Opinion: Rev. King’s advice for developing compassion? Learn to see another’s point of view

Editor’s note: This story was originally published Jan 17, 2023.

“Here is the true meaning and value of compassion and nonviolence, when it helps us to see the enemy’s point of view, to hear his questions, to know his assessment of ourselves. For from his view we may indeed see the basic weaknesses of our own condition, and if we are mature, we may learn and grow and profit from the wisdom of the brothers who are called the opposition.” — The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

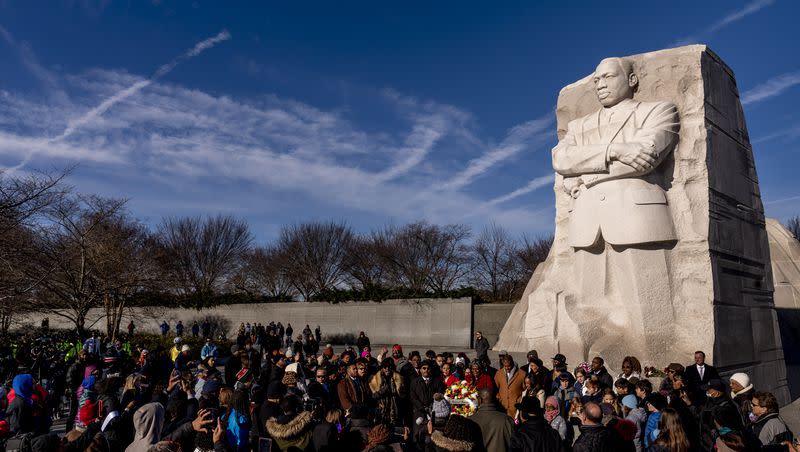

King spoke these words in the context of the Vietnam War, and yet they still apply today. Learning to see the humanity of others, to allow ourselves to be compassionate toward people who live different lives from our own, to honor others’ stories, are traits still urgently needed as we move along the path to fulfilling King’s dream, even after Martin Luther King Jr. Day has passed.

I am a white, educated woman, with a home that has clean water that comes from the tap anytime I turn it on, the ability to keep the indoor temperature at a comfortable level year-round, the ability to go to stores with an almost unlimited number of choices — even mangoes, strawberries and avocados in the dead of winter.

Unlike others, I’ve never lived in extreme poverty. I’ve never been unsheltered, suffered the effects of severe malnutrition or been followed in grocery stores because of the color of my skin. Without even knowing it, we can become stuck in a single story: our own.

I recognize that I am blessed. Privileged. I also know that many others have different lived experiences and that they are just as valid and real as mine.

When Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie tells her story in her popular TED talk, “The danger of a single story,” we get a glimpse that our experiences are not, in fact, universal. All the books Adichie read as a child described children who had blue eyes, blonde hair, played in the snow and ate apples — even though she lived in Nigeria, ate mangoes and had never seen snow.

Related

As a white mom of Black children, I’ve learned being ‘colorblind’ is problematic

‘Color-blind’ people won’t heal America’s racial divide. Try to be ‘color-blessed’ instead

Whose stories are we missing?

From the macro-level of state and nation to the micro-level of our own homes, we all have stories that are talked about, laughed or cried over and repeated again and again. But, we also all have stories that have been or are being erased, lost, forgotten. If there is such a thing as “collective remembering,” there is also “collective forgetting.”

Take the stories of the Chinese immigrants who helped build the Transcontinental Railroad. Do you know them? Were you taught those stories in school? How did they live? Why did they immigrate? Who did they love? What were they proud of? What losses did they grieve?

Or what about the amazing women of Utah whose stories are being told by Better Days 2020? Women like Mae Timbimboo Parry, who spent a lifetime collecting, preserving and sharing the stories of her Shoshone people, including the real story of the Bear River Massacre. Or Alice Kasai, who was born in the United States, married and living in the Avenues in Salt Lake with her husband Henry and their six children when Pearl Harbor was bombed. Henry was arrested and although he was never charged with a crime, he spent 21⁄2 years in an internment camp for Japanese people.

There are stories of Native Americans who were here to greet the Pilgrims. There are stories of slaves. There are stories of the Irish who came during the Great Potato Famine, and Armenians who fled a genocide and pioneers who crossed the plains in search of religious freedom — and slaves who crossed the plains at their owner’s demands. Stories of the Great Migration, when Black people left the South and spread across the country, sharing safe spaces through the “The Negro Motorist Green-Book.”

Their stories matter. So do yours.

When your stories are the ones quashed, forgotten or erased, it takes courage to tell them. It takes some vulnerability to believe that this time, those stories might just be heard. There are many good people working deliberately and proactively to invite people to come to the table and share their stories, people who, for far too long, have not had a seat at the table. Unfortunately, it too often seems that people who have lived lives of privilege dismiss, mock and deny the stories of those with less privilege. By stomping on those stories, by claiming that they are not true, or that the storytellers have an agenda, we’ve just told them their lived experiences don’t matter, that we don’t believe them and that we don’t really care after all.

Just because it hasn’t happened to you doesn’t mean it hasn’t happened. What if we asked ourselves how we could be better at empathy and understanding each other’s stories. What if we made space for their story to be true and our story to be true? What if we valued each other enough to say “Tell me your story” and then we truly listened with an open heart? I want to live in that world. I like to think King would have wanted that too.

Holly Richardson is the editor of Utah Policy.