Opinion: So you want to become a better writer? Be a better reader.

People who write habitually – for work or for fun, journal entries or blog posts, book reports or short stories – often want to put their better foot forward, but the eccentricities and minutiae of the English language can be extraordinarily daunting.

As a professional word person, I know this as well as anyone: There’s always so freaking much to remember, from the basic differentiation between treacherous homophones (their, they’re, there), to the fine points of grammar (subject-verb agreement! the dreaded subjunctive!), to where to put the punctuation. (Some days I’m tempted to save up all the commas, colons and periods and dump them at the end of whatever I’m writing and leave it to the reader to sort out.)

These things are important, to be sure: God is in the details, they tell us, but so, they tell us, is the devil. And sometimes I’m simply asked for simple big-ticket advice on improving one’s writing.

QUESTION: If you had one piece of advice on how to be a better writer, what would it be?

ANSWER: I think that the best way to become a better writer is to become a better reader. We so often find ourselves skimming our way to comprehension, speed-reading through whatever’s in front of us in an attempt to glean the basic ideas – but often at the expense of appreciating the effort that went into the writing, and the beauties of nuance.

So I’d like to offer up, for your experimentation, an exercise I’ve attempted a few times in the past and have always found enlightening and rewarding.

Pick some relatively brief piece of writing you know you like – the first time I played this game I used “The Renegade,” a short story by my favorite writer, Shirley Jackson (whom you may recognize as the author of “The Lottery” and "The Haunting of Hill House") – and copy it out verbatim, either with pen or pencil on paper or, as I did (in part because my handwriting is so awful I can never read what I’ve written), keyboarding the words into a Word file.

Does your work email have emojis in it? 🤔 You're better off just getting to the point.

Because you can’t simply speed your way through this process, you may well, I hope, find that in the painstaking recreation of another writer’s writing, you may feel things and learn things you might never have otherwise felt or learned. You’ll note decisions about word choice, and how the writer uses certain words over and over again but offers up some words, for great effect, only once. You’ll take particular note of the uses of punctuation: densely in some places, sparingly in others. (Unless you’re reading Henry James, in which case it’ll be densely from here till sun-up.) You’ll hear in your head the writer’s use of, say, alliteration, or the way one character’s dialogue is differentiated from another’s so that you can tell them apart even without the writer telling you (as writers often helpfully do) who’s speaking.

You may well find, as I’ve found, that what’s going on in the writing will make its way up your fingertips and past your elbows and shoulders into your brain and you’ll gain key insights into what the writer was thinking in the initial act of creation. (I don’t mean to sound like a medium conducting a séance, but, truly, this can happen.) At the very least, I hope, you’ll gain key insights into the act of writing – as a physical activity, as a craft – independent of the often vexing and noisy self-consciousness of coming up with and writing down one’s own words.

What can we do?: A co-worker is always 'correcting' our grammar and spelling, making it wrong.

There’s a twin activity to be attempted here, to be sure. Take that brief piece of writing you know you like and read it aloud: to yourself, if you’re alone; to a little audience, if you’ve got one handy. We’re told that in the drizzly Swiss summer of 1816, lacking anything better to do and bereft of good Wi-Fi, Lord Byron, Percy Shelley, Percy’s girlfriend and eventual wife Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, and one John Polidori sat around reading ghost stories to one another, and from that came the challenge for the little group to write fresh stories of their own, and from that came Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking science fiction novel "Frankenstein." You may not find yourself writing a classic – or, hey, you may! – but at the least you can reconnect to the great pleasure of telling stories, and hearing them.

Which is how many of us got into this whole reading and writing business in the first place. Thanks, Mom!

My mom would have been 92: I struggle with what to call every first occasion without her.

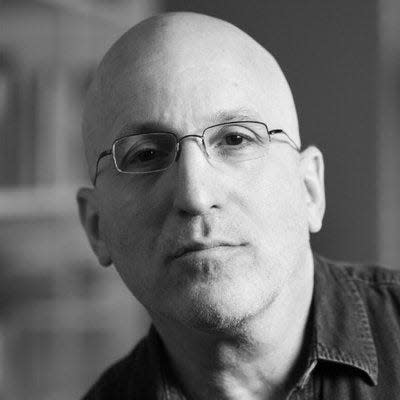

Benjamin Dreyer is the managing editor and copy chief of the Random House division of Penguin Random House and author of the bestselling "Dreyer's English." Do you have writing or grammar questions for him? Tweet him at @bcdreyer. Responses may show up in a future column.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How can you become a better writer? Start by reading.