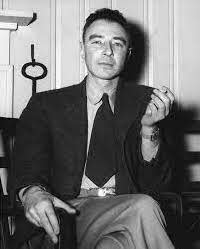

Oppenheimer and Nichols: A changing relationship

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Carolyn Krause brings us the second and final part to her series on J. Robert Oppenheimer which she presented to the Oak Ridge Heritage and Preservation Association’s public meeting on May 24, 2022.

***

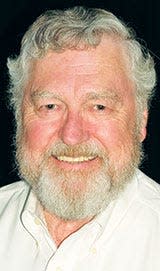

One evening in Oak Ridge in the fall of 1943, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific director of the Manhattan Project, joined Colonel Kenneth Nichols and his wife Jackie for dinner and gifted them with small Mexican brandy glasses. A few weeks earlier, in May, Nichols had been named second in command to General Leslie Groves, the military director of the Manhattan Project; Nichols’ title was District Engineer of the Manhattan Engineer District, and he was responsible for overseeing the construction and operation of the nuclear fuel production plants at Oak Ridge and Hanford, Wash. At the time, Nichols and his wife lived at 103 Olney Lane.

Oppenheimer visited Oak Ridge several times. At least once he visited his younger brother Frank, a physicist who was sent to Y-12 from Berkeley, Calif., in 1944 and 1945 to monitor the operation of the calutrons used to enrich uranium in the U-235 isotope. Frank and his wife were both atheists and members of the Communist Party of America at the time.

Nichols learned what Groves knew when he made the controversial decision in 1942 to appoint Oppenheimer scientific director: that Oppenheimer had associations with known and unknown communists (e.g., his brother, his wife Kitty, and several students) and had made contributions to the Communist Party of California but was not a party member.

The Soviet Union was an ally during the war, but some Army officials regarded Oppie as a security risk. Groves discounted these facts and ordered the Army to give Oppenheimer in 1943 his security clearance – access to classified information. Shortly after its formation, the Atomic Energy Commission renewed it in 1947 and thereafter. Upon meeting with Groves and Oppenheimer on a train, Nichols was confident that Oppie was the right man for the job. He never regarded him as a spy, source of technical information to the Soviet Union or disloyal American citizen.

Even so, 10 years later, when Nichols was general manager of the Atomic Energy Commission, his attitude toward Oppie shifted. He learned that President Eisenhower had ordered the AEC to hold a hearing to determine if Oppenheimer, then a consultant to the AEC but previously the chairman of its General Advisory Committee, should retain his AEC security clearance.

According to the 2005 book “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer” by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, after Oppenheimer informed Lewis Strauss, AEC chairman, that he would not resign from his AEC consultancy, Nichols “set in motion an extraordinary American inquisition.” What that meant was that he initiated the AEC Personnel Security Board hearing on the loyalty and trustworthiness of Oppenheimer.

The authors continued: “Nichols told Harold Green, on the day the young AEC attorney was drafting the letter of charges against Oppenheimer, that the physicist was ‘a slippery sonuvabitch, but we’re going to get him this time.’

“On Christmas Eve, two FBI agents seized control of Oppenheimer’s remaining classified papers. That same day, Oppenheimer received the AEC’s letter of formal charges, dated Dec. 23, 1953. Nichols informed Oppenheimer that the AEC now questioned ‘whether your continued employment on Atomic Energy Commission work will endanger the common defense and security and whether such continued employment is clearly consistent with the interests of the national security. This letter is to advise you of the steps which you may take to assist in the resolution of this question.’”

In addition to the usual charges about Oppenheimer’s associations with communists and a rejected request that he impart information to a Soviet delegate, he was accused of being “instrumental in persuading other outstanding scientists not to work on the hydrogen bomb project, and that the opposition to the hydrogen bomb, of which you are the most experienced, most powerful, and most effective member, has definitely slowed down its development.”

“The inclusion of Oppenheimer’s opposition to the Super (H-bomb) reflected the depth of anti-Communist McCarthyite hysteria that had enveloped Washington,” Bird and Sherwin wrote. “Equating dissent with disloyalty, it redefined the role of government advisers and the very purpose of advice.”

“The AEC charges were not the kind of narrowly crafted indictment likely to bring a conviction in a court of law. This was, rather, a political indictment, and Oppenheimer would be judged by an AEC security review panel appointed by the chairman of the AEC, Lewis L. Strauss” (who disliked Oppie and his opposition to and delay of hydrogen bomb development during the Cold War when the Soviet Union was an enemy, not an ally).

Oppenheimer, who reacted to the detonation of the first nuclear weapon on July 16, 1945, over the New Mexico desert by uttering the “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds” quotation from the Bhagavad-Gita, opposed the H-bomb on the grounds that thermonuclear weapons were more destructive than mankind could responsibly control. Instead, he lobbied the AEC to work on international arms control.

In his 1987 book The Road to Trinity: A Personal Account of How America’s Nuclear Policies Were Made, Maj. Gen. Nichols wrote that based on Oppenheimer’s testimony, he considered him dishonest but not disloyal. On June 12, 1954, Nichols recommended that Oppie’s security clearance not be reinstated because the five security findings indicated that Oppie was “a Communist in every sense except that he did not carry a party card,” and that he “is not reliable or trustworthy.” The AEC commissioners agreed. Oppie was stripped of his security clearance on June 29, 1954.

After the security findings were issued, Nichols wrote, Oppenheimer’s lawyers “stressed the inconsistency between the board’s findings that Oppenheimer was loyal and its conclusion that he was a security risk. They stressed that if Oppenheimer was a security risk because he had opposed the H-bomb, that would discourage scientists from advising the government in the future. They stressed that the distinguished character witnesses were the best bases for judging his character. They made no mention that Oppenheimer had admitted lying to the security officers.”

According to the website for the Institute for Advanced Study, which Oppie once directed, Hans Bethe recalled that “Oppenheimer took the outcome of the security hearing very quietly, but he was a changed person; much of his previous spirit and liveliness had left him.”

In April 1962, the IAS website stated, “the U.S. government made amends for the treatment Oppenheimer suffered during the McCarthy years, when President Kennedy invited him to a White House dinner of Nobel Prize winners. In 1963, President Johnson awarded Oppenheimer the highest honor given by the AEC, the Enrico Fermi Award. Oppenheimer died of throat cancer on Feb. 18, 1967” at the age of 62.

Although he had amazing achievements as a theoretical physicist, Oppie never won a Nobel Prize. But Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari wrote in his 2015 internationally best-selling book “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” that “The Nobel Peace Prize to end all peace prizes should have been given to Robert Oppenheimer and his fellow architects of the atomic bomb. Nuclear weapons have turned war between superpowers into collective suicide and made it impossible to seek world domination by force of arms.”

***

Thanks Carolyn, for an excellent review of the treatment of J. Robert Oppenheimer. His family continues to work to clear his name. A recent, June 2, 2022, article in Los Alamos National Laboratory’s Discover, entitled, The petition that sought to clear Oppenheimer’s name, https://discover.lanl.gov/news/0602-ribes-petition, highlights the main testimony for and against Oppenheimer holding a security clearance. Lewis L. Strass (most strong advocate against Oppenheimer), Edward Teller, and, General Leslie Groves, were the primary sources against his clearance being renewed. Oppie’s security clearance was revoked one day before it was to expire. Those closest to him said he was never the same after that hearing. He retreated from public life. Lewis L. Strass career was damaged by the result of his attack on Oppenheimer. He was not approved by the Senate for appointment as Secretary of Commerce in 1959, ending a 42-year political career.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Oppenheimer and Nichols: A changing relationship