Opinion: Why I changed my mind about the US Senate’s relaxed dress code

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s Note: Elena Sheppard is a culture writer who focuses on books, fashion, theater and history. Her first book, “The Eternal Forest: A Memoir of the Cuban Diaspora” is forthcoming from St. Martin’s Press. The views expressed here are her own. View more opinion on CNN.

This essay has been updated to reflect news developments.

Earlier this month, we learned that the US Senate’s 100 members will no longer needed to adhere to their business casual dress code. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said in a statement that, “There has been an informal dress code that was enforced.” He added that now, “Senators are able to choose what they wear on the Senate floor. I will continue to wear a suit.”

Initially, I pearl clutched a bit. The thought of no dress code in the Senate sent me into a spiral on the idea of decorum. I imagined a Senate floor littered with people in sweatpants and cut-offs, which I just knew would undermine the seriousness of their work.

I imagined elected officials milling around in cargo shorts and Carhartt sweatshirts — aka what Sen. John Fetterman calls “Western PA business casual” — or wearing their pajamas to a vote. I thought about how this green light to dress down would devalue the importance of this legislative body and their responsibility to American citizens.

And then I realized my worries made no sense. Style is ever-changing, politics are ever-evolving and attire getting more casual is an age-old complaint. When we think about a choice like the change to a dress code it’s important to see it in its larger context. Unfortunately, the rest of the Senate wasn’t able to do so. The chamber passed a resolution Wednesday formalizing business attire as the proper dress code while on the Senate floor.

Yet over the years, other dress code relaxations have occurred in the Senate without disaster. In 1993 female senators were — at last — permitted to wear pants on the Senate floor. In 2019 the Senate finally stopped enforcing a rule that prohibited female senators from baring their shoulders.

That dress codes have been used to feminize, and disempower, women throughout history is news to no one. A look at images of the Senate over the years shows the evolving fashion for male senators too — from waistcoats and tails in the early 19th century to suits and ties in the early 21st.

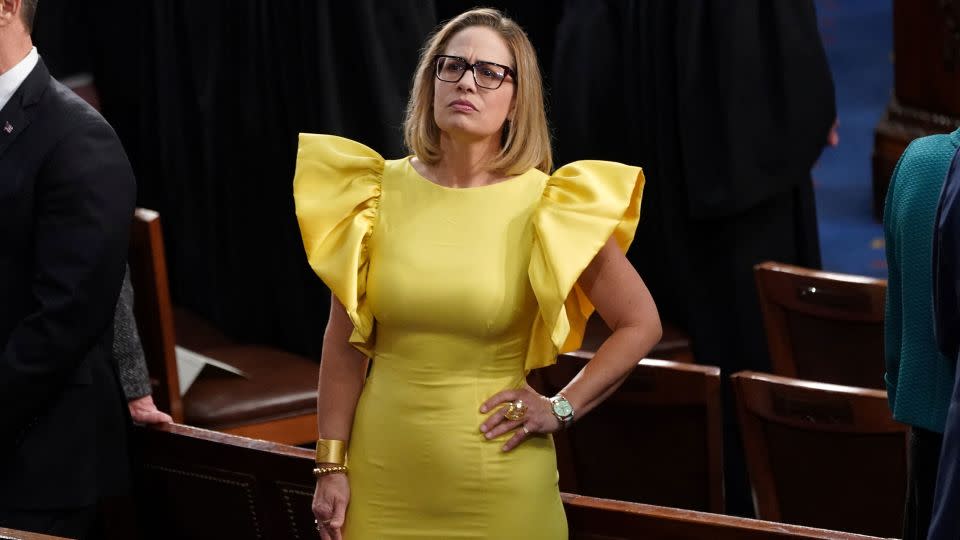

There are recent instances we can point to when senators have cast votes in far more casual attire than that. Sen. Ted Cruz once cast a vote in basketball shorts and sneakers, former Sen. Richard Burr was famous for never wearing socks. And then of course there’s Sen. Krysten Sinema, whose loud sense of style has launched many an article.

These choices are political as much as they are sartorial. Sinema, for instance, transmits through her clothes that she is an individual and independent, which also reflects her party affiliation: Independent. Fetterman, in his Carhartt and shorts, evokes his truth as a man of the people.

Historically speaking, dress codes are a way of marking social hierarchy and, with respect to politics, have always been a way of making a statement. When George Washington was inaugurated in 1789 he wore a “plain brown woolen suit of American manufacture” — the choice a clear rebuke of the aristocratic British traditions from which his new nation had successfully revolted. His suit, simply put, was a political choice.

In our current political landscape, politicians of color have spoken out about how dress codes do not reflect their identities and, in fact, force them to conform to a White man’s version of decorum. In 2021, Rhode Island state senator Jonathan Acosta, who is Hispanic, spoke out about a proposed dress code in the Senate calling it an act of “oppression.” “White collar, white people,” he said at the time, noting he prefers not to wear a blazer and tie. He added that by dressing in that expected uniform he, “came to realize what I was doing was reaffirming to all the Black and brown poor kids that I was teaching that, in order to be successful, you had to try to look and approximate whiteness as much as possible.”

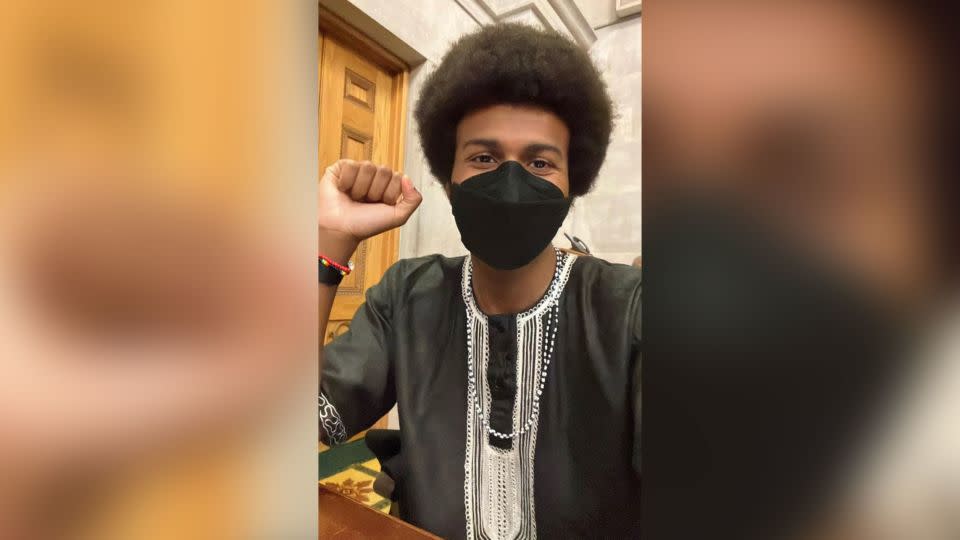

Earlier this year in Tennessee, State Representative Justin J. Pearson was reprimanded by his fellow lawmakers for wearing a dashiki, a traditional West African garment. On the other side of the world in New Zealand, a Maori leader was removed from parliament for refusing to wear a tie, which he called a “colonial noose.”

Dress codes are late to account for these differences of tradition, custom and identity. Generally speaking, they enforce a standard of Whiteness; a conformity that comforts those traditionally in charge.

The change to the Senate dress code earlier in September was predictably met with outcry, mostly by Republican lawmakers. A letter sent to Sen. Schumer, led by Sen. Rick Scott of Florida and signed by 46 Republican senators, urged him to “immediately reverse this misguided action.”

Sen. Roger Marshall of Kansas called it, “a sad day in the Senate.” Sen. John Cornyn of Texas deemed it another example of Schumer’s doing “everything he can to destroy the traditions of the Senate.” Sen. Cynthia Lummis of Wyoming said that “people who dress like slobs tend to think they can act like slobs.” Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, who shouted “liar” at President Biden during the February State of the Union, called it “disgraceful.” The question I found myself asking when reading these responses was, according to whom?

While it wouldn’t be my express preference for all senators to sport their most casual ensembles on the floor, the realization I came to is that my express preference doesn’t really matter. Politicians are in the image business and are very well aware that clothing sends a message.

If a member of the Senate wants to wear a suit, great. If they choose a dashiki, that’s great too. A dress? I’m all for it. I’m sorry that the new resolution denies them the full breadth of that choice.

Largely speaking, if what the senators are wearing is our top concern then we are certainly not focusing on the most important parts of their jobs. As voters, we have put our trust in these people to have a large say in both the present and the future of our country. What exactly are we saying if we don’t trust them to pick out the clothes they want to wear to work?

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com