Opinion: This unpalatable reality about antisemitism at Harvard

Editor’s Note: Lev Golinkin writes on refugee and immigrant identity, as well as Ukraine, Russia and the far right. He is the author of the memoir “A Backpack, a Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

Harvard University recently issued the latest in an ongoing string of attempts to underscore its commitment to combatting antisemitism, which has grown more evident in the wake of the Israel-Hamas war. The scandal over the school’s failure to address antisemitism on campus began this October, when a group of student organizations released a letter blaming Hamas’ massacres of Jews on Israel (a letter from which several signatory groups later retracted their support).

At first, the backlash was focused on the students; following a controversial public congressional hearing, the furor has swelled into calls for Harvard’s president Claudine Gay to resign. In an interview with the university’s student newspaper following her testimony, Gay apologized; “I am sorry,” she told the Harvard Crimson. “Words matter.” Harvard’s board has released a statement affirming their support for Gay.

But these calls for punishment and resignation overlook a critical point about history. In order to hold itself institutionally accountable for fighting antisemitism, Harvard must examine dark decisions made long before the students who had signed the Israel-Hamas letter were born — indeed, long before Gay herself graduated college. Certainly, Harvard has much to grapple with. This is an institution that once had explicitly antisemitic admissions policies, and one that still gives preference to legacy applicants — which some argue ensures the persistence of inequality.

A less known but deeply unpalatable reality when it comes to antisemitism at Harvard is that one of the top universities in America is an institution that honors a man convicted of crimes against humanity in Nuremberg; whitewashes a Nazi collaborator who organized the ethnic cleansing of tens of thousands of Jews and Poles; and celebrates an alumnus infamous for freeing Holocaust perpetrators and orchestrating the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

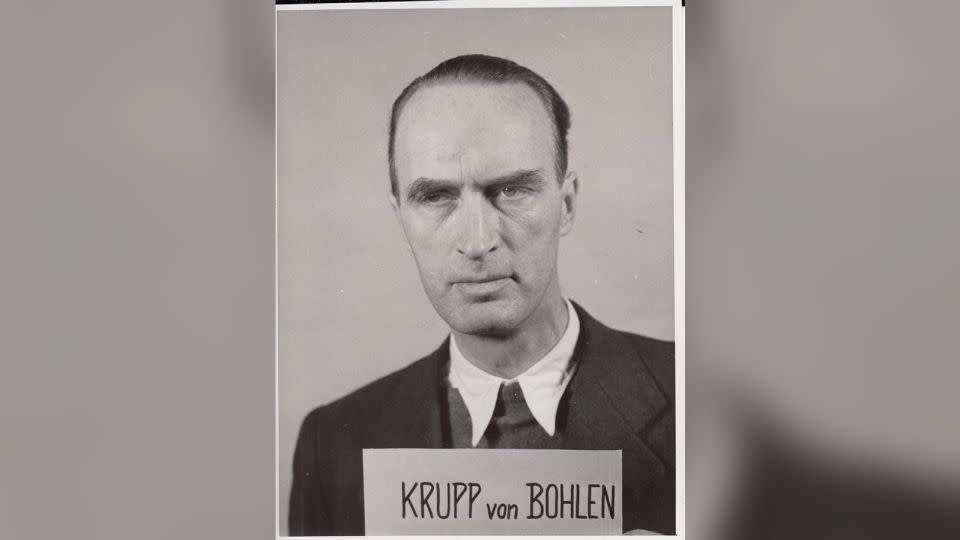

During the war, industrialist Alfried Krupp had an estimated 100,000 enslaved people working at his factory in Auschwitz. Today, a fellowship and a chair at Harvard bear his name. His foundation gave Harvard money. Harvard helps whitewash his legacy.

The concentration camp inmates, prisoners of war and hundreds of children who were enslaved under Krupp were subjected to abhorrent conditions and abuses. A Nuremberg prosecutor summed up the savagery by saying “When they could no longer work, the SS took them away to be gassed.”

After the war, the US held a set of 12 trials for war crimes committed by concentration camp doctors, death squad commandos and other facets of the Third Reich genocide apparatus. Krupp’s steel empire, which formed the cornerstone of Germany’s war industry, played a role so extensive that one of the 12 trials was devoted to it alone.

But Krupp only spent a few years in prison before his sentence was commuted by US High Commissioner for Germany John J. McCloy, a Harvard Law graduate who freed over two dozen convicted Nazis, including men directly involved in perpetrating the Holocaust.

McCloy’s shameful history doesn’t end there. The man played a pivotal role in blocking America from bombing Auschwitz, which many historians and observers (including Deborah Lipstadt, current US Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism, and Israel’s Yad Vashem) argue was a damning failure to act by the Allies. He also championed Japanese American internment; according to Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Kai Bird in his book “The Chairman,” McCloy was responsible “more than any other official” in convincing President Franklin Roosevelt to greenlight the internment.

Harvard’s profile of McCloy, which celebrates him as “very active and successful in a variety of fields,” mentions none of this.

Thanks to McCloy, Krupp was returned the assets that had been seized from him. Upon his death in 1967, the Nazi industrialist left that fortune to a foundation bearing his name; in 1974, that foundation gave $2 million to Harvard, which created the Krupp Foundation Dissertation Research Fellowship and the Krupp Foundation Professor of European Studies. (The Krupp fellowships are also awarded to students at multiple other universities, including MIT, whose president also currently faces calls for resignation due to her congressional testimony about antisemitism on campus.)

In marked contrast to October’s student letter, which sought to justify Hamas’ massacres, the sole documented protest I’ve found to Harvard accepting Krupp’s money in 1974 came from the Harvard Crimson. Harvard’s sites for the Krupp fellowships and the Krupp professorship fail to disclose that their honoree was a convicted war criminal or that the money came from arming Nazi Germany and participating in genocide.

Indeed, in a bit of grim irony, the mother of Gay’s predecessor, Lawrence Bacow — who was Harvard’s president until this July — was an inmate at Auschwitz. In an impressive feat of separating business and personal, Harvard celebrated the son of a Holocaust survivor becoming president while continuing to use funds gained from slave labor at the very same concentration camp where Bacow’s mother was imprisoned.

And Krupp isn’t the only Third Reich war criminal whitewashed by Harvard. The school’s Ukrainian Research Institute (HURI) features the archives of Mykola Lebed, described as “an important figure for Ukrainian history,” and a leader in WWII-era Ukrainian organizations that “were engaged at various times in struggles against occupying forces.”

HURI’s biography of Lebed goes on to portray him as an immigrant who became a scholar of the Soviet Union. A professorial photo of Lebed smoking a pipe accompanies the description.

Missing is the fact that the supposed freedom-fighter-turned-scholar was a Nazi collaborator and mass murderer trained by the German secret police the Gestapo, and later protected from prosecution by the CIA.

Lebed was a leader in the antisemitic and fascist Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), which allied itself with the Nazis and whose men participated in liquidating Jews. In 1943, Lebed became one of the commanders of an OUN paramilitary offshoot, where he was responsible for orchestrating the slaughter of 70,000 to 100,000 Poles in what’s called the Volyn massacres.

When it comes to sheer barbarity, photographs of what Lebed’s forces did to Polish villagers, including children, give Hamas’ most gruesome acts a run for their money. Even US Army Intelligence, which isn’t known for squeamishness, stressed Lebed was a “well-known sadist.”

The transformation of a butcher of Jews and Poles into the placid pipe-smoking professor on HURI’s site is telling, considering it’s done by an institution whose motto is the Latin word for “Truth.”

Indeed, in 2011, HURI’s Mykola Lebed Archive Research Fellow was Volodymyr Viatrovych who, shortly after leaving Harvard, became director of Ukraine’s Institute of National Memory — a governmental body that sets the country’s policy on interpreting historical narratives.

While there, Viatrovych became notorious for whitewashing Nazi collaborators, including Lebed’s organizations. This included drafting laws that made it illegal to deny their status as freedom fighters. Ukraine’s celebration of these collaborators was repeatedly condemned by the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and Israel.

If Harvard is serious about working to eradicate antisemitism on campus, it can start by ridding itself of its Nazi stains, not just for Jews but for the nearly 700 Harvard students killed fighting against the Third Reich. Otherwise, the notion of combatting antisemitism at a university that offers scholarships tainted by Nazi money will be little more than an obscene farce.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com