'Oppenheimer' is a movie hit. But this Florida man saw REAL atomic bombs blow up

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Everyone’s been lining up to see the movie “Oppenheimer.” But not John Siko.

When it comes to nuclear explosions, the south Fort Myers resident has seen the real thing.

Four times.

“People talk about Oppenheimer. Hell, I’ve seen more than he did!” Siko says and laughs. “Why would I want to see that?”

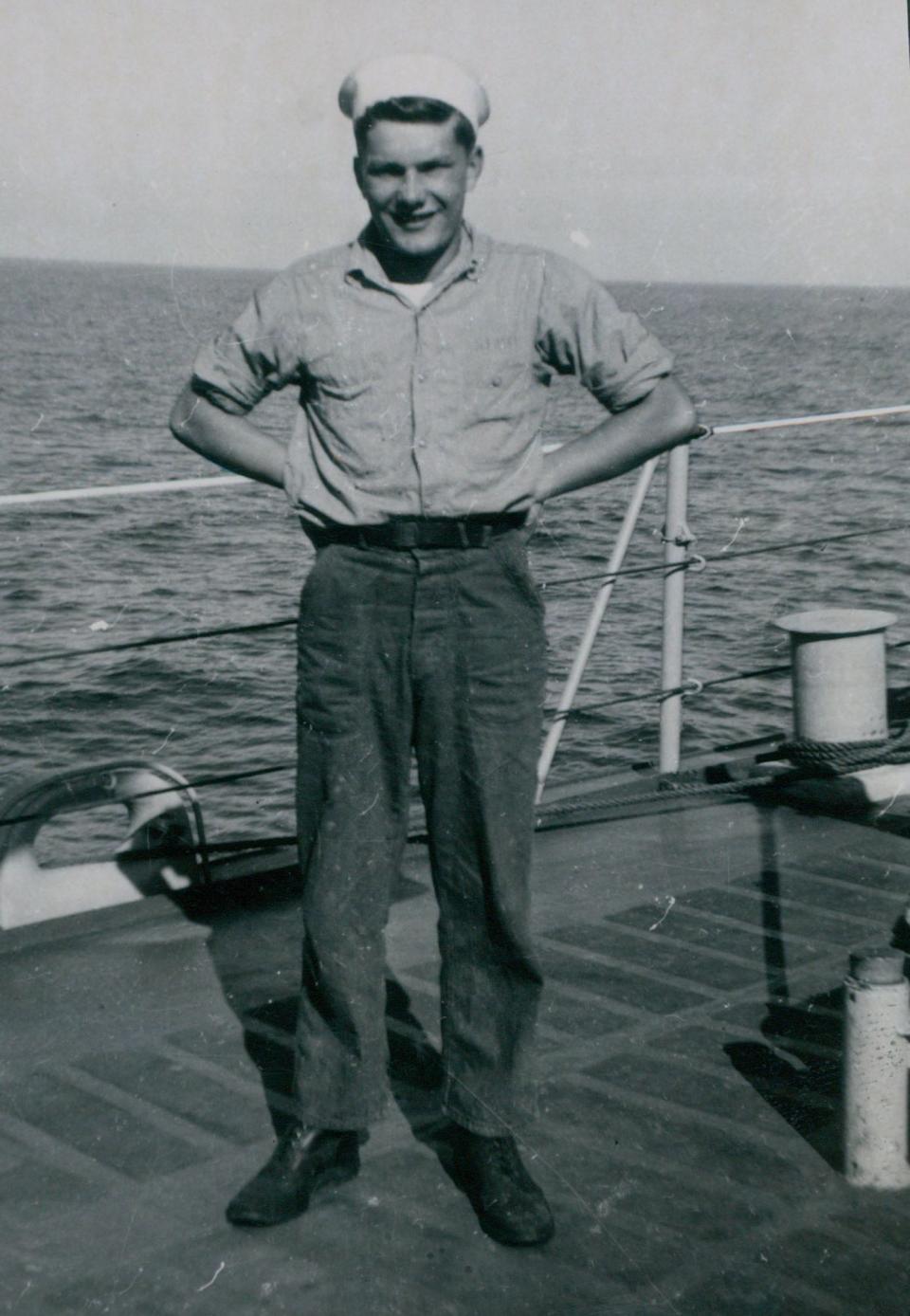

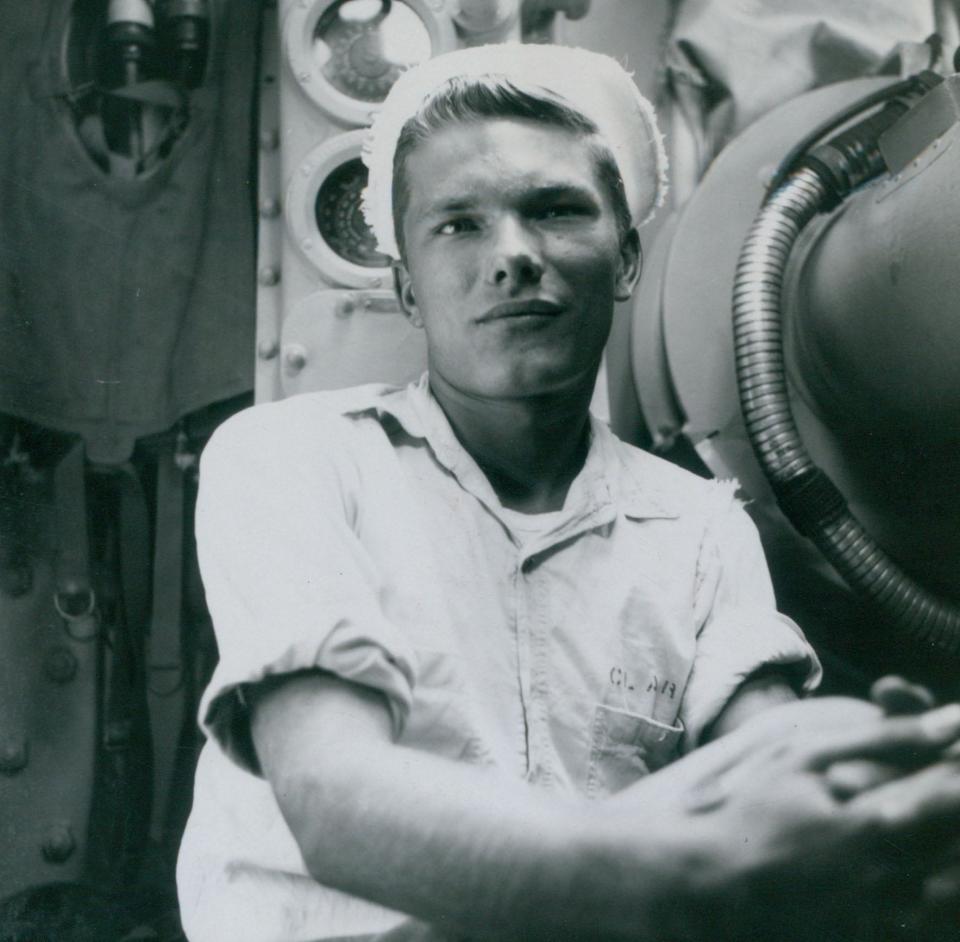

Siko, 90, was a U.S. Navy seaman on the USS Walker during the Korean War. He’d signed up right out of high school in 1950, and his first deployment took him to the Marshall Islands in March 1951.

Their secret mission: Exploding four nuclear bombs to figure out how to reduce the size and increase the destructive power of future thermonuclear weapons. The tests later became known as Operation Greenhouse.

Physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer famously regretted his role in creating the world’s first atomic bomb in 1945. Siko admits he didn’t have that luxury when it came to Operation Greenhouse.

“He had a choice,” he says. “I didn’t. … It’s part of your duty there.”

Still, Siko knew he was taking part in something momentous.

“At the time, we knew it was history because it was so classified,” he says. “We were witness to something that, in many years, could be destructive to the world, you know?

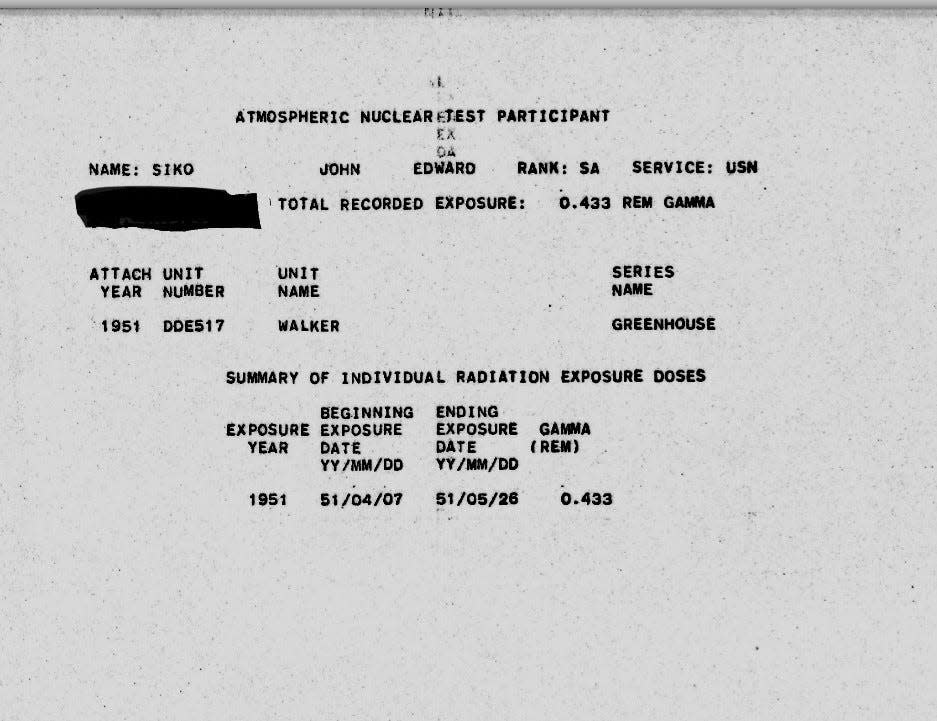

People don’t always believe Siko ― pronounced SEE-ko ― when he tells them the story. But he’s got the official paperwork showing he was there and exposed to gamma radiation from the blasts: Approximately .433 rem (a measure of the radiation dose) between April 7 and May 26, 1951.

Was he scared at the time?

Nah, he says. He was young and felt invincible.

“When you’re 18 years old, you don’t think about those things,” he says, chuckling as he sits in the living room of his south Fort Myers villa. “You’re gonna live forever anyway.”

The secret mission: No cameras allowed

The USS Walker was Siko’s first assignment right out of boot camp. The World War II destroyer had been “mothballed” for years, he says, but it was recommissioned for the Korean War.

Siko was one of 265 men onboard. His job was a “deck ape”: Working on the ship’s top decks and doing things like repainting or cleaning the deck with a firehose.

Before they left their home base at Pearl Harbor, the crew was told they wouldn’t be allowed to take cameras onboard, Siko says. And they wouldn’t be able to write home for the length or their deployment.

But it wasn’t until they’d anchored in the Marshall Islands ― a chain of about 1,225 islands in the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Australia ― that they were told why they were there.

“We were told that they would be conducting atomic warfare tests,” Siko says.

Siko knew all about atomic bombs, of course. Oppenheimer had helped develop the first A-bomb for the United States during World War II ― the subject of the hit summer movie “Oppenheimer” ― and the resulting weapons ended the war when they were dropped on two Japanese cities in 1945.

But again, he insists he wasn’t scared.

It was a new adventure.

“Well, I looked forward to it,” he says and laughs. “It’s not something that the average person is going to get the chance to see.”

The tests: ‘Everything is gone.’

The USS Walker and its sister ship, the USS Spronsen, were in the Marshall Islands to keep other vessels out of the 50-mile-wide testing zone, Siko says.

Fishing boats from Japan and other countries would often pass into those waters, he says. The Walker crew would warn them off with a bullhorn. Or, if the people didn’t understand, a warning shot.

They also hunted for Soviet Union ships and tried to jam their radio communications so the Soviets couldn’t intercept transmissions about the nuclear tests.

The bombs were mounted atop 200-300-foot steel towers on four of the small islands in the Enewetak Atoll. Siko could see the towers while the Walker patrolled around the Marshall Islands. He could also see the quickly-constructed buildings designed to test the effect of the blasts on manmade structures.

Later, all those buildings would be obliterated ― along with much of the islands they’d stood on.

“Everything is gone,” Siko says. “You’d see a flat island. Still dusty. The dust just hung around for a long time.”

After each blast, Siko’s job was to help hose off the USS Walker's decks to remove any radiation. But he acknowledged that only went so far.

“The problem is, there’s a lot of fiber aboard ship,” he says. “You have canvas and you have lines. They’ll absorb radiation. You really can’t hose it off.”

If there was any fear, he admits, it was over the wind blowing back more radiation from the bombs onto the USS Walker.

“Wind is a big deciding factor, and there’s nothing to control the wind,” Siko says. “Wind can change direction at any time.”

Four nuclear blasts: 3-2-1, then orange light everywhere

Siko says he never saw the actual moment of detonation for those four bombs. Only the officers, wearing welder’s glasses, could stare directly at the explosion.

Like most of the crew, he had to look away to protect his eyes.

“You have to turn your back,” he says. “You can’t face it.”

For each explosion, the Walker would be floating in the Pacific Ocean about four or five miles from the blast site. You couldn’t even see the test towers and buildings from that distance.

Each imminent explosion would be announced on the ship’s loudspeakers: “One minute til blast.”

Everyone would stop what they were doing, wherever they were on the ship, and get ready to turn their backs.

At 10 seconds, the loudspeaker would start counting down: “10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.”

Then it happened.

First came the light. The early-morning sky would brighten all around him, orange light everywhere. “It was like the sun rising,” Siko says.

Then, almost immediately, came a wave of heat. Not boiling heat, but definitely warmer.

“It came through quick,” Siko says. “You could feel it, but then it was gone.”

Finally, a few seconds later, came the boom. Or what was left of the boom, anyway.

“It’s sort of a muffled roar,” Siko says. “It’s not like TNT going off. Because, again, it had three miles to dissipate.”

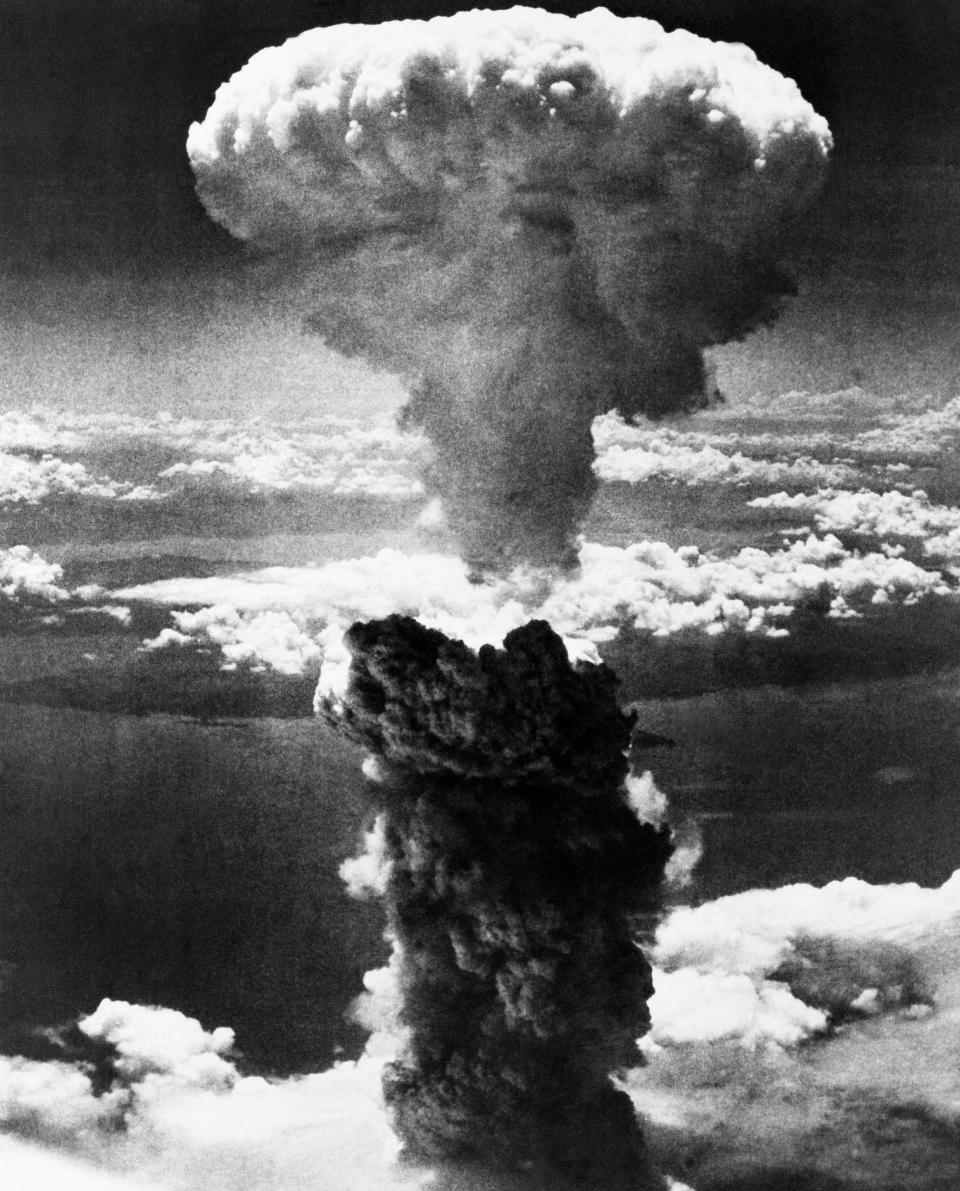

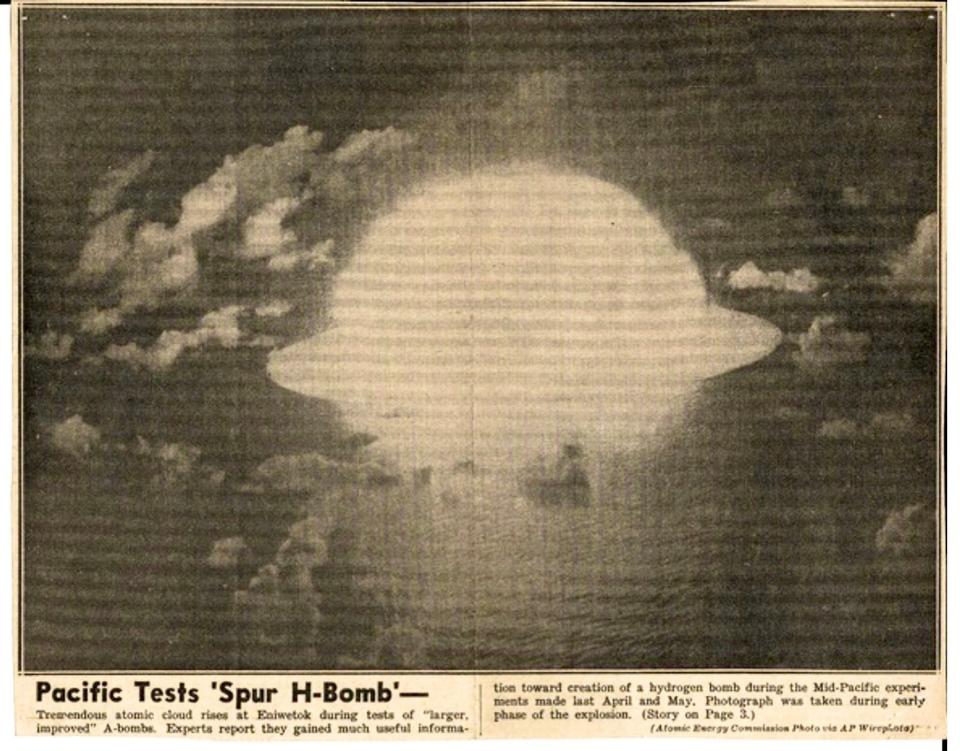

The whole thing lasted only a few seconds, he says. Then everyone could turn around and see that telltale mushroom cloud ― just like the ones people have seen in “Oppenheimer” and countless other movies.

The cloud would rise up into the sky from the island: A long stem made of ash and smoke, topped ― about 1,000 feet up and rising ― by an expanding, mushroom-like cap.

Siko could still see remnants of the initial explosion ― the glowing orange of flames inside the stem of that oversized mushroom ― for maybe 10 seconds.

“By the time you turn around, the fire portion of it is already enveloped in dust,” he says. “You’re looking at the blast through the dust. It was like looking at the sun through the fog.”

The cloud would continue to rise up into the sky, all the way to about 25,000 feet, he says.

So what did Siko feel in those moments? Awe? Fear?

“No,” he says and laughs. “You just feel, ‘It’s all over. Is that all there is?’”

When pressed, Siko admits it was kinda cool and impressive.

But this was the U.S. Navy, and he didn’t have time to dawdle and ponder what he’d just seen. He had a job to do.

Those radiation-washed decks wouldn’t clean themselves.

“It almost got to the point of, ‘Oh, OK, that’s really something to be witnessed and everything,’” he says. “But then you went about hosing down the ship.”

Life after Project Greenhouse, memories rekindled by 'Oppenheimer'

After that momentous experience, Siko spent two more years in the Navy with ports of call in Hong Kong, Formosa (now Taiwan) and mostly Hong Kong.

Then, after three years of service, he was discharged at the rank of DK3 (Disbursing Clerk Third Class) in December 1953. He went to college on the GI Bill and worked a series of manufacturing jobs, including a plant manager for an RJR Nabisco/Del Monte plant in Buffalo, New York.

But 72 years after the Marshall Islands, Siko still proudly wears a baseball cap that says “TIN CAN NAVY.” “Tin can,” he explains, refers to Navy destroyers like the USS Walker.

Until recently, he didn’t talk much about Project Greenhouse. But he’s been doing it more often these days, thanks to the movie “Oppenheimer,” one of the biggest blockbusters of the summer.

The movie even inspired him to write down his story on paper so he could hand it out to his family and golf buddies. Although he admits it wasn’t always easy recalling the details.

“It was 72 years ago,” he says. “It’s hard to imagine, but that’s how long it’s been.”

As far as all that radiation, Siko says he hasn’t had any negative health effects from the exposure ― at least that he knows about.

“I glow at night,” he says and laughs. “That’s about it.”

Connect with this reporter: Charles Runnells is an arts and entertainment reporter for The News-Press and the Naples Daily News. For news tips or other entertainment-related matters, call him at 239-335-0368 (for tickets to shows, call the venue) or email him at crunnells@gannett.com. You can also connect with him on Facebook (facebook.com/charles.runnells.7), X (formerly Twitter) (@charlesrunnells), Threads (@crunnells1) and Instagram (@crunnells1).

This article originally appeared on Fort Myers News-Press: 'Oppenheimer' is about atomic bombs. This man saw the real things explode