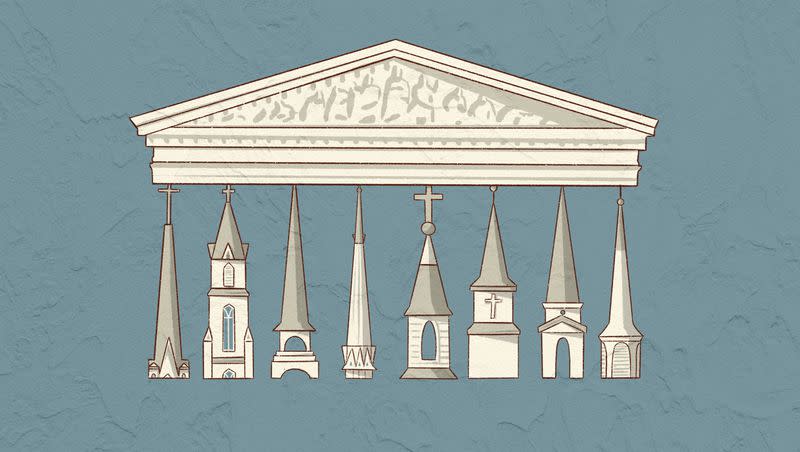

Opinion: How people of faith have shaped America’s Constitution

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s note: For years, the Deseret News’ editorial page carried the epigraph: “We stand for the Constitution of the United States as having been divinely inspired.” In honor of Constitution Month, the Deseret News is publishing a variety of articles examining the Constitution’s continued importance.

The liberty to speak freely on issues of consequence. The chance to vote for our representatives. The freedom to join others to promote causes we care about. The right of protection from invidious discrimination.

This month’s commemoration of the U.S. Constitution gives us a chance to reflect on privileges and freedoms — those listed above, plus many others — that are easy to take for granted. These freedoms were certainly not taken for granted prior to American independence, and they have not always been consistently extended to all Americans over the nation’s history.

That we have become used to them is the result of heroic efforts and sacrifices by statesmen and stateswomen, soldiers, and many uncommon “common” men and women. But there is another group of Americans whose contributions ought not to go without recognition: people of faith whose defense of their beliefs led to rights and established precedents that have benefited all Americans.

Of course, there would be no United States but for the pursuit of religious freedom, since that was such an important motivation for many of the original colonists in coming to this land. But that is just the beginning. Much of our nation’s progress securing essential liberties owes — at least in part — some credit to Americans of faith throughout its history.

People of faith were instrumental in abolishing slavery. While some Christians justified the practice of slavery, many others made remarkable efforts to secure its abolition. One academic historian noted: “The abolitionist movement was primarily religious in its origins, its leadership, its language and its methods of reaching the people.”

The remarkable Harriet Tubman was a person of great faith. She “led about a dozen rescue missions” to free slaves and, during the Civil War, “helped guide three Union steamboats around Confederate mines and then helped about 750 enslaved people escape with the federal troops.” Another historian explained: “Tubman’s Christian faith tied all of these remarkable achievements together,” saying her “belief in God helped Tubman remain fearless, even when she came face to face with many challenges.”

In 2020, the U.S. celebrated the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, which ensured all women the right to vote in federal elections. (Utah and Wyoming had extended that right in their territories half a century before.)

As with slavery, there were people of faith on both sides of the suffrage issue, but women of faith played important roles in the suffrage movement. Frances Willard of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union promoted a state-by-state strategy and “was successful in inspiring reluctant women to support suffrage.” Emmeline Wells, a leader in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was influential in securing the vote for women in Utah and became the vice president of the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1874.

People of faith have contributed to increased freedom not only by exercising their rights to promote causes informed by their faith, but also by seeking to secure their rights of free exercise in ways that established protections that now benefit others.

Related

For instance, in 1943, the Supreme Court issued a decision that established the crucial free speech principle that the government cannot force citizens to endorse a message with which they do not agree. The case involved two young girls who were expelled after they would not salute the American flag because of their family’s Jehovah’s Witness beliefs. The court’s opinion included an influential passage that has often been invoked: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

The protection from compelled speech has since been applied to protect a wide variety of nonreligious causes. A New Hampshire man objected to displaying a motto on his license plate; a Florida newspaper objected to publishing a mandated editorial; pregnancy resource centers objected to sharing a “government-drafted script ... to inform women how they can obtain state-subsidized abortions”; and public employees objected to endorsing the message of their union. All of these secular causes have, in part, the religious roots of free speech to thank for the rights they won in these cases.

Another example is the right of association. Derived from the First Amendment, this is a right of citizens to be free to join others to pursue a common cause. As noted above, the settling of the American colonies by religious dissenters was an early assertion of the right of association. The Establishment Clause, which prevents the creation of state-sponsored churches, also prevents the disruption of associational rights that could come from things like government direction of religious practices, direct tax funding of churches and clergy, or government interference with the operation of churches.

Here too, these assertions of religious claims for protection of the right to association — and others like the Boy Scouts’ successful effort to ensure it could ask volunteer leaders to affirm the message of its organization — have bolstered rights for others.

The NAACP, teachers who supported civil right and conservative nonprofit groups have all benefited, in part, from the religious roots of the right of association. This First Amendment right prevented the coercive disclosure of the names of members or supporters to government officials, which those groups or supporters reasonably feared would have resulted in backlash against the individuals named.

Protection of the rights of others is not a zero-sum game where some benefit only if others do not. These examples (and others) make clear that increasing the freedom of people of faith and religious organizations to exercise their convictions is not only the right thing to do, but it also increases the circumference of freedom for others.

William C. Duncan, J.D., is the Constitutional Law and Religious Freedom Fellow for Sutherland Institute, an independent nonpartisan public policy think tank in Salt Lake City.