'Oppenheimer' and the Manhattan Project as remembered by an FSU professor who was there

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

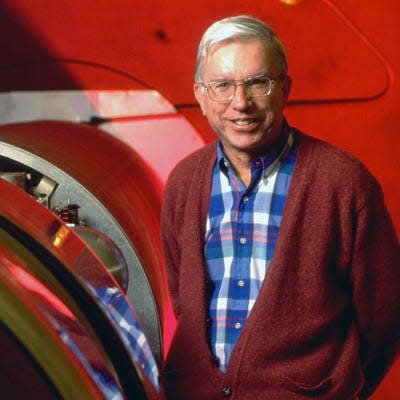

A revered Florida State University professor and chemist worked on the nation’s top-secret Manhattan Project that made the first atomic bomb during World War II — an experience tied to the recent release of the popular Oppenheimer movie.

Raymond K. Sheline, who passed away in 2016 at the age of 93, was a member of the project along with Julius Robert Oppenheimer himself — who directed the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico during the initiative.

Sheline even knew Oppenheimer well enough to share what his temperament was like when speaking to others.

“Most people, when they want to impress you, they get excited and they speak louder and louder. Oppenheimer did precisely the opposite,” Sheline said during a recorded 1995 colloquium session in Florida, where he discussed his involvement in the project. “If he wanted to make a point, he lowered his voice so that everybody would lean forward to be sure to hear what he was saying.”

“He had an amazing ability to get along well with people,” Sheline added. “He sort of held them in the palm of his hands, almost.”

The well-received movie "Oppenheimer," directed by Christopher Nolan, came out July 21 and explains the life and struggles of the man known as the “father of the atomic bomb” as he was responsible for the research and design of an atomic bomb during the Manhattan Project, which spanned from 1942 to 1945.

The creation of the atomic bomb led to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, killing over 200,000 people, to avoid a U.S. invasion of Japan and cut the war in the Pacific short.

In his speech, Sheline admitted to feeling a lingering sense of guilt of the bomb's toll.

"It’s easy to rationalize: we saved lives by dropping these two bombs and killing 250,000 people. Because if we’d had to go from island to island and invade the homeland of Japan, it’s hard to say how many lives would have been lost?" he asked.

2023 Oppenheimer movie: Exclusive footage: Why Christopher Nolan's 'Oppenheimer' is 'the most important story of our time'

More: The 'Barbenheimer’ phenomenon: How a movie meme inspired the 'crazy, weird' double feature

Sheline, who was a Port Clinton, Ohio, native and an Army veteran, received an invitation from chemist and Nobel Prize winner Harold Urey to join the project in 1943 — during his early 20s — after he graduated first in his class with a bachelor’s degree in physics from Bethany College in West Virginia.

“He was a brilliant scientist, and he wasn’t even in graduate school at that point,” Mark Riley, FSU’s Raymond K. Sheline Professor of Physics, told the Tallahassee Democrat.

“You don’t get asked to be a part of that project at his young age without being an amazingly gifted scientist,” he added.

Riley, who has been holding the professorship title for over 20 years and now serves as dean of FSU’s Graduate School, says Sheline was one of his biggest mentors at the university and described him as a “marvelous inspiration.”

Other FSU news: FSU professor fired; provost says research 'negligence' caused near 'catastrophic' damage

Sheline worked on the project at Columbia University with a focus on gaseous diffusion before moving on to work on it at Oak Ridge and Los Alamos. He did not witness the test that took place 210 miles to the south.

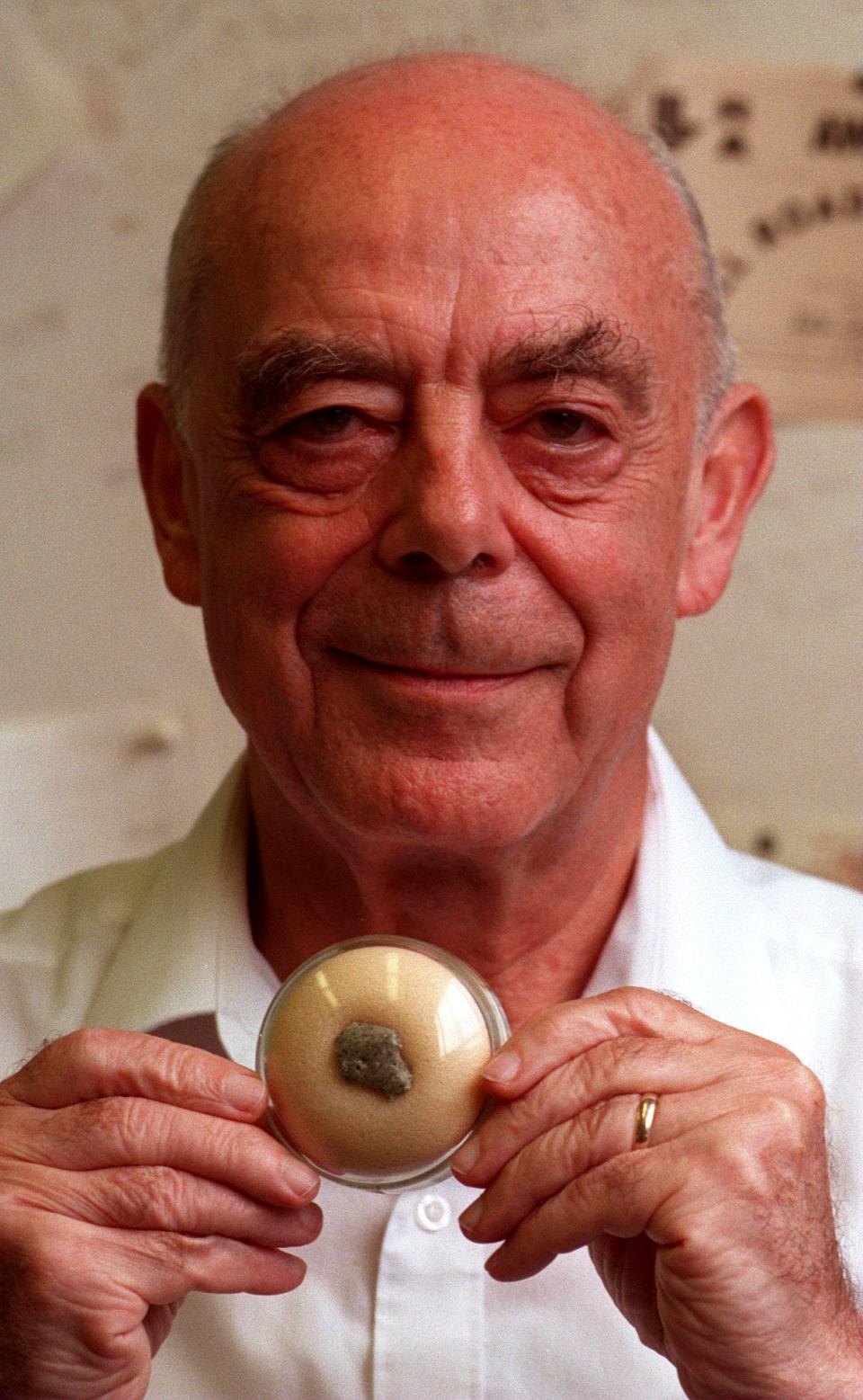

"I arrived there, as it turns out, just two days before the test of the first atom bomb at Alamogordo," he said during the 1995 speech. "I can show you samples of the glass that were produced when the first atom bomb was exploded in Alamogordo on the sand of the desert. It’s sort of a glass, coming from the tremendous heat of the atom bomb."

He then earned his doctoral degree in chemistry from the University of California at Berkeley in 1949, and in 1951 he joined FSU, where he taught for nearly 50 years.

He is also highlighted for growing the experimental nuclear physics group at FSU, which has been performing world-class science for decades.

“Ray was a brilliant experimentalist and did a fantastic job when he came to FSU, in terms of running a very fine physics program,” said Kirby Kemper, 83, a former FSU physics professor who retired in 2012 as Vice President for Research.

Some of Sheline’s other accomplishments included publishing more than 400 scientific papers and helping to establish a nuclear chemistry lab at the Niels Bohr Institute in Denmark, where he was offered a permanent position by physicist Niels Bohr himself but declined to continue teaching at FSU.

Sheline also served as FSU’s Robert O. Lawton Professor of Chemistry and Physics at FSU and over 50 graduate students got their doctorate degrees under his direction, according to a 2014 article written by his son Johnson Sheline — one of the seven children he had with his late wife Yvonne Engwall Sheline, who received her doctoral degree in education from FSU.

Reflection of Sheline's life: Son reflects on his father’s life

As Riley reflected on Sheline’s legacy, he mentioned that the “spectacular” Oppenheimer movie gives a real sense of how significant the Manhattan Project was, and he believes it will win a number of Oscars in the future.

He says he watched the film at the Challenger Learning Center of Tallahassee’s IMAX theater with Provost James Clark and some of his nuclear physics friends, including Kemper.

“We’re excited to be able to show this epic film at the Challenger Learning Center in IMAX, the way that Christopher Nolan intended it to be seen,” the Center’s Executive Director Alan Hanstein said.

The Challenger Learning Center’s IMAX theater, which is open to the public and located on South Duval Street, will be showing the film until Aug. 16.

Contact Tarah Jean at tjean@tallahassee.com or follow her on twitter @tarahjean_.

FSU Professor Sheline remembers the Manhattan Project in his own words

In a 1995 speech at FSU preserved as an oral history by the Atomic Heritage Foundation's Voices of the Manhattan Project, Florida State University professor Raymond K. Sheline shared some key moments.

On the secrecy of the project

"There was incredibly intense security. The main way that security worked was, they had each little group with its own particular problem working. But there was no contact between any of those groups so that nobody knew, really, what they were doing. We didn’t know what we were doing at all for a long time. There were all sorts of weird rumors. Finally, the head of our group illegally told us what we were doing."

On Gen. Leslie "Dick" Groves, played by Matt Damon in the movie

"He was really a military man, and he thought he would treat scientists just like the military people. But little by little, he found out that wouldn’t work. I remember — which shows how immature I was in some way — a group of us in the Tech Area, where it was illegal to salute, because it was dangerous. You might be carrying radioactive material around or something. A group of us lined up in a line and marched right up to General Groves and did not salute. After the war, General Groves got his way. As soon as the Japanese surrendered, all of sudden, we had inspections and all the fol-de-rol of being in a real Army."

On the mindset of scientists working on the project in a race with Hitler

"They worked extremely hard, probably 60 hours a week or more. The reason was that we were convinced that Hitler had a good chance of getting there first. In fact, Hitler was making speeches all the time, and we were hearing what his speeches said. Hitler was saying, “I have a much more destructive weapon,” and they were sure he was talking about the atom bomb. But in fact, he was really talking about the V-2, the rocket bombs. They never really came that close [to developing an atomic bomb], as we found out after the war. But, at the time, as far as we knew, he might be very close."

On whether to use the bomb on a deserted island or Japan

"The decision had to be made on whether or not to drop the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Certainly, some of the scientists at Los Alamos — I was among them — preferred that we try and to have a demonstration on a deserted island to show the Japanese the force of the atom bomb, in the hope that they would then surrender. However, what I didn’t know – and I think most of my colleagues there didn’t know – is, at that time, there were only two or three atom bombs available."

On the challenge ahead when faced with global suicide

We are getting close to the time when we really could commit global suicide. But you say to me, “No one would do this. Who would want to commit suicide? That’s absurd.” But think for a second about Hitler hiding under Berlin at the end of World War II. He was already committed, I think, to suicide. I believe that he would have taken a sort of perverse joy in taking everybody with him if he could have."

"In the scientific realm, we can expect our students to climb on the backs of a Newton or an Einstein... and go on from there to greater heights in science. That is because science is a rational kind of structure. However, in the realm of ethics and morality, we cannot climb on the backs of a Jesus or a Mohammad or a Gandhi. We cannot be handed our morality on a silver platter, the way our greatest scientists have handed us their knowledge."

"This, then, achieving the kind of morality that can allow our world to continue, is our greatest challenge."

Never miss a story: Subscribe to the Tallahassee Democrat using the link at the top of the page.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Late FSU professor Sheline worked on Manhattan Project with Oppenheimer