OPINION: Black Exceptionalism and exclusion at Pine View

In 2019, then-presidential candidate Joe Biden urged the American people to recognize that “the next [Black] kid wearing a hoodie may very well be a poet laureate and not a gangbanger.”

While listening to Biden's speech during the summer after ninth grade, I was reminded that my imposed responsibilities as a Black teenager include demonstrating my value by showcasing a resume overflowing with academic accolades and talent.

At my school – Pine View – I felt the weight of this responsibility as one of four Black students in my grade of more than 200 people. I felt that if I did not meet that level of intellect and accomplishment, if I did not have A’s to exchange for empathy, I did not deserve a seat at the school or respect from its teachers.

I was in the sixth grade, my first year at Pine View, when my science teacher walked me out of class to tell me that Pine View was “not a place for every student” – and to also state that I “should strongly consider“ returning to my districted school. He remained my science teacher throughout middle school, and he continued to encourage me to look elsewhere, suggesting that the intensity of Pine View was beyond my ability.

Seven years later, I still find myself questioning my intelligence, wondering whether I’m suited for the rigor that awaits me in college – and if my professors will cast doubts on my intellectual capacity that resemble those that were frequently expressed by my science teacher.

After receiving acceptance letters to study applied science from Harvard, Princeton and Columbia earlier this year, I was transported back to my middle school experience – years that saw me form intimate relationships

with Saturday detention, the assistant principal’s office and report cards riddled with C’s.

I am devastated by the indifference of educators who wrote off my poor performances and disciplinary sanctions as evidence of low academic ability and behavioral issues. But I would be disappointed if the intent behind my words is misinterpreted: I feel no anger toward any of my middle school teachers and I acknowledge that, at times, I deserved their condemnation and dismissal.

The true purpose of this piece is to raise awareness about the factors these teachers failed to consider – or, more precisely, the questions they failed to ask – when shaping their perceptions of me as a student.

Did they ever, for example, ask themselves questions like:

What disparities in preparation are responsible for this student’s performance?

How can I support this student through their transition in a manner that’s empowering and not judgmental?

When a student openly appears to be uninterested, unprepared and unmotivated, it is a teacher’s obligation to question what traps lie between the student and potential success. But often teachers in gifted

programs adopt a Darwinian, ”survival of the fittest” perspective that leads them to believe that intelligence is reflected solely by academic excellence – and that the lack of such excellence indicates intellectual inferiority.

Unfortunately, this perspective – which reinforces the often-misguided presumption that all students have equal support systems and resources – has detrimental repercussions for low-income and minority students.

To achieve true socioeconomic and racial diversity, Pine View must be reimagined as a school that is more accessible, more inclusive and more supportive. Black students do not owe their teachers any form of “Black

exceptionalism” in order to be embraced or welcomed.

We are allowed to be works in progress. We are worthy of being treated with forgiveness, faith and compassion

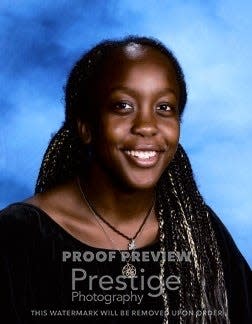

Victoria Kishoiyian is a graduating senior at Pine View School and will attend Harvard College this fall.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Pine View School must truly open its arms to all students