Opinion: Holocaust survivor Max Glauben’s message, as antisemitism spikes: We must be 'Upstanders'

When I began chronicling Holocaust survivor Max Glauben’s biography, I struggled to imagine a childhood so haunted by hatred. What Max first experienced as rock-throwing and name-calling reached a crescendo with the systematic murder of 6 million Jews. Max’s entire family was killed when he was 15. Such potent hatred felt distant from my experience growing up Jewish in America.

As I continued researching for "The Upstander," I was startled to hear from Max’s wife, Frieda, that she, too, had been the target of name-calling and rock-throwing – in Dallas, Texas. “Dirty Jew!” children yelled at Frieda and her friends as they chased her home from school in her youth.

“I just thought it was natural” that people throw rocks at Jews, Frieda told me from her dining room table in the city we both grew up in.

I thanked God I had not personally seen such unabashed hatred toward my community in my lifetime. But now?

Staggering data on antisemitic assaults

Though Jews make up less than 2% of the United States population, 60.3% of anti-religious hate crimes in 2019 targeted the Jewish community, per FBI data. Assaults against the Jewish community spiked 56% from 2018 to 2019, the Anti-Defamation League reported. The 2,107 total incidents of antisemitism, including a fatal synagogue shooting for the second straight year, marked the most on record in 40 years of the ADL’s annual Audit of Antisemitic Incidents.

Even more recently, following the conflict escalation between Israel and Hamas this May, 60% of American Jews personally witnessed antisemitic behavior or comments, according to an ADL survey. Seventy-seven percent were more concerned about antisemitism in America because of the recent violence and 41% were more concerned about their personal safety.

The data is staggering.

How can the country in which I actively embrace and openly discuss my religious heritage while working for a national publication simultaneously harbor the hatred that fueled the vandalism of my mentor’s Maryland synagogue? Jews have been violently attacked, including on the streets of Los Angeles and New York City in May 2021, while wearing a religious skullcap – the same skullcap my brother wears proudly to school and work.

I think back to the injustices Max’s family first faced and how, within five years of similar assaults, he and his family were forcibly transported to mass killing centers.

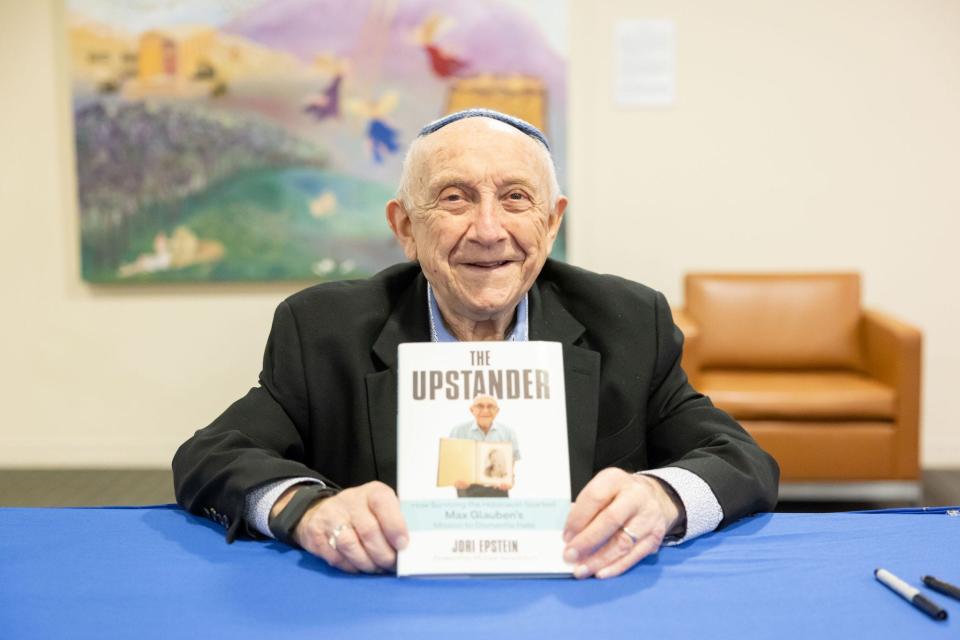

Max’s memoir, "The Upstander," emphasizes a grim truth he witnessed during the Holocaust: Simply refraining from hate is insufficient. We do not have the luxury to remain bystanders.

“Hatred,” Max told USA TODAY, “cannot be eradicated without doing something about it.”

USA TODAY Opinion in your inbox: Subscribe to our newsletter for more insights and analysis.

‘The problem with hate’

Antisemitism, as hatred toward Jews is called, has infiltrated society throughout history. The Jewish community has enjoyed periods of relative freedom and security; but at best, hatred toward Jews seems to fester beneath the surface.

For Max and his family, the consequences were devastating.

When Max was 11 in Warsaw, Poland, he could no longer visit his father at work without neighborhood children physically and verbally abusing him because he is Jewish. That same year, in 1939, the Nazis burned his father’s newspaper office to the ground. Jews were banned from schools and professions, Max and his family crammed into a confined ghetto area. They were allowed rations amounting to just 184 calories per person per day – the rough equivalent of two apples.

Armed guards at my Jewish preschool: Why is antisemitism never a crisis in America?

In May 1943, Max, his brother, his mother and his father were deported to Majdanek death camp. Within three weeks, Max’s entire family was killed. Max survived six horrific concentration camps as an airplane factory laborer.

“We looked out the window and the skies were blue and there weren’t too many clouds in the sky,” Max remembers thinking from the boxcar hauling his family to the death camp. “‘Why? For not doing anything, why did it happen to us? Where are we going?’ Everybody was asking, but I don’t think anybody knew the answer.”

Eight decades later, answers still elude us.

Hate, then and now, defies logic.

But we cannot allow its incomprehensibility to paralyze us into inaction. We can’t afford to view Max’s testimony as a problem solved or unsolvable. No, the 93-year-old says: His history is real, recent and relevant. If humanity was capable of this then, we cannot assume that has changed.

Conquering extremism: We can fight hate in our communities before it escalates to violent crime and extremism

Max, who has devoted the last forty years of his life to unmasking the perils of hate and the routes to tolerance, embraces the term “upstander.” We owe it to ourselves and our communities to not stand idly by when hate speech and actions intensify. We must speak and act with regard for the consequences. We must examine our behaviors and biases.

“The problem with hate is that it (grows) within an individual,” Max said. “I sometimes compare it to yeast, when you bake a bread. You put a little in there and have a little water and flour, put it in the refrigerator and it overflows.

“That’s how hate does inside of a hater.”

Preserving Max’s testimony

Education is a key tool to combating hatred toward Jews.

I was 17 years old when I first visited the Nazi death camps of Majdanek, Auschwitz, Birkenau and Treblinka with Max. His testimony elicited far more questions than answers.

The history I bore witness to engulfed me.

A life's purpose: 75 years ago, this Holocaust survivor reclaimed life. Now he works to erase hate.

How, I wondered from the death camp where Max’s mother and brother were murdered, could humanity let this happen? How could Max, guiding us stolidly through these death-stained musty barracks, still resoundingly embrace resilience and compel tolerance?

“I have a lot of information in me,” Max said. “Should I, after realizing how I can help to make this a better world, be gone with that information? Or should I expose what happened to me? Show people each one of us can be an upstander and treat everyone the way they like to be treated.”

We began "The Upstander" four years later, in 2016.

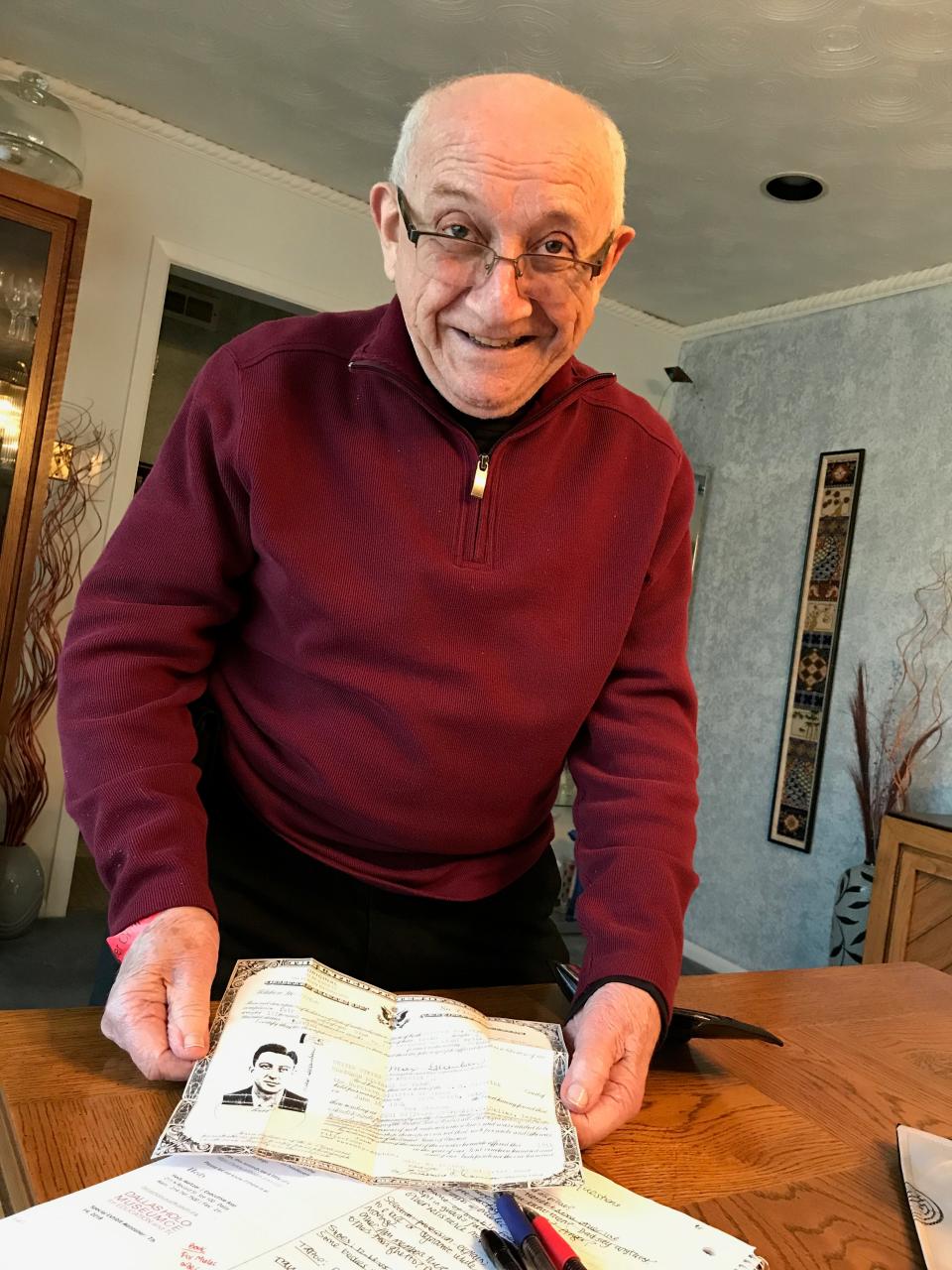

Max and I have since pored over his oral histories and the meticulous documentation of his enslavement: camp transfer notation, displaced-person arrangements, immigration correspondence and social-services case reports. We returned together to Warsaw and four concentration camps in 2017, unleashing crucial recollections and emotions from which Max has trained himself to dissociate. Local and national Holocaust museums enabled us to corroborate historical context across sources. Then, we ventured into uncharted territory: the psychological impact the Holocaust imprints on Max and his family through present day.

The Holocaust and hatred are no more comprehensible to me today than they were when I first toured the concentration camps at 17 years old.

But I am committed – and hope you, our readers, are too – to the continual pursuit of grappling with humanity’s capacity for hatred and violence.

We must continue to confront history such as Max’s life to better understand the depth to which humanity can sink and, in concert, the immense potential each of us has to stand up for what’s right. We must not only remember the Holocaust, but also inspire tolerance education and action. We must deepen the love and shared understanding between and among diverse communities before it is too late. Please: Join us to thwart hatred toward the Jewish community. Let’s begin by educating ourselves.

“If you have any hatred, bigotry, or antisemitism,” Max says of The Upstander, “I hope that after you read this book, you might change your mind.”

Max wants you to know that he believes in the difference that you – yes, you – can make on the front lines fighting hate. His reflections underscore that heroism emerges not when we hold ourselves to superhuman standards, but rather when we let our humanity prevail.

“Life is like the stock market,” Max smiled through his thickly-accented English in conversation. “It goes up and down and up and down. Always do the best you can with what you got.

“And never, never, never, never, never, never give up.”

Jori Epstein is an NFL reporter for USA Today and the author of Holocaust survivor Max Glauben’s memoir, The Upstander.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Holocaust survivor’s message as antisemitism spikes: Be 'Upstanders'