Opinion: 'Swine Republic' proves Iowa's water is contaminated. Can it help force change?

As I write this, "The Swine Republic: Struggles With the Truth About Agriculture and Water Quality" is temporarily out of stock on Amazon. According to Steve Semken, publisher at Ice Cube Press, demand is high, and the book is now in its third printing since it was released May 19.

Why’s a book about Iowa’s contaminated water so popular?

It's popular because Iowa’s water is contaminated. Its Corn Belt pollutants, a cocktail of fertilizer and manure, nitrogen and phosphorus, travel from Iowa's rivers and streams to the Mississippi River and then to the Gulf of Mexico, some 1,500 miles downstream. There, it causes algae to flourish, which then consume the oxygen needed for marine life. Plus, according to "Swine Republic" author Chris Jones, nitrogen also impairs our drinking water, causing "blue baby syndrome" in infants while being carcinogenic for adults.

It's popular because Jones, who has a Ph.D. in analytical chemistry, has been writing about and speaking about and educating Iowans (and beyond) about this problem on his now-defunct University of Iowa blog since 2016.

It's popular because Jones, who retired in May from UI's Institute of Hydraulic Research, where he shared his water quality research to his 200,000 blog readers, is still writing about and speaking about and educating Iowans (and beyond) about the problem.

More: University of Iowa researcher alleges blog posts drew funding threats from lawmakers

Jones is educating readers who want to read his latest musings at his new @RiverRaccoon Substack column. He’s educating the overflowing crowds filling most of his book events around Iowa. And of course, he hopes to educate readers of "The Swine Republic."

“I thought the public should know what the truth is,” Jones said, in answer to my question regarding the impetus for writing the book. “And because the issue is so politicized and so sensitive for a lot of people, I don’t think the truth of the matter is discussed very often.”

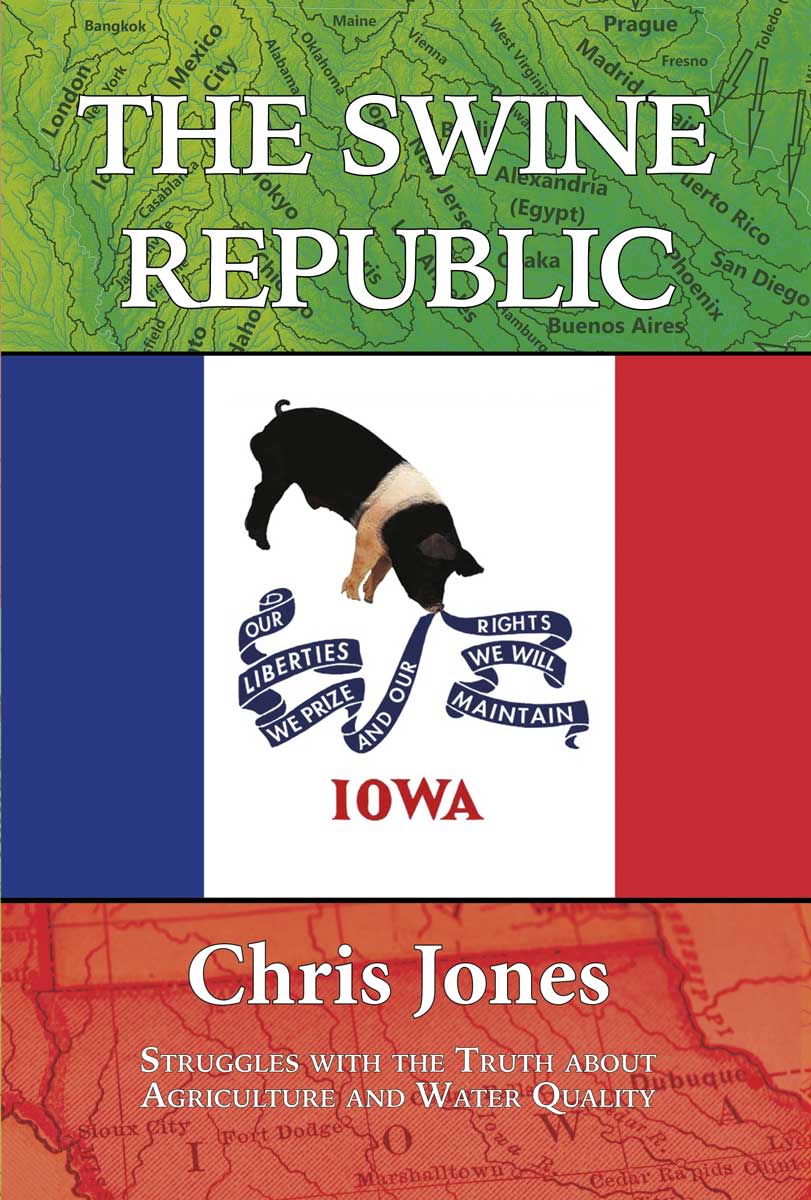

Why did Chris Jones title his book 'Swine Republic'?

"The Swine Republic" is a collection of Jones' water quality essays that appeared on his UI blog, each prefaced with updated information. It also includes a few new essays.

What an appropriate title for a book about a state that is the No. 1 hog-producing state at 23.4 million hogs, according to the USDA. This is more than 33% of the nation’s hogs, despite Iowa making up only 1.5% of the U.S. land, according to Jones.

What an appropriate title for a book that has chapters devoted to swine, such as Jones’ most-read blog post, "Iowa’s Real Population." This chapter reported that, while Iowa has a little over 3 million people, hogs excrete "3 times as much nitrogen, 5 times as much phosphorus, and 3.5 times as much solid matter,” which is equivalent to excretions of 83.7 million people. Add in beef and dairy cattle, then chickens and turkeys, and it's up to the equivalent of 134 million people, which would make Iowa the “10th most populous country in the world.” The visual of the map of Iowa filled with dozens of cities with populations that match the waste population is staggering.

In "Fifty Shades of Brown," Jones realized he'd underestimated the amount of “fecal waste” and, using updated USDA figures, calculated that “in Iowa we are generating as much fecal waste in every square mile as 2,979 people,” making us the No. 1 state.

What’s poop got to do with Iowa's water quality problems?

The poop pollutants make their way into our water.

In "MMPs Are Crap," Jones explains how manure management plans, or MMPs, don’t protect water quality. Using an example of a 10,000-hog farm where “manure is stored in an 800,000-gallon pit beneath the confinement which is emptied once per year and applied to a 200-acre corn field,” Jones calculates that this manure applied or injected into the field results in the addition of 53,655 pounds of nitrogen. This amounts to 268 pounds/acre. Since this is from 1.4 times to double the rate recommended by Iowa State University, depending on the crop, it results in over-application of nutrient, which Iowa “laws” allow via flawed MMPs. This excess then ends up in our streams.

More by Rachelle: OPINION: Homosexuality in Uganda is now punishable by death. LGBTQ+ Ugandans need help

MMPs aren’t the only management solutions that aren’t working. In the "Swine and the Swill," Jones discusses how Washington County, “the undisputed soil health and cover crop champion” — two things that are supposed to improve water quality — had E. coli and microcystin (a toxin produced by blue-green algae) warnings for Lake Darling. Crooked Creek was “one of the highest nitrate streams” in Iowa.

Is it a coincidence that, in 2017, Washington County produced the most hogs — about 1.3 million — in Iowa?

It's the nitrogen and phosphorus in poop and fertilizer that's the problem

The pathway of nitrates — from commercial fertilizer as well as manure — from the soil to the stream is helped via tile drainage. In "Cry Me a Raccoon River," Jones points out that the Raccoon River supplies water for the Des Moines metropolitan area and that, since 1992, Des Moines is the largest city in the U.S. (and perhaps the world) that removes nitrate from its source water “to comply with safe drinking water regulations.” The chapter includes a photo of spools of drainage tiles in the North Raccoon watershed, waiting to be unspooled and put in the ground.

“There's 2 million miles of that stuff (tile) in Iowa,” Jones told me. “Farmers put that 4 feet down in the fields to lower the water table and that optimizes conditions for corn, soybean production because our soils retain water.” But Jones stated that the tile is also the primary delivery mechanism for nitrates. "So when we put tile in the ground, it increases the flow of nitrate from the fields to the streams.”

Thus, tiling makes the problem worse.

Then, climate change compounds the problem. “Not so much with increased temperature,” Jones said, “but with increased precipitation. So when it gets wetter, farmers then become inspired to put more of that tile in the ground, and then that causes the nitrate problem to be worse.”

In May, Jones wrote a guest column for the Register about the importance of water quality sensors that monitor and collect data from 60 streams throughout Iowa, and how Republican-led legislation (though Jones stresses that Iowa's water quality problems are bipartisan) sought to reduce funding. In "Iowa is Hemorrhaging Nitrogen," data-lovers can geek out on the plethora of sensor data and calculations and charts that show just how bad the nitrate stream load was in 2019, i.e., 980 million pounds.

More: Opinion: Suppression of Iowa water quality data is an attempt to control you

But nitrogen isn’t the only contaminant. Phosphorus is another.

In "Don’t Pee Down My Leg and Tell Me It’s Raining," Jones discusses the 11-year-old Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy and its focus on practices farmers can adopt to reduce the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus flowing in streams by 45%. Jones’ major issue with this strategy is the reporting of the progress or success without data. Both in person and in his book, he said data from water sources shows that, in the last 20 years, phosphorus levels are increasing.

“But the industry is looking at this practice adoption,” Jones said. "Well, the thing with the practice adoption, you're just looking at one side of the ledger. You're not looking at the things that you're doing that are bad, that are increasing — like the number of hogs.” Jones said that the number of hogs in Iowa has doubled over the last 20 years, and that little nugget gets omitted in the practice adoption model. “That's one of the main points of that particular essay,” Jones added. “Don't tell me it's improving when you know it's not.”

More: Is Iowa's water cleaner after ten years of state efforts? It depends who you ask.

This is just a sampling of the issues and points and data — lots and lots of data — included and discussed in "The Swine Republic" and its 68-plus chapters.

Jones endeavors to end things on a positive note

In the final chapter, "Downstream," Jones offers solutions. He starts the chapter by saying people often ask him what can be done, which is what I had been wondering, too. Fortunately, he didn’t just say, “Vote,” the often-touted solution for all things. Sure, voting is important. But it doesn’t feel like one’s doing anything to help on an individual level.

“That was very well stated,” Jones said when I’d told him that. “You're not doing anything as a person other than dragging your body to the voting booth. Yeah, it's got to be more than that, for sure. We have a huge, intractable problem here that's decades long, generations long. And, you know, it's only going to change if people demand that change. And voting is not enough.”

Jones groups the solutions to water quality problems into three areas (no spoilers here — you’ll have to read the book for the ending). But any and all solutions are going to take all of us to change things.

“If people want to effect change, then it's got to be done at the grassroots level,” he told me. “They have to agitate for water quality with their local elected people — county supervisors, city council, and so forth. I do not think change is gonna come from above.”

Jones wants his book to inspire “some of that grassroots sort of enthusiasm” to effect change.

“Sometimes it can seem hopeless, but the future is just an endless series of precedents,” Jones said. “So we just have to act in the present as best we can and hope that this is manifested in change at some point. And so that's what I'm trying to inspire."

Rachelle Chase is an author and an opinion columnist, who's also launched a new column, Trailblazers & Trendsetters, at the Des Moines Register. Follow Rachelle at facebook.com/rachelle.chase.author or email her at rchase@registermedia.com.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Opinion: Will 'Swine Republic' readers demand Iowa clean up its water?