Opinion: Goodreads controversy goes far beyond a bad review

Editor’s Note: Kara Alaimo, PhD, an associate professor of communication at Fairleigh Dickinson University, writes about issues affecting women and social media. Her book “Over the Influence: Why Social Media Is Toxic for Women and Girls — And How We Can Take It Back” will be published by Alcove Press in 2024. The opinions expressed in this commentary are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

Goodreads, the social platform for reviewing books, is becoming a place where people are going to trash books they haven’t read. This trend isn’t new, but according to a recent article in the New York Times, it’s pervasive.

Six months before publication of Cecilia Rabess’ book “Everything’s Fine,” about a Black woman who falls in love with a White, conservative man, the book racked up tons of one-star reviews (though the overall split among ratings was mixed).

The same thing happened to Elizabeth Gilbert’s book “The Snow Forest,” which was slated to be published next year, after readers objected to the fact that her novel took place in mid-20th century Siberia because they disagree with the modern, real-life Russian government’s war in Ukraine.

Shockingly, Gilbert decided not to publish it. Other authors have also been on the receiving end of withering pre-publication critiques – before users could possibly have even read what they’d written.

Goodreads (which is now owned by Amazon) has got to stop allowing these kinds of abusive campaigns against authors. If the site keeps devolving into a place for unreliable reviews, people won’t trust it anymore – and readers will lose some of the power social media has given us to participate in public discourse about books, their cultural significance and their popularity. (In a statement to The New York Times, Goodreads said it “takes the responsibility of maintaining the authenticity and integrity of ratings and protecting our community of readers and authors very seriously,” adding that it’s taken steps to address content that violates the site’s guidelines.)

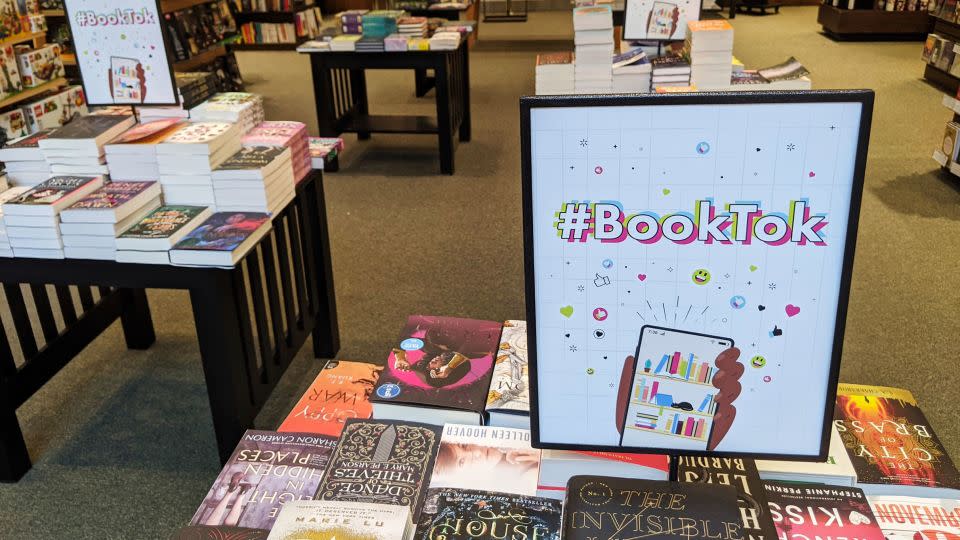

The beauty of platforms like Goodreads and BookTok – the devoted corner of TikTok where users post reviews – is the way they’ve democratized book readership. The publishing industry has always been heavily guarded by gatekeepers: the literary agents, book editors and reviewers who determine what books get into print and become popular. But today, thanks to readers (and social media), authors without those kinds of privileged literary-world connections or books that generate highbrow reviews can also break through.

Take Colleen Hoover. In January 2012, when she self-published her first novel, “Slammed,” she was living in a trailer with her husband and three children and earning $9 per hour at her job. Today, she’s regularly on The New York Times bestseller list – thanks to the fans, who call themselves CoHorts, who’ve championed her work online.

Reader reviews can also help make (or break) books published by mainstream publishers – and that’s important, because it gives the public some of the power to decide what becomes popular. When my book, “Over the Influence: Why Social Media is Toxic for Women and Girls – And How We Can Take it Back,” is published next year, I sure hope it’s taken up by major book reviewers and the kinds of book clubs who can turn it into an instant bestseller. But I can also imagine that regular readers might connect more with the book than celebrity reviewers.

For example, people like Oprah probably aren’t on Tinder for many reasons – not just because they have partners. (I’m sure being a celebrity comes with an added layer of dating challenges.) But that means my readers might connect with the way I write about the horrors of online dating in a way that some powerful gatekeepers might not. And most reviewers probably aren’t old enough to have dealt with problems like “sharenting” (when parents post about their kids on social media) as they grew up – but the part of my book about teens and social media might speak powerfully to my younger readers. So, reviews by readers will be important to my book’s success.

That’s why, when I read, I often pick books because they’re recommended by people with similar tastes to me, such as Reese Witherspoon or Jenna Bush Hager – but I also read ones recommended by my friends.

Goodreads and other discussions of books on social media can also get people reading more. That’s especially important for young people who have come to spend so much time on social media.

One study found that, in the late 1970s, 60% of high school seniors read a book or magazine every day. By 2016, only 16% did. Of course, plenty of young people read articles on social media and other platforms, but reading a physical book allows you to disconnect from the world and think about one thing in ways that reading an article online – with notifications possibly constantly popping up on your screen – just doesn’t.

Since reader reviews are so important, Goodreads needs to get its site together and stop allowing mobs of non-readers to censor authors, so we can trust the reviews we read.

To state the obvious, the platform shouldn’t allow reviews to be posted before a book is published, when lots of people couldn’t possibly have read it. It could also use algorithms to detect bots and reject fake reviews (researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have shown how this is possible, since bots often use less unique words than humans and are connected to other bots, for example). It should give more weight to reviews by people who write more reviews over time (rather than potentially being biased against a single book) and who aren’t serial book-trashers.

Goodreads reviews are quickly becoming unreliable, but it’s not too late to fix the problems with this site. Sure, that would be a happy ending for authors – but it would be all the more so for readers, because it would ensure we keep some of the power to determine which books break out.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com