Who Was The Real Oppenheimer?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, center, is played in Christopher Nolan's new film by Irish actor Cillian Murphy.

Who was Oppenheimer? It’s a question that a lot of people are asking these days, with TV commercials, print ads and billboards constantly promoting the upcoming “Oppenheimer” movie. If you’ve never heard of Oppenheimer, you may well be thinking: “Is this another little-known superhero that Marvel is creating a movie around?” Or you might be thinking: “Who cares who Oppenheimer was? I’m seeing ‘Barbie.’”

But for those who are curious about the man, and wondering what all the fuss is about, here are the answers to all your Oppenheimer questions.

Why are we even asking who Oppenheimer was?

Because he was a very real person who is now getting the Hollywood treatment, courtesy of Christopher Nolan, who wrote the screenplay to “Oppenheimer” and directed the movie.

Nolan’s film debuts July 21, along with — yes, maybe you’ve heard — Greta Gerwig’s “Barbie.” Both movies are expected to be blockbusters.

OK, so who was Oppenheimer?

Julius Robert Oppenheimer was an American theoretical physicist who changed the course of humankind. He’s known as the “father of the atomic bomb.”

He didn’t single-handedly create the bomb, of course. But during World War II, he did manage the U.S. Department of Energy’s Los Alamos National Laboratory, which developed and tested the first atomic bomb. If one person were going to get credit for building the A-bomb, it would be J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Still, as Oppenheimer told the International News Service in August 1945, “No one person should get credit for the achievement — it was a cooperative effort of scientists filled with courage and devotion to their work and to the Allied cause.”

It’s ultimately fair to say that because of Oppenheimer, we have nuclear bombs. It’s really kind of amazing that Oppenheimer hasn’t gotten more attention from Hollywood already, though Dwight Schultz played him in the well-regarded 1989 film “Fat Man and Little Boy.”

What was the Manhattan Project?

From 1942 to 1945, the Manhattan Project was the U.S. government’s top-secret mission to make the atomic bomb. It got its name because in the early days of the project, everybody was working in New York City. Later, the project spread out to facilities in places like Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Oppenheimer and Gen. Leslie Groves (center) examine the twisted wreckage that remains of a 100-foot tower, a winch, and a shack that held the first nuclear weapon in Alamagordo, New Mexico.

Was Oppenheimer smart?

That’s putting it mildly. He studied at Harvard and graduated summa cum laude after three years, in 1925. He went on to do some research at Cambridge, and in 1927, he got his Ph.D. at the University of Göttingen in Germany, where he studied quantum physics. He knew eight languages and enjoyed French literature, art and music.

In 1929, he was offered jobs teaching at the California Institute of Technology and the University of California. He took both positions, going back and forth between Pasadena and Berkeley. After his work on the Manhattan Project, he directed the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton while lobbying for global arms control as an adviser to the Atomic Energy Commission.

So was Oppenheimer a good guy or a bad guy?

There’s not an easy answer for this. Oppenheimer helped make the atomic bomb, but he also helped end World War II.

By many accounts, Oppenheimer was a well-intentioned, complicated and conflicted man, as Nolan’s movie will likely show. He may have not defined himself as a good person. In August 1945, the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima and, three days later, on Nagasaki ― ultimately killing as many as 226,000 people, many of them civilians, and prompting Japan to surrender, ending the war. Even then, Oppenheimer was already second-guessing his role in the making of the bomb.

After the first bomb went off in Japan, U.S. Army Gen. Leslie Groves (played by Matt Damon in Nolan’s film) called Oppenheimer and congratulated him. According to a transcript of the recorded call, Groves said, “I think one of the wisest things I ever did was when I selected [you] the director of Los Alamos.” “Well, I have my doubts, General Groves,” Oppenheimer replied.

In a 1965 NBC documentary called “The Decision to Drop the Bomb,” Oppenheimer famously described the moment in July 1945 when members of the Manhattan Project watched a test explosion that was the first-ever detonation of a nuclear bomb.

“We knew the world would not be the same,” he said. “A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

Still, Oppenheimer didn’t swear off nuclear weapons right away, David Spanagel points out. Spanagel, an associate professor of history at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, said that even after Adolf Hitler was vanquished and World War II had ended ― and there was little reason to keep working on nuclear weapons ― “the group that Oppenheimer led continued to work around the clock to try to bring the atomic bomb designs to fruition and to deliver imminently usable bombs.”

Spanagel said that Oppenheimer offered an explanation of his thinking at the time, if not exactly a defense. “When you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and do it and you argue about what to do about it only after you have had your technical success,” Oppenheimer said of his mindset. “That is the way it was with the atomic bomb.”

“So, in that moment,” Spanagel said, “Oppenheimer made a choice that served the American military and national interest, but he did not question whether it was the right thing to do for humanity because the technical attractiveness of solving the problem preoccupied him fully.”

Still, while Oppenheimer unleashed the world’s deadliest weapon, it seems he was doing what he thought was necessary at the time. As Kayla Green, a chemistry professor at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth who recently taught a class called “How Chemists Win Wars,” put it: “Oppenheimer was human.”

“Patriotism and fear were high during this time of the war,” Green explained. “He, along with scores of other great minds, were pulled into a conflict and pressured to find a solution.”

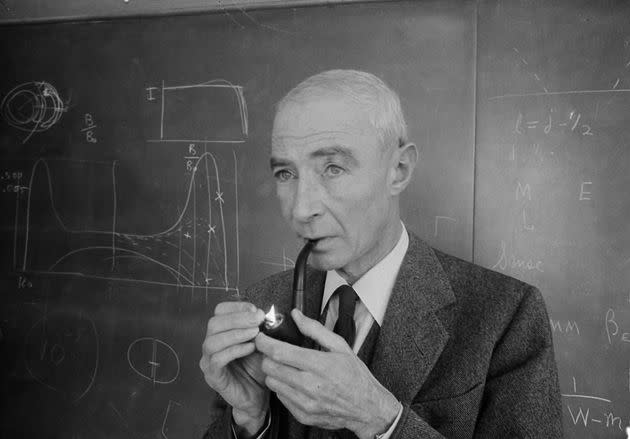

Oppenheimer stands in front of a blackboard in his office at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, April 5, 1963.

“At the end of the war, Oppenheimer pushed for regulations of nuclear weapons,” Green said. “Many of those working on the Manhattan Project recognized that, like chemical weapons in World War I, World War II had unleashed a completely new military approach to wartime. It could not be undone, but could potentially be regulated.”

And Oppenheimer was indeed human. Green noted that he struggled with mental health challenges. He also smoked a pipe frequently, and that likely led to his death in 1967 of throat cancer. He was 62.

President Lyndon Johnson applauds as Oppenheimer turns over to his wife a check for $50,000 during White House ceremonies, Dec. 2, 1963. The check was part of the Enrico Fermi Science Award, presented to the physicist for his work in the nuclear field.

What is Oppenheimer’s legacy?

It depends who you ask. If Oppenheimer hadn’t developed the atomic bomb, it’s anyone’s guess how he’d be remembered today ― or what the world as a whole might look like.

As monstrous a weapon as it is, everybody at the time was afraid the Nazis were going to create the atomic bomb first. History now suggests that Hitler wasn’t spending a lot of time working on nuclear weapons, so some of those fears may have been unfounded. Still, part of Oppenheimer’s legacy is that Hitler never did get his hands on an A-bomb. And some experts argue that we can thank Oppenheimer that, as yet, there hasn’t been a World War III.

“Oppenheimer’s work put an end not just to the worst great power war in human history but, at least so far, an end to all great power war,” said Pat Proctor, an assistant professor of homeland security at Wichita State University and a retired U.S. Army colonel.

“Wars continue to be waged, at generally decreasing scale over the decades, and great powers continue to engage in proxy wars against one another or direct wars against less powerful nations,” Proctor said. “But since the advent of nuclear weapons, for better or worse, the fear of nuclear Armageddon has precluded great powers from engaging in direct warfare against one another. That is arguably Oppenheimer’s greatest legacy.”

That’s one perspective. Certainly the invention of the A-bomb didn’t put an end to countries invading each other, or other atrocities. And if you consider the legacy of the bomb synonymous with the legacy of Oppenheimer himself, a more somber picture emerges. President Barack Obama, during a 2016 visit to Hiroshima, said the memory of the bombing of that city “must never fade.”

“That memory allows us to fight complacency,” Obama said that day. “It fuels our moral imagination.”

In his 1965 nonfiction work “Hiroshima Notes,” the Nobel-winning Japanese author Kenzaburo Oe, who died earlier this year, put it in starker terms. “From the instant the atomic bomb exploded, it became the symbol of all human evil,” Oe wrote. “It was a savagely primitive demon and a most modern curse.”

The first U.S. atom bomb explodes during a test in Alamogordo, July 16, 1945. The cloud went 40,000 feet in the air, as viewed by an automatic camera six miles away from the site.