Opinion: Where the brilliance of ‘Wonka’ truly lies

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s Note: Holly Thomas is a writer and editor based in London. She is morning editor at Katie Couric Media. She tweets @HolstaT. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author. View more opinion on CNN.

If Marvel has been Hollywood’s bread and butter for the last 15 years, then movie remakes have been its fries and ketchup. They’re rarely dazzling, but we find them almost impossible to pass up if they’re on the menu. In “Wonka,” directed by Paul King (see also: “Paddington” and “Paddington 2”), we find an offering that manages to fuse succoring nostalgia with delicious ingenuity.

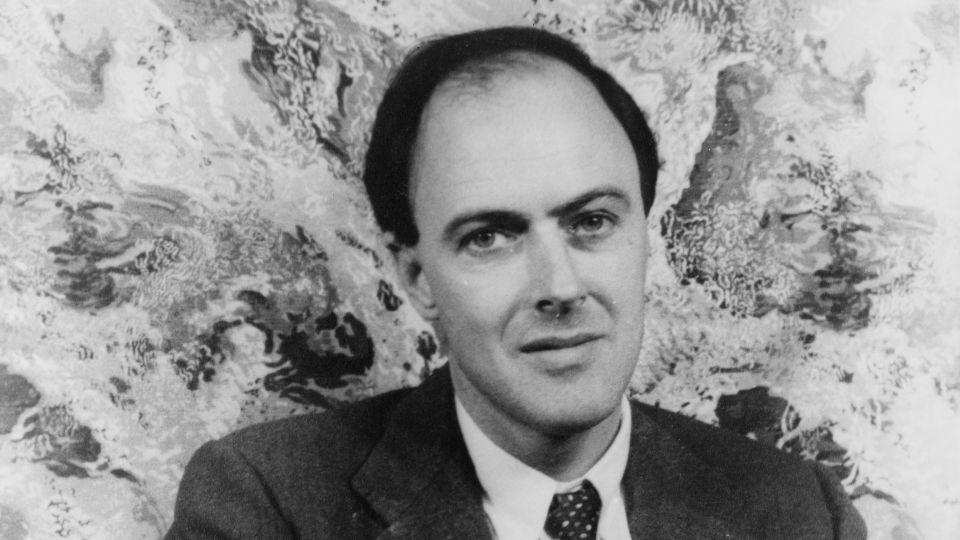

Some essential (spoiler-free) background: Unlike the 1971 movie starring Gene Wilder and Tim Burton’s “unhinged” 2005 effort starring Johnny Depp, “Wonka” isn’t based on Roald Dahl’s 1964 book “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.” Nominally, it’s a prequel, but the Willy Wonka so beautifully brought to life by Timothée Chalamet bears little resemblance to the inventor we’ve met before.

Instead of a creepy recluse inviting children to his factory for a covert series of Hunger Games-esque trials, this Wonka is a naive, pixie-ish youth. He lives out of a suitcase, is determined to solve strangers’ problems and makes his chocolate himself, rather than relying (as he does in the original text) on an anonymous army of Oompa Loompas trafficked to his factory and “paid” in beans.

There are fun little nods to Wilder’s version (a backward skip up steps, a quippy “strike that, reverse it”), and sweet tributes to Dahl (a very lovely giraffe). But in one neat move, “Wonka” has realized the secret to the perfect 21st-century adaptation, and saved its creators all manner of hassle. That is: Cherry-pick the best elements of the old story, then write a new one almost entirely from scratch. (The distributor of “Wonka” and CNN share a parent company, Warner Bros. Discovery.)

Over the last decade-plus, we’ve been served an almost ceaseless array of rehashed classics. Some have been triumphs (Greta Gerwig’s 2019 “Little Women,” Bradley Cooper’s 2018 “A Star is Born,” Jon Favreau’s 2016 “The Jungle Book”), and many — critically, if not always commercially — have fallen flat (Guy Ritchie’s 2019 “Aladdin,” Ridley Scott’s 2010 “Robin Hood,” Tim Burton’s 2019 “Dumbo”).

Sometimes, the magic sauce that separates the former from the latter is direction. “Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio” was released within weeks of Robert Zemeckis’ “Pinocchio” last year, but while Zemeckis spun a clunky melange of CGI and live-action, del Toro’s painstakingly constructed stop-motion musical imbued the fairy tale with subtle adult depth. Another sticking point is time. No one’s expecting 21st-century values in say, 19th-century Massachusetts — though you’ll get extra points if, like Gerwig, you manage to sprinkle some in convincingly. But when the original story isn’t definitively anchored in a specific era, you start to run into issues. These are amplified a thousand-fold when your remake is targeted at children.

Children, for better or worse, are little sponges, and parents have never been more anxious about what they’re soaking up. Keira Knightly famously banned her daughter from watching Disney’s 1989 “The Little Mermaid” cartoon film because it quite literally features a teenage girl giving up her voice in exchange for a shot with the man she loves (a man who, Knightly pointed out, she’s “only seen dance round a ship and then drown”). The wicked stepmother trope is somewhat awkward in our enlightened new world of blended families, and it’s impossible not to notice how regularly a Disney prince’s crowning moment is kissing a maiden while they’re sleeping.

This is where Dahl-based content can be tricky. He understood that children were drawn to darkness, but what was acceptably edgy a few decades ago might be considered repugnant now. Anne Hathaway, who played the Grand High Witch in “The Witches” (2020), which was based on Dahl’s 1983 book, was moved to apologize for the film’s portrayal of people with limb differences.

The random cruelty meted out not just by Dahl’s villains, but his heroes, reads differently on the big screen, and that discomfort has amplified over the years. It was one thing to see Wilder’s Wonka merrily send Augustus Gloop up a pipe in 1971. But Depp’s dead-behind-the-eyes Wonka uttering “I invited five children to the factory and the one who was least rotten would be the winner” was chilling.

So, how to revisit beloved characters without reviving their outdated values as well? Sanitized reprints of books under the original authors’ names do everyone a disservice, and it’s similarly disingenuous to repackage those stories for the big screen and pretend they were politically correct all along.

But remakes are reliable money spinners in Hollywood, and when they’re aimed at kids, there’s huge pressure to get the tone right. This often means adding new bits to balance out the old, problematic stuff, with haphazard results. Emma Watson’s Belle in Bill Condon’s “Beauty and the Beast” (2017) couldn’t just be into reading, she had to have a back story. Cue ponderous interludes in plague-ridden Paris. Ritchie’s already-gauche “Aladdin” needed more than one female character. Enter Jasmine’s narratively irrelevant new handmaiden. This anxious padding might help filmmakers sleep better at night, but it isn’t necessarily more enjoyable to watch.

This is why the “Wonka” strategy is so brilliant. By lifting the best bits from the book but remaining unencumbered by its story, it leaves its creators free to create their own magical world without tying themselves in knots trying to make old ideas align with modern sensitivities. Echoes of the 1971 film are sprinkled here and there, but only when they serve the story. Nothing’s shoehorned for the sake of completion, nothing’s jostling for space alongside “must-have” elements of the original.

In a moviemaking world where new ideas are always riskier than tried-and-tested hits, this feels like a middle ground that guarantees box office success, while offering audiences something new. No effort is made to explain how this younger, happier Wonka morphed into the deceptive misanthrope we know from “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” — and honestly? I hope it never is.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com