Opinion: Kids should not face the nearly unsurmountable barriers thrown in my dad's path.

Jill Sell is a freelance journalist, essayist and poet in Sagamore Hills in Summit County. She currently uses a walking cane and is grateful for those parking spaces for those with disabilities.

The college treasurer’s office was in an imposing stone building set upon a hill, shaded by mature oak trees where black squirrels played. Although it was part of state university campus in Ohio, the building reminded me of one belonging to an elite, historic Ivy League women’s college.

Wide, uneven stone steps led from the curving driveway in front of the building, the only place visitors were allowed to park. I loved the building, the steps and the future that awaited me. But in my excitement, I forgot about my father.

This guest column is available free:Support the exchange of local and state ideas by subscribing to the Columbus Dispatch.

My father was born in this country, but contracted polio when he was 3 years old. My grandparents took him back to what was then called Czechoslovakia to be “cured” by the Old World country’s healing waters.

More:Some 200 years ago, disease hit Columbus area hard

When that didn’t work, they returned and were detained for a while at Ellis Island even though my father and his parents were American citizens. My father had his little brown crutches taken from him and he had to crawl to his mother to prove he was physically fit enough to enter this country.

But that’s another story.

In 1968, at the college I hoped to attend, my father looked up at what seemed unsurmountable stairs for anyone with crutches. No railings to hold onto, no accessibility ramp, no preferred parking for those with disabilities.

I froze.

How was my father going to do this? I selfishly began to fear that we would miss my appointment with the financial aid counselor and my college career would be over before it started.

My father had encountered barriers like this all his life, although not quite as daunting. He was not about to let his daughter miss out a college education, an opportunity he was denied, but certainly deserved.

He placed one crutch on a step at a time and pulled his leg up using a hand behind his knee.

He basically hopped up the hard, dangerous stone stairs. Repeating this action 15, 20 times he reached the top. Any doubts that my father loved me before that day were erased.

My father died before I completed the first quarter of my freshman year. But I kept climbing, partially for him.

He would be amazed at how many physical barriers been removed for people with disabilities. Many dangers have been replaced or altered with improvements, including reserved parking spaces for those with disabilities, something we take for granted now.

But I have read recently concerns about the reemergence of polio (poliovirus). Once nearly eradicated, polio has again been found in New York, London and other world cities in 2022. (“Global Implications of polio in the United States in 2022”; www.idsociety.org.). And that’s troubling.

Opinion:'We see all of you.' People with disabilities not 'forgotten' through COVID-19

“While there is no cure for polio, most people recover without long-lasting damage (but) muscle weakness or paralysis can be permanent,” according to The Cleveland Clinic.

Health experts say today not all children and adults are vaccinated against the disease that paralyzed more than 21,000 people in the United States, most of them children, in the country’s last major outbreak in 1952, as noted by The Cleveland Clinic.

Covid has put us behind on routine vaccines, some parents are fearful of more vaccines and our global society has made polio easier to spread. I do not want it to be part of anyone’s life.

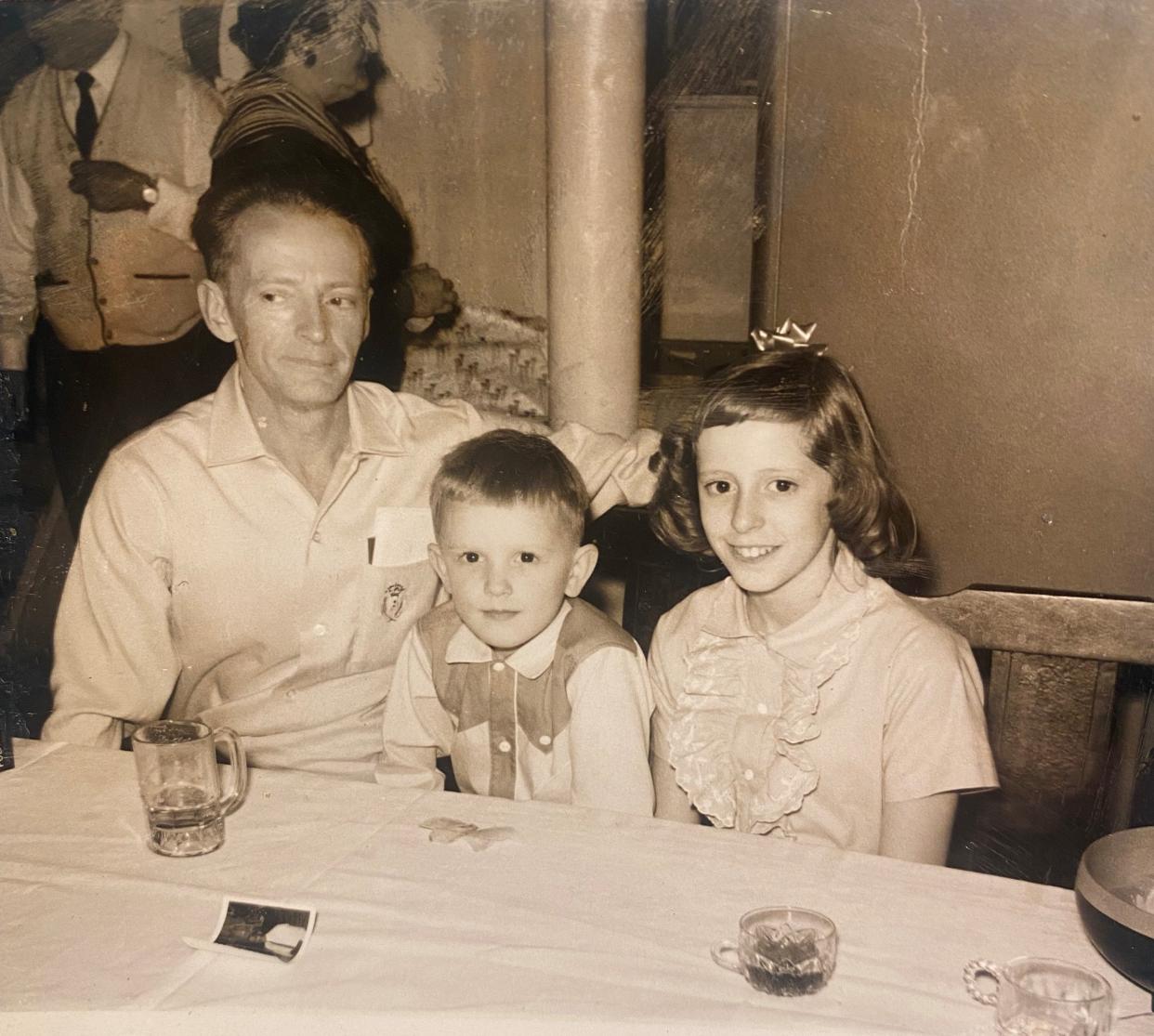

My father was always the pitcher when the neighborhood got together to play baseball. It never occurred to me until years later that was because he couldn’t run the bases. But little else stopped him.

He invented a nifty little device to use the floor-mounted high beam light switch in his car, created metal grippers for his rubber crutch tips so he was safer navigating on slippery icy sidewalks and was a gifted photographer all his life, strapping a camera to his crutch.

More:Will polio spread like COVID-19? Experts say it's unlikely but the unvaccinated are still at risk

Once he spent hours in an iron lung machine to help him breath and was placed head-to-head with another person undergoing the same treatment for polio – Anne Kinder Eaton, wife of Cleveland millionaire industrialist Cyrus Eaton.

The family story goes that Cyrus came to visit his wife in the hospital one day and struck up a conversation with my father. He came back the next day with an almost brand-new pair of shoes that he claimed hurt his feet and figured my father might want them.

I was told my father and Anne got a good secret laugh at that knowing those shoes would hardly ever touch the ground.

Sometimes people in public would come up to my father and talk loudly, assuming because he couldn’t walk without aid, he must have been hearing impaired as well.

He was always gracious and I learned as a child that sharing even informal education about disabilities was better than getting upset, embarrassed or angry.

My father and I, in my own way, learned to cope with his polio.

He was, he believed, luckier than many people whose lives were taken or who were a lot worse because of the disease. I remember standing in line at my elementary school waiting for my turn to receive a little white paper cup containing a sugar cube laced with polio vaccine.

If some kids complained this was taking time away from their play, I wanted to tell them they really didn’t want to miss running through a field, climbing a tree or jumping across a rain puddle. But I didn’t. I was silent.

But now I am not. I urge parents to accept polio vaccines for their children and adults who missed the preventative method as youths to get caught up. You never know when and where there are steep steps to climb.

Jill Sell is a freelance journalist, essayist and poet in Sagamore Hills in Summit County. She currently uses a walking cane and is grateful for those parking spaces for those with disabilities.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: What impact can polio have on families. Why should parent be concerned.