Oppenheimer, Miyake, and Sierra Hull: Fission, Fashion, and the Future of Bluegrass

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As I write this, it is early evening on Aug. 6. Hiroshima Day. If your brain is nimble enough, and if your soul is still intact after the last four years, imagine the stillness of this evening hour 78 years ago, in a city about the size of Knoxville, on a south-facing harbor at the western extremity of Honshu Island. It was the day of Two Suns. There was the sun that rose from the icy North Pacific. And then there was the one that dropped out of the Enola Gay.

With J. Robert Oppenheimer’s face, or his Hollywood stand-in’s, gazing blankly from every bus stop in New York City and from my smartphone at the most unexpected turns of the day, and with his bio-movie racking up huge profits as this dreadful day passes meekly by once again, I’ve been thinking about The Bomb more than I usually do, which, as a born-and-raised Oak Ridger and a son of one of K-25’s ingenious instrumentation engineers, is disproportionate to the general population’s attention to history. To this history,

I haven’t seen the movie. The Movie. “Oppenheimer” And I’m not feeling compelled to go, either by historical involvement or current geopolitical insecurities. I’m also not feeling compelled to see “Barbie.” I do have a physical ticket to “The Sound of Freedom” folded in my wallet, and I’m trying to figure out when I’ll have time to see that film, because every day there are news stories about pedo-predators, and the so-called “border crisis” seems to be significantly fueled by pedo-predators. It’s worldwide. Today there’s a story about a baker’s dozen of Australians who were just busted for trafficking in children-for-sex after an American suspect in their network killed two heroic FBI agents. But who wants to hear about that, when you can see a movie with scenes of J. Robert Oppenheimer having sex, or trying to anyway. “I am become Death,” the naked J. Robert mutters. Indeed. This movie redefines “nerd” like The Bomb redefined collateral damage.

On the eve of Hiroshima Day, there was a pop-up stand at the farmers’ market in Jackson Square manned by a park ranger for the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, at which one could decorate a brown paper lunch bag for the next morning’s luminary remembrance of the obliteration of Hiroshima, the only way Japan could be convinced to stop their pathological national killing spree in 1945. The ranger, who couldn’t have been older than 25, had the closest copy of Charlie Chaplin’s "Little Tramp" mustache I have ever seen, and there was something about his spiel that was absolutely laughable. But my kids were interested in the lunch bags, with the thought of decorating them so they could be lit up from within by tea candles the next morning before sunrise, before the second sun rise.

So they drew pictures of the Little Boy, then made red circles around them with a slash through the middle, to say "No More Bombs."

I inscribed a lunch bag to my parents’ memories. And another to a friend who died in 2020. His name was Issey Miyake.

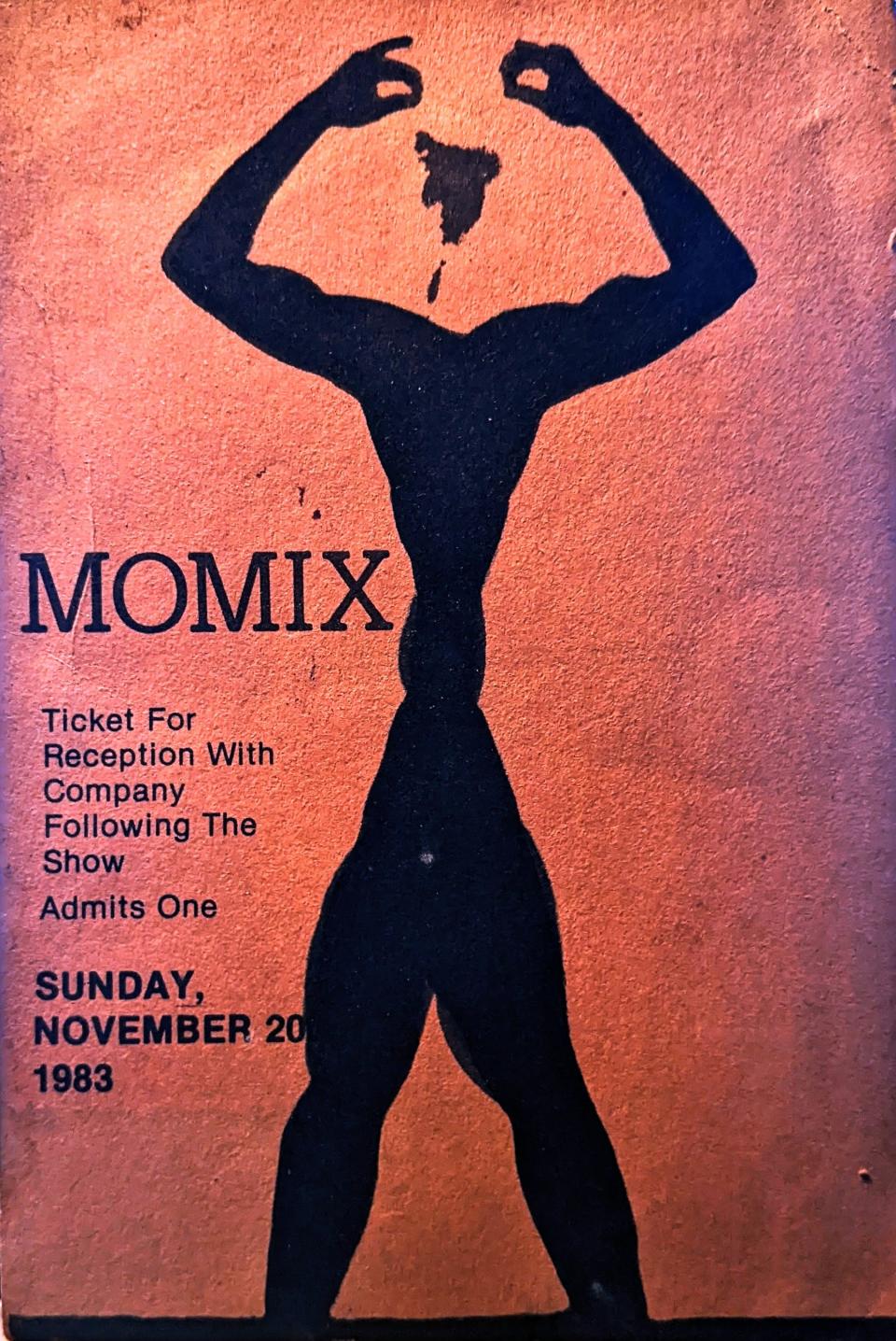

Issey Miyake was born in 1938. I met him in 1983 in Berkeley, California. He was a break-out phenomenon in the world of fashion design and had been featured on the cover of ArtForum Magazine in 1982, the year my dance group MOMIX had also begun making a name for itself.

In November ’83 (good Lord, it’s 40 years ago), I produced one of MOMIX’s most successful forays to the artsy Mt. Olympus of West Coast intelligentsia, Berkeley, and its one-of-a-kind temple of the avant garde, the Julia Morgan Theater.

The poster I made for this gig featured a silhouette that became the signature graphic image for MOMIX, a silhouette that came from a fascination I had with silhouettes scorched into the sidewalks and onto the walls of the few buildings that weren’t flattened by the Little Boy. They were the most perfect artistic representation of human souls I could imagine. A person, vaporized, immortalized, mid-breath.

During the week of MOMIX’s engagement at the Julia Morgan, Issey Miyake was in San Francisco with an exhibit of his latest fashion creations, built around the stunning form of Grace Jones mannequins. The exhibit, at the old SF Museum of Modern Art, was called “Bodyworks.” Grace Jones in feathers. Grace Jones in mid-air. Grace Jones in pleated fan-like wraps. It was the most stunning artistic statement I had ever seen. It was so pure, it simultaneously took your breath away and made you shed tears. And the day after I visited Miyake’s show, he came to see MOMIX in Berkeley. Next thing I knew, he sent us tickets to Tokyo, where we performed in several theaters on two visits in 1984, from that city’s most avant garde showcase, Sagacho Exhibit Space, to the more traditional stages in Shinjuku.

On our first trip to Tokyo, I was in a taxi with Issey and he asked me about where I came from. So I explained Oak Ridge, that it had been a secret city during World War II where the critical workings of the Atomic Bomb had been fabricated. He was silent, completely still as the taxi raced through Roppongi. We stopped in front of Sagacho Space, and as we walked to the front door he said very softly ,“I was born in Hiroshima.”

Up 'til then, I had known Issey for his two loves in this world. People, and the human form. But quietly and suddenly, something akin to black light came on.

Miyake was 7 years old on Aug. 6, 1945. He told me that, as an adult, he wanted to be known as a creator, not as a survivor, so that morning was not something he talked about. But he had been there. He had a pronounced limp from a bone marrow disease from radiation exposure. His mother died of radiation sickness. Not instantly like a silhouette scorched into a sidewalk. No, her death came three years after the initial Hiroshima Day.

Miyake didn’t make his connection to that day widely known until he was 71 years old. He wrote a short piece in the New York Times in 2009, inviting Barack Obama to bring other world leaders to walk across Hiroshima’s Peace Bridge, to pledge an end to nuclear weapons. Thirteen years later, Miyake passed away without a response from Barack Obama. And Christopher Nolan, director of “Oppenheimer,” probably never heard of Issey Miyake.

Sierra Hull performs Saturday in Oak Ridge

Meanwhile, back on the brighter side of the Secret City, Sierra Hull will be playing Saturday evening at A.K. Bissell Park for the ORNL-FCU’s final Summer Sessions concert. It’s been two years since she played her first Summer Sessions show, when she asked her band plus the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys and the then 12-year-old Wyatt Ellis to follow her off the stage and into the crowd for a jam session that drove a stake through the heart of the myth of social distancing.

Will Wyatt Ellis make another appearance with Sierra Hull? No one knows, but the two of them have a new video just out since mid July called “Grassy Cove.” And it perfectly illustrates why bluegrass is the healthiest of all genres of contemporary American music. Like Wyatt, who is now 14 and playing with the greatest instrumentalists of our time like Michael Cleveland, Billy Strings, C.J. Lewandowski, and Sam Bush, Sierra also picked up the mandolin when she was 10. Now going on 32, she embodies the model of the perfect mentor, and she lives something Ricky Skaggs said: If you can play bluegrass, you can play anything. For the sweetest proof, listen to Sierra Hull’s duet “Sweet Sixteenths” with the amazing banjo virtuosa Alison Brown, or her duet “Chasin’ Skies” with the fiery Tessa Lark.

Just remember, this is the last Summer Sessions show, a special celebration of the Credit Union’s 75th Anniversary, and it starts at 4 p.m.. Will the series return in 2024? I sure hope so.

Ever heard a song called “All The Hay’s In The Barn”?

John Job is a longtime Oak Ridge resident and frequent contributor to The Oak Ridger.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Fission, Fashion, and the Future of Bluegrass