Opinion: Top 10 Des Moines City Council financial disasters since 2000

David Letterman famously developed the “Top Ten” list format to skewer a topic of the day for his late-night television audience. It became a widely mimicked bit and a permanent fixture in the turn of the century culture from college graduations to Rotary clubs.

I wish the one I am offering was remotely funny.

For the past 20 years, the Des Moines metropolitan area has grown and prospered. But while the suburbs pushed the metro area to a 16.3% population increase in the past 10 years (the fastest-growing area in the Midwest), the City of Des Moines lost population by 1%.

Rankings and awards seem to come easily, but when we peel back the veil of our political leadership, we find disturbing results. When any growth strategy is analyzed, the question must be: Were the outcomes worth the cost? For Des Moines, the answer is just not funny. The ambivalence and lack of due diligence on the part of elected leaders of Des Moines generated mistakes and debacles, and revealed outright incompetence at a level not previously seen in the city.

Of course, not all present council members have been in office throughout the period (except for the mayor, who has been here for all of it, but he alone cannot be blamed for this list). I ran against the mayor in 2019.

And now, here is a list of the 10 most costly mistakes the Des Moines City Council has made since 2000:

10. Forfeiting the most valuable land in the city to the federal courthouse and giving up millions of dollars in future property taxes. The old YMCA site on the Des Moines River was unceremoniously forfeited to the federal court system after the city couldn’t convince the chief judge to choose another site and allow a local developer to build an apartment complex. As a result, the city lost approximately $2 million annually in property tax revenue to an entity that pays no taxes. So, instead of a private, taxpaying, commercial and residential building, the highest valued land in the city goes to the federal government.

9. Handing millions of dollars of financial incentives to Wells Fargo. In 2000, the Des Moines City Council approved a $15 million grant to help the bank build a new office structure at 800 Walnut St. The bank also built a parking garage as part of the deal. Wells Fargo is due another $750,000 from Des Moines as part of the development agreement for 800 Walnut St. The city owes another $2.9 million as part of a separate agreement for 801 Walnut St. Unfortunately, the company’s commitment to downtown hasn’t lasted as long as the tax breaks did.

8. Selling 42 acres of prime development land in the East Village to the mayor’s cousin without competitive bidding, two weeks after the Mayor squeaked by in a run-off election in 2019.

7. Removing $2 million from the property tax rolls by purchasing the 360,000-square-foot corporate headquarters of Nationwide Insurance at 1200 Locust St. for the assessed value of $30 million for a potential new police headquarters. In addition, the city included the purchase of the Nationwide parking ramp at 1200 Mulberry St. for an additional $10.6 million. As a bonus to Nationwide when it was built, the city paid for construction of three skywalks for $2.3 million and gave Nationwide $1.2 million in tax abatement. And if that isn’t enough, the city negotiated giving Nationwide $7 million is grants over 20 years. Quite a deal for one of the world’s largest and most profitable insurance companies.

6. Deferring maintenance and security concerns in the 4.2-mile Des Moines skywalk system. This creates a deteriorating and unsafe infrastructure out of a Des Moines landmark. Once proclaimed as the “sidewalk in the sky”, the system made downtown a viable employer attraction and an employee-friendly place to walk from building to building without battling the cold winters and scorching summers. It also had something the suburbs didn’t have: art and cultural activities. The skywalk was supposed to provide a place to see and hear the creative side of a community. With sections closed and repair needs ignored, the skywalk neighborhood is becoming an eyesore and unsafe. And no one group is in charge, creating confusion and adding to the decay.

5. Ignoring the council’s responsibility to ensure the proposed regionalization of the Des Moines Water Works. While the DMWW is a separate legal entity organized by the Legislature, the mayor appoints all six members of its board of trustees. For five years, the trustees have been discussing reorganizing into a regional authority. That is a good idea — but what’s troubling is the City Council and mayor have left this major reorganization to six non-elected trustees with no accountability to the citizens of Des Moines. As of today, there is a proposal to regionalize but no record of the city council having a public discussion.

4. Somehow losing Des Moines University to West Des Moines along with 1,600 medical students who previously lived, worked and played in the city. The council ignored the school’s growth potential, offered no legitimate incentives, and left DMU no choice but to leave its Grand Avenue campus. The college has been involved in a months-long dispute with “South of Grand” neighbors over efforts to add a parking lot. An agreement with the city dating back to 2000 restricts development on the property. The retail, residential and commercial impact of this loss will be felt for decades.

3. Being sued by Des Moines citizens for illegally charging a franchise fee for cable TV installment and being forced to return more than $31 million to Des Moines residents the city illegally took. Former State Treasurer Michael Fitzgerald said in 2017 that his office was asked to help find the over 50,000 people who have unpaid claims. He said Des Moines had to repay around $31 million in franchise fees; about a third was yet to be claimed then. Fitzgerald started the Great Iowa Treasure Hunt in 1983 to return unclaimed property to Iowans.

2. Agreeing to a $133 million, 33-story multi-use apartment and commercial building that was never built, by a developer who went bankrupt. The developer promised to build on the old Younkers site on Walnut but traded that site for the vacant Kaleidoscope building. It's been seven years since Des Moines-based developer announced it would build a high-rise residential tower in downtown Des Moines; six years since it requested a change in height by seven stories to 33 after splitting with an investor who wanted it scaled back; five years since it transferred to another site, four years since it was scheduled to start; and three years since termination of a development agreement under which the city would have provided financial help to build the project. Now, another developer cannot secure financing after the city agreed to millions of dollars in tax incentives, but the development is not happening. Confused? So is the council.

More: Des Moines City Council to vote on Kaleidoscope demolition to clear way for new apartment tower

And the No. 1 catastrophic decision the Des Moines City Council has made in the past two decades is:

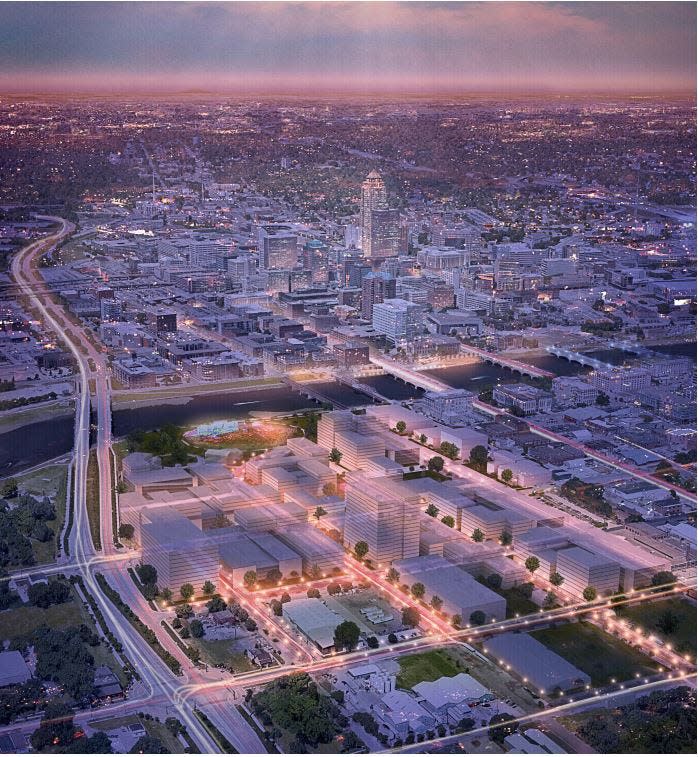

1. The $170 million, 40-story downtown condo building that has never been built. So far it has cost the city $42 million for a parking garage that will never be filled at a prime location in the Court Avenue entertainment district. Why? The developer and city are suing each other for $100 million, each blaming the other for reneging on promises and planned payments. With the goal of replacing an aging parking garage and taking advantage of a prime site in downtown Des Moines, the city began working with the developer to create a landmark project in exchange for millions in taxpayer funding. After all this negotiating, all we have is a parking garage and an artist’s rendering of the 40-story condo.

These disasters not only cost the residents of Des Moines over a hundred millions dollars of tax revenue that went down the drain, but will forever prevent more worthy projects from being proposed, better developers from taking action, and stronger investors from investing in the city, not to mention the loss of more activities our citizens would be able to enjoy.

We have an election for City Council and mayor coming up in November. We need to choose our candidates wisely and ask questions about our city’s future.

Jack Hatch of Des Moines is a former state senator. He was Democratic nominee for governor in 2014 and lost a runoff election for Des Moines mayor in 2019.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Opinion: Des Moines City Council top 10 financial disasters since 2000