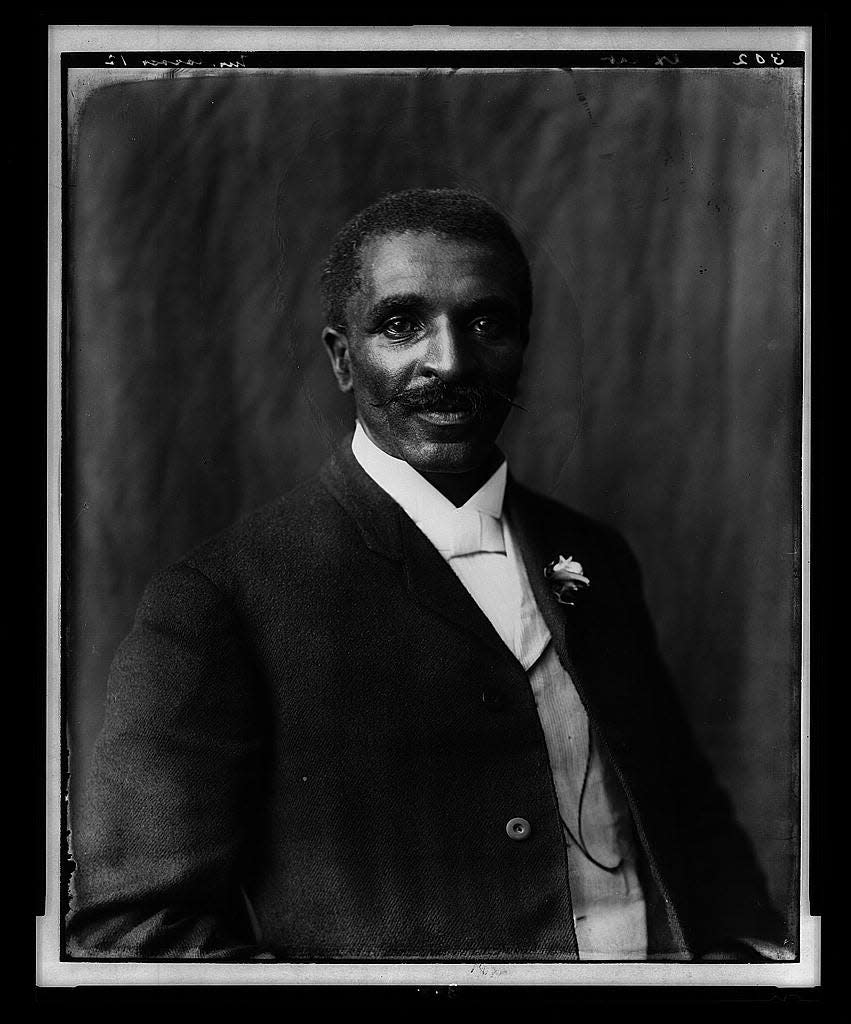

Opinion: George Washington Carver exemplified Black excellence despite suffering

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“I love to think of nature as an unlimited broadcasting station through which God speaks to us ...” — George Washington Carver

The words bring to mind myriad encounters during my nature walks. But this column is not about me. It is about Carver.

Carver came into the world Black. His Black mother, his Black body, and even his last name belonged to a white man. In spite of being dealt such a harsh card, Carver became the first African American to earn a bachelor of science degree. The first African American to attend Iowa State University.

Carver was known even by icons. Booker T. Washington, Henry Ford, Mahatma Gandhi all knew him. Time Magazine named him “Black Leonardo” for his art skills. Some think Carver belongs with legends like Martin Luther King Jr., W.E.B. Du Bois, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass.

Carver was an adviser to U.S. presidents. Kudos to FDR for ordering a national monument to be built in Carver’s honor. An honor once reserved for presidents.

Carver mentored a young Henry A. Wallace, who became an Iowa icon. Kudos to Iowa for declaring Feb. 1 George Washington Carver Day.

Inside his farming demonstration lab at Tuskegee, I can picture Carver nodding in agreement to a statement in President William Taft's 1908 acceptance speech: “As the Republican platform says, the welfare of the farmer is vital to that of the whole country.” Very true. Farmers were essential in 20th-century agriculture, as they had been in the Fertile Crescent 10,000 years ago.

But Carver must have also known that Black American farmers were not doing well. Between 1910 and 1997, Black farmers lost 90% of their land. Their numbers as a proportion of all farmers declined from about 14% in the 1900s to less than 2% in 2020.

The decline in the percentage of Black American farmers is a product of longstanding institutionalized racism. Even the United States Department of Agriculture refused to process loans for Black farmers. A group of Black farmers sued the government last year for reversing its promise to fix the wrongs after a group of white farmers decried reverse discrimination.

Carver lived in dangerous times. I can imagine his incredulity when he heard Taft say further in his 1908 speech: “The Republican platform … explicitly demands justice for all men without regard to race or color.” Yet, that same year, in Springfield, Illinois, a Black man was accused of assaulting a white woman. Even though the accusation turned out to be untrue, a race riot ensued. Homes were torched, a couple of elderly Black persons were lynched.

If Carver were here today, he might still insist: “The road to achievement has no shortcuts.” I agree. There are no shortcuts to true equality. Achieving true equality starts with our admission that inequity in agriculture was exacerbated even by President Abraham Lincoln. He signed the Homestead Act of 1862 to increase land ownership by U.S. citizens, yet only white Americans were considered citizens then. Black Americans became citizens in 1868 after the 14th Amendment was ratified. Native Americans became citizens in 1924 after the Indian Citizenship Act was passed.

During my 20 years of employment at predominantly white universities (PWIs), I have listened to many talks about a need to increase the number of Black students in agriculture. The intention is good. After all, many PWIs once kept their doors shut to Black students. But what is frequently missed in these talks is how to retain students of color in a discipline born out of injustice. Some still fail to realize that past injustices contribute to negative perception of agriculture by students of color.

Did Carver have a choice to be in agriculture? That’s a tough question. But if Carver were here to answer, he might say: “The more information one has, the greater will be the inspiration.”

This is Carver’s call for all Americans to support the teaching of the entire history of this country. We cannot inspire our children to fight injustice if we prevent them from learning what happened to Carver’s forebears.

Carver might also say: “Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom.” Very true. The door to freedom is what every human seeks. To be free is to be in spaces devoid of racism, something Carver did not enjoy even after he became famous.

But Carver was special. He saw God’s love in nature. He saw God’s love in Black and White hearts.

“How far you go in life depends on your being tender with the young, compassionate with the aged, sympathetic with the striving and tolerant of the weak and strong, because someday in your life you will have been all of these.” These are words that epitomize Carver’s life.

Some named Carver “a peanut man.” But Carver was more than peanuts. The name Carver invokes his spirit, the spirit of Black excellence.

Walter Suza of Ames, Iowa, writes frequently on the intersections of spirituality, anti-racism and social justice. He can be contacted at wsuza2020@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Ames Tribune: Opinion: George Washington Carver — Black excellence amid suffering