As opioid epidemic rages on, US jails may be getting some help from state Medicaid funding

As the country's opioid epidemic kills tens of thousands of Americans each year, some of those most at risk – the incarcerated – may soon be getting some help.

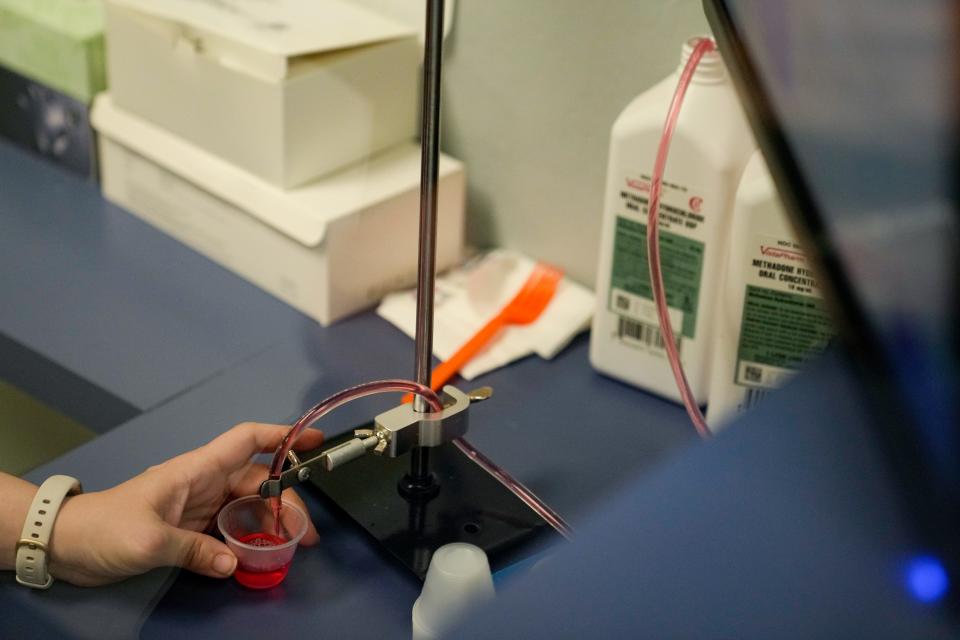

States will be allowed to use Medicaid to pay for drug treatments for people in jails and prisons under new federal guidelines announced last month.

"We think that it's wonderful news," Maria Morris, a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union's National Prison Project, told USA TODAY. "These are medical conditions and they require medical treatment."

Only about 10% of people with an opioid use disorder get treatment, according to medical researchers at New York University who study addiction.

The treatment rate is even lower among the incarcerated, who are at a higher likelihood for a fatal overdose upon release from prison, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Opioid use common as people enter prison

Since Medicaid was established in 1965, federal law has prohibited money from the program being spent on inmates, meaning low-income people who were on Medicaid outside of prison have had their coverage cut while incarcerated.

The new federal guidelines are a welcome change and could make inroads in combatting the opioid crisis, drug treatment advocates say.

The surging opioid epidemic and high rates of substance use disorders among incarcerated people are deeply intertwined, said Joseph Friedman, a substance use researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles.

"Incarceration is one of the key risk factors driving the overdose crisis," he said.

Four main factors converge to create a higher risk of fatal overdoses for former inmates in the "immediate period" following release from incarceration, Friedman said.

Because the U.S. harshly criminalizes illicit drugs, a high number of incarcerated people enter U.S. prisons with opioid use disorders, Friedman said.

Inside prisons and jails, inmates are "cut off from their social networks on the outside" and aren't able to learn how illicit drug supplies have rapidly gotten more dangerous, he said.

If an inmate is not using drugs in jail, their tolerance for the substance will decrease substantially, making them much more vulnerable to overdosing upon release, according to Friedman and Morris.

Discrimination in housing and employment against former inmates fuels economic instability, Friedman said, and the resulting financial stress is a "big part of what breeds overdoses" among people released from prison with untreated opioid use disorders.

Treatment would help fight opioid epidemic

There were 107,622 drug overdose deaths in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and two-thirds of those deaths were caused by fentanyl, a highly potent synthetic opioid.

If treated with medication for their opioid use disorder while inside prison, former inmates are around 75% less likely to fatally overdose upon release, the ACLU says.

"If you are not treating people's substance use disorders, then they are going to do what they need to do to deal with their addiction," Morris said. "And that is generally going to be illicit drugs, and as a result, there are large numbers of people who are overdosing."

In the February Medicaid announcement, Dr. Rahul Gupta, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said treating the issue in prisons and jails is a good idea.

“It's a smart move for our economic prosperity, for our safety and health of our nation," he said.

Gupta also announced that by summer all federal prisons will be offering medications to treat substance use disorder.

Drug treatment among incarcerated could help keep them out of prison

Researchers who study drug use disorders among the U.S. incarcerated population say treatment in prison will help reduce recidivism – when a released criminal commits crimes again.

Last year, the National Institute on Drug Abuse released findings showing Massachusetts inmates with opioid use disorder treated with Buprenorphine were 30% less likely to get re-arrested in the first year compared to inmates with the disorder who did not receive treatment in a neighboring county.

When "this very high need population" returns to their communities upon release, the government should want them "to be coming back healthy and productive and less inclined to return to prison," Morris said.

Contributing: Associated Press

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Opioid crisis in US breaches prison walls as inmates battle addiction