Opinion: What it says about America when Jackie Robinson’s statue is destroyed

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s Note: Mark Dent is the co-author of “Kingdom Quarterback,” a book that tells the story of the historic struggles of Kansas City alongside the rise of Patrick Mahomes and the Kansas City Chiefs. He is also a senior features writer for The Hustle. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. Read more opinion at CNN.

Statues don’t just celebrate historical figures. They reveal truths about the people who commission them, showcasing the ideals they value most, or at least the ideals they want to convey. Sometimes they even trumpet the values that the broader society claims to espouse.

It’s not surprising then, that baseball legend Jackie Robinson has more statues in the US than any other baseball player, according to Christopher Stride, a professor at the University of Sheffield in the UK, who studies sports statues. Stride says there are at least 10 statues honoring Robinson across North America.

Robinson stands for the best of America: the hard-fought gains of the civil rights movement, undeniable athletic excellence and unwavering self-belief in the face of relentless racial oppression. Sadly, one of the statues meant to honor him became the focus of national headlines in recent weeks, for a most unfortunate reason.

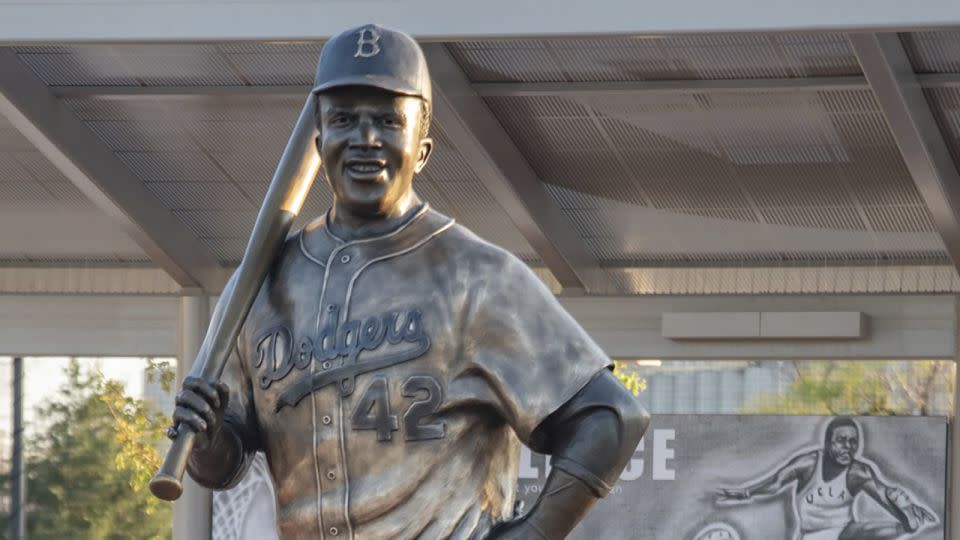

In 2013, Bob Lutz, a retired journalist from Wichita, Kansas founded a youth baseball club with the goal of making the sport more accessible to disadvantaged children. He named his baseball program “League 42” in honor of the number the Robinson wore on his uniform and hired a local sculptor to erect a statue of the baseball great at a local park.

How appropriate, it seemed, to grace the facility with a bronze likeness of one of the sport’s groundbreaking Black icons. “He’s kind of the ultimate symbol of what we want to represent and present,” Lutz told me.

But if erecting a statue of Robinson symbolized hope for a better America, what does it reveal about our country when a statue of Robinson is destroyed?

Last month, the statue in Wichita was wrenched off its pedestal and stolen. Days later, the fire department found pieces of the figure burning inside a trash can. The statue’s socks and shoes were all that remained at League 42’s baseball field.

This week, Wichita police announced the arrest of a 45-year-old man in connection with the crime. Police, who said there was no evidence of a hate crime, said they believe that the vandalism may have been motivated by financial gain: that the suspect intended to sell the bronze as scrap.

Regardless of what prompted the reprehensible act, it shocked a kids’ baseball league built to honor Robinson’s legacy, as well as many others throughout the Wichita community. And it was just one more indignity to the legacy of Robinson, who throughout his baseball career encountered countless slights and shameful abuse on the field and off.

The desecration of the statue serves as a reminder, especially during Black History Month, that many Americans must still work to understand and pass down the complexities of America’s sordid racial history, not to mention the complexities of Robinson.

Most Americans know a simplified version of the story of Jackie Robinson, who broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier on April 15, 1947. At a time when many institutions from public schools to the US military had yet to be desegregated, he brought America’s pastime — and the country itself — closer to its ideals of fairness and racial equity.

Since then, Robinson has been held up as a totem by some conservatives to indicate racism no longer exists. Some liberals like the author Robin DiAngelo have mischaracterized his story, robbing him of his agency and casting him as the beneficiary of a White establishment that finally permitted a Black man to play.

Robinson was an exceptionally talented and steadfastly determined four-sport athlete at UCLA. At the time of the draft, he was by no means the only Black player qualified to play in the Major Leagues. He was however, the player Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers deemed would be the most acceptable face of a controversial move to integrate America’s favorite — and until Robinson’s arrival, all White — pastime.

Robinson had no illusions about life in an integrated America, however. Born to a sharecropper father in Georgia, he was raised by a single mother in Pasadena, California, a community he considered more “openly hostile” than the South. “Pasadena regarded us as intruders,” he once wrote. “We saw movies from segregated balconies, swam in the municipal pool only on Tuesdays and were permitted in the YMCA only one night a week.”

Robinson’s signing by the Dodgers, which came after years of pressure from unions, civil rights activists and Black and socialist newspaper editors, counted as a major victory for the broader civil rights movement. He then exceeded the expectations of millions of hopeful Black Americans and spoiled the desires of millions of White Americans rooting for his failure — some of whom shouted racial slurs from the bleachers, sent hate mail and made threats against his family.

When his Hall of Fame career ended, Major League Baseball would’ve preferred Robinson to “stick to sports.” He did not. Robinson founded a bank in Harlem that helped Black residents secure loans for businesses and housing. He and his wife, Rachel, had been denied when they tried buying a home in the New York City suburbs, eventually settling in Stamford, Connecticut. He wrote syndicated political columns, criticized police brutality and stood up for the Black Panthers. “A sit-inner before the sit-ins, a freedom rider before the Freedom Rides,” Martin Luther King, Jr. once wrote in homage to Robinson.

But Robinson defied facile labels in his activism, facing criticism from Black leaders like Malcolm X for his support of the Republican Party. Then, after backing Richard Nixon in 1960, Robinson skewered the Republican establishment for nominating Barry Goldwater in 1964, saying the Party was in danger of “being taken over by the lily-white-ist conservatives.”

Robinson made his last public appearance at the October 1972 World Series. He threw out the ceremonial first pitch and lambasted Major League Baseball for its failure to hire Black managers. He died of a heart attack nine days later.

His autobiography, “I Never Had It Made,” came out that fall. “I cannot say I have it made,” he wrote in the epilogue, “while our country drives full speed ahead to deeper rifts between men and women of varying colors, speeds along a course towards more and more racism.”

Many Americans then, as now, did not accept that racism is embedded within the United States. And the recent push to make Americans more aware of the nuances of redlining, segregated pools and other historic racial injustices that give full context to the battles fought by Robinson — and their residual effects — has been met by resistance. Books on Black history and culture have been banned. Curriculums in high schools are being sanitized, with Black history being treated as if it’s separate from American history.

There’s also been physical damage to Black history symbols in the last year: signs for an African-American history trail vandalized in New Jersey, artwork depicting a historic Black neighborhood destroyed in Florida, a gravestone desecrated at a burial ground for the enslaved in Virginia.

And the vandalism in Wichita was not the first time a Robinson memorial was damaged. Vandals wrote the N-word and antisemitic comments on a Robinson statue in Brooklyn in 2013. Somebody shot at a Robinson historical marker in Cairo, Georgia, his place of birth, in 2021.

A year later, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, showcased the damaged sign in a dugout at the museum’s Field of Legends exhibit. (Robinson played one year in the Negro Leagues for the Kansas City Monarchs.)

Bob Kendrick, the museum’s president, once told me that he believed that damage to the marker symbolized the fact that more work is needed to combat racism. When he heard the Wichita statue was vandalized, Kendrick said he felt hurt to his core saying that the act, whatever the purported motivation, was hateful. “It does kind of serve to remind us that hate has indeed resurfaced in this country in ways that we don’t want to think that it has,” he told me. Kendrick worried that the vandalism against the Robinson statue may scar the Wichita community and the children who play baseball in League 42.

But here’s where Robinson, looking down from baseball heaven, may be having the last laugh, because the vandalism has in fact left an imprint. Paradoxically, it has helped to burnish Robinson’s legacy. The grievous misdeed of destroying Robinson’s statue has only increased the kids’ awareness of the illustrious details of his storied life and its relevance to their own, Kendrick says.

And Kendrick said his spirits also have been lifted by the public response to the crime. Nearly $200,000 in donations has poured in as of this week and Major League Baseball has also pledged to help fund a new statue.

The entire lamentable episode offers, in the end, a heartening reminder: When monuments to our historical heroes get attacked, people of good will try even harder to learn about that history and understand it. When tributes to our greatest legends get defiled, the public will redouble their efforts to lift those heroes up.

More often than not, people don’t just sit back and accept indecency and injustice. They fight back — just like Robinson did.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com