Opinion: 'Muhammad Ali' documentary doesn't shy away from boxer's flaws

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Barely a minute into the documentary “Muhammad Ali,” the tone is evident but doesn’t foreshadow what’s coming next.

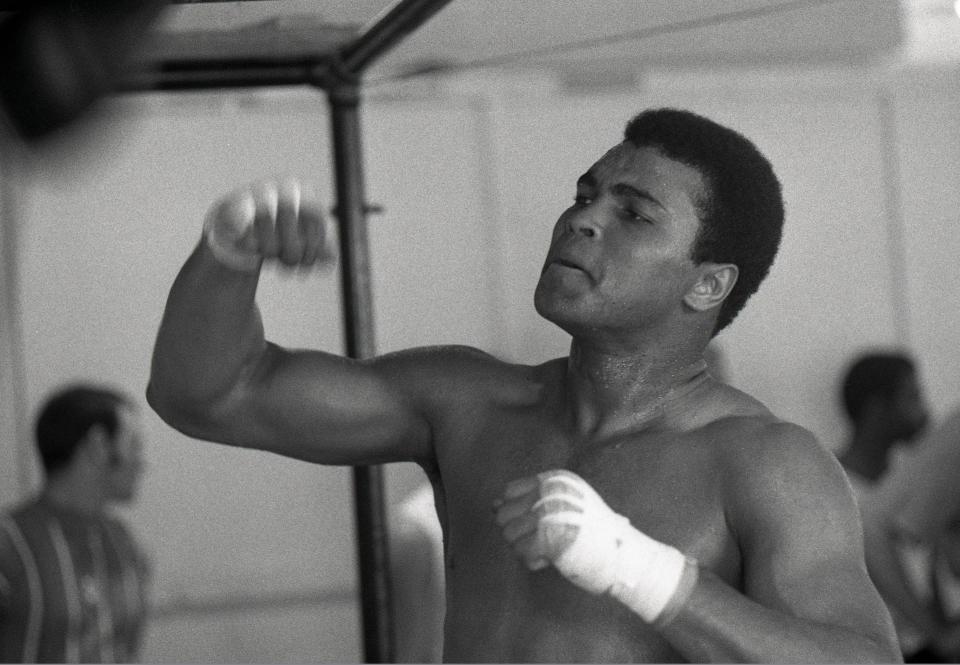

A lighthearted, playful moment as he steals corn flakes from one of his daughters. Jubilant crowds chanting his name. And of course, the brash, braggadocio style of talking (and fighting) that athletes of his generation wouldn’t dare emulate -- or didn’t have the personality or gall to pull off.

“Boo, yell, scream, throw peanuts, but whatever you do, pay to get in,” Ali proclaims at the height of his boxing prowess. (The documentary uses his given name, Cassius Clay, up to the point where he changes it to Muhammad Ali in 1964.)

Ali tells you exactly what you are about to spend nearly eight hours of your life watching: a deep look at society, war, race relations, the role of the Black athlete, the fragile state of religion in America and politics.

This is done through deliberate pacing and a myriad of interviews, including with several family members who give thoughtful, critical analysis. (That analysis was absent in 2019’s “What’s My Name,” which was broadcast on HBO and used archival footage and Ali’s own voice for narration.)

The documentary also commands your attention through the smooth tenor of narrator Keith David and the pulsating soundtrack, which includes music from Jimi Hendrix, Carlos Santana and Bo Diddley. It even mixes hip-hop flavor from Mos Def, along with an outstanding use of Digable Planets’ “Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat)” mixed in scenes showing his fight with Floyd Patterson.

There is no emotional confusion or gray area here. You either love him or hate him, but you can’t keep your eyes off him, whether you agree with his social, religious, and political beliefs or not.

This four-part documentary series, which airs on PBS starting Sunday night (★★★ 1/2; not rated) describes Ali as a man who was “unconditionally himself” and comes from venerable filmmaker Ken Burns ("Baseball," "The Civil War"), with his daughter Sarah Burns and her husband, David McMahon, ("The Central Park Five," "Jackie Robinson," "East Lake Meadows: A Public Housing Story"), who pick up co-directing and writing credits.

KEN BURNS ON ALI: PBS documentary delivers expansive look at boxer's life

Trying to understand a man so complex and complicated is a bold undertaking. Armed with 500 hours of footage, music, along with archival photos, “Muhammad Ali” presents a deep look at the boxer who possessed agility, finesse, a devastating jab with the gift of gab.

But it also comes on the heels of criticism of Burns and PBS concerning diversity and complaints from filmmakers about limited opportunities when it comes to profiling subject, especially people of color. The network and Burns have also been accused of mutual overreliance, alleging both have contributed to a "systemic failure to fulfill (its) mandate for a diversity of voices."

Burns denies those narratives on his own films and says race shouldn't matter when making art, but he does acknowledge the problems that exist in the industry.

The issue with most documentaries, especially when the subject is so well-known and can be easily researched, is finding not only new information to advance the narrative, but presenting it in a way without sounding repetitive, insulting the audience's intelligence with lazy storytelling or trying so hard it lacks nuance or substance.

You will rarely find that problem here, although you do get Burns' signature of zooming in on a photograph. But it’s important to note how accuracy plays a part in telling a complete story.

There is no mention of Ali allegedly throwing the gold medal he won at the 1960 Rome Olympics into a river after being refused service at a restaurant. The filmmakers said that footnote could not be conclusively verified to their satisfaction. (Ali received a replacement medal at the 1996 games in Atlanta.)

The origins of Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.’s humble beginnings in the segregated Jim Crow South of Louisville, Kentucky, are in the oft-told story about his stolen bike. When he was 12, the new bike he shared with his brother, Rudy, was stolen. But that event led to him taking an interest in boxing.

A man of incredible depth, thoughtfulness and an oratory style his own, Ali was a man, at first glance, of glaring contradictions: He wanted racial equality and fought, at the cost of his livelihood, against an unpopular war in Vietnam. But he also used racist language to disparage and embarrass some Black opponents, namely Patterson, Ernie Terrell and most famously, Joe Frazier.

His faith was based primarily on teachings by Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, long known for its promotion of organized hate. Its decree included championing racial segregation at every turn and called for fidelity in marriage. The reasons behind Ali's radical religious transformation are mostly steeped in conjecture and while the film's voices try to unpack it the best they could, it leave viewers to draw their own conclusions about his religious core.

The film dives deep into Ali’s frequent extramarital affairs, even detailing how his wife and entourage would arrange liaisons for him.

Ali learned early, contrary to popular belief by today’s hot-take crowd, that legacies were determined solely by the person, not by what others thought about his life.

His refusal to be drafted into the United States Army is a perfect illustration of this, as Ali put that legacy in jeopardy by saying, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong” and the 1971 Supreme Court decision that overturned his conviction allowing him to return to his craft after losing three and a half years in virtual boxing exile.

The 1974 "Rumble in the Jungle" fight against George Foreman is much of the focus of the third and fourth portions of the documentary, and accentuates the attention to detail in the filmmaking, along with the “Thrilla in Manila," his finale with Frazier, which many think should have never taken place or should have ended Ali’s career.

The last half-hour of the documentary focuses on Ali’s refusal to stop fighting, his generosity and philanthropy, subsequent struggle with Parkinson’s disease, its devastating effects and his enduring impact he has left on the world.

Near the end of his 74 years, we see a man who not only was admired as an activist, copied as an athlete and icon but deeply flawed as a human being, as we all are.

He regretted his treatment of Frazier and Malcolm X, but then would make sure strangers or anyone who asked had money. “Service to others is often the rent you pay for your room here on Earth," Ali once said.

This documentary, though not as expansive as other Ali profiles in terms of certain subject matter, more than gives Ali his rightful due. It highlights his grace and humility and ultimately reveals someone who deserved to be called “The Greatest" but further cements his place in history that few others have achieved..

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 'Muhammad Ali' documentary by Ken Burns doesn't overlook boxer's flaws