Orban Frustrates EU’s $30 Billion Effort to Force Him Into Line

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

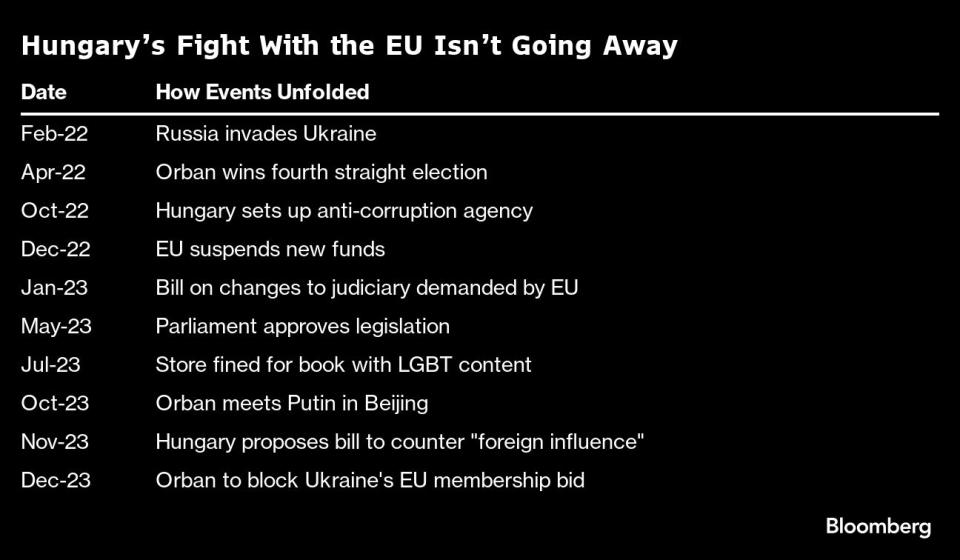

(Bloomberg) -- When the European Union suspended more than $30 billion of funding for Hungary last year, it was seen as a breakthrough moment for the bloc. The thinking in Brussels and around Europe went that withholding such a sum would finally bring renegade Prime Minister Viktor Orban to heel.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Carlyle’s Rubenstein Is in Talks to Acquire Baltimore Orioles

Elon Musk's SpaceX Valued at $175 Billion or More in Tender Offer

Harvard, Penn Heads Walk Back Genocide Answers After Backlash

Wall Street’s AI Craze Drives Nasdaq 100 Up 1.5%: Markets Wrap

A year on, the EU could unfreeze about a third of the suspended money as soon as next week after Hungary appears to have met an initial set of conditions to reduce political interference in the courts. But there’s little to suggest that anything has managed to throw Orban’s decade-old campaign against liberal democracy into reverse.

The reality for the EU is that, unlike with the nationalists in Poland, its threats have emboldened rather than undermined Orban — and the signs are everywhere.

The 60-year-old premier, the EU leader who is closest to Russian President Vladimir Putin, is blocking proposals to amend the EU’s budget, boost aid to Ukraine by €50 billion ($54 billion) and invite Kyiv to start membership talks. The recalcitrance risks torpedoing an EU summit next week. Meanwhile, Orban remains a catalyst for other disruptors, from a new government in Slovakia to the far right that’s aiming to form one in the Netherlands.

At home in Hungary, billboards ridiculing Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, are ubiquitous, the latest iteration of the government’s campaign against the EU, which has funded the economy to the tune of more than €100 billion over the past two decades. A new agency to track foreign influence is in the works, which the remaining independent media and NGOs in the country say is designed to stifle them further.

“Hungary doesn’t want to be the pupil of another power, it wants to be its own master,” Orban said in a foreign policy speech in Budapest on Tuesday. “We need to be radical to succeed.”

Charles Michel, who organizes EU summits as the president of the European Council, traveled to Budapest last week in an effort to persuade Orban to compromise on Ukraine. French President Emmanuel Macron will also take a shot at salvaging the EU’s Dec. 14-15 summit when he hosts Orban for talks in Paris on Thursday.

By freezing money, the EU’s aim was to push Orban to re-build some of the democratic guardrails after years of appeasement, legal wrangling and the threat of suspending Hungary’s vote in the bloc failed to bring him into line. Transparency International rates Hungary as the most corrupt nation in the 27-member EU in its latest annual rankings.

Instead, Orban has extended his influence over all walks of life, from business and media to education and culture via a close network of associates. Another landslide election victory last year in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine cemented his power just months before EU funds were paused.

The EU set out 27 so-called super-milestones for Hungary. The demands cover everything from shielding court independence to protecting academic freedom and LGBTQ rights. Under an Orban law, for example, books with LGBTQ content must be wrapped in plastic at stores in Hungary under the threat of fines.

The trouble, though, is that the EU can only scratch at the surface with legal threats, according to Edit Zgut, assistant professor at the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw.

“The linchpin of the Orban regime is that it fosters a chilling effect, intimidation, and coercion informally, which legislative changes alone cannot address effectively,” she said.

Orban’s government in Budapest, which has ruled by decree since the Covid pandemic, says it’s being unfairly targeted, arguing that there’s no clearly defined rule of law standards to which all member states need to respect in the EU.

To allay EU concerns, the government agreed to grant an oversight panel of judges more sway to resist politicized appointments, automate case allocations at the Supreme Court and remove obstacles for judges to refer cases to EU courts.

In a boost to Orban, the changes were endorsed by the head of the National Judiciary Council, led by a judge who himself has been a target in pro-government media for calling out attempts at manipulating the courts.

“We fulfilled all the criteria so we have the right to get access to the EU funding,” Tibor Navracsics, Hungary’s minister in charge of EU funds, said in an interview at his office in the Hungarian capital on Tuesday.

The sense in Brussels is that Orban has ticked the boxes in terms of legislative changes involving the courts, though it’s not a done deal and officials are completing an assessment.

If confirmed by the European Commission, though, Hungary will unlock about €10 billion, according to EU officials. That’s in addition to €1 billion Hungary received recently along with other members. The rest of the funds earmarked for Hungary will remain under lock until other conditions are met.

Pushing back against critics, EU Budget Commissioner Johannes Hahn told a European Parliament hearing on Hungary that the EU’s executive needed to adhere to the rules when deciding whether to free up funds. Otherwise, he said, the EU could be accused of skirting the rule of law in the name of protecting it.

The belief in the EU is that there are enough strings attached to the money being released, according to one diplomat. That’s the optimistic scenario, though.

In Poland, where the pro-EU opposition prevailed in an Oct. 15 election after years of standoff between Warsaw and Brussels, the new government of former European Council President Donald Tusk is expected to be sworn in next week. Compared with Poland, Orban’s system was too entrenched by the time the EU got serious about confronting it, according to Zgut.

Orban mastered the art of complying with formal EU demands without threatening his grip on power, a dangerous precedent that others are looking at inside the bloc as a template, said a former high-ranking government official of another EU member state who dealt with Hungary regularly.

In the Netherlands, far-right lawmaker Geert Wilders pulled off a surprise victory last month, with Orban one of the first to congratulate him. In Slovakia, Robert Fico returned to power by channeling Orban, targeting critical media and civic groups and raising questions over aid for Ukraine.

“The EU has achieved nothing,” said Akos Hadhazy, an opposition lawmaker who has blamed EU funds for financing Orban’s power consolidation. “The only thing the EU can do is to do no harm. That means not going back to the period when it financed Orban’s regime.”

For now, there appears to be a breakdown of trust between Orban and the European Commission, according to a senior EU official. Finding a compromise is also made harder by the fact that there’s no single leader in the EU who can corral member states. Orban, the longest-serving head of government in the bloc, is exploiting that, the official said.

The best the EU can do is to get tougher, said Zgut. “The EU Commission needs to go back to the drawing board,” she said. “It requires a holistic approach: the EU has to put more emphasis on implementation and law enforcement.”

--With assistance from Andrea Dudik, Alberto Nardelli, Jasmina Kuzmanovic, Daniel Hornak, Andras Gergely, Natalia Ojewska and Veronika Gulyas.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Salesforce Signals the Golden Age of Cushy Tech Jobs Is Over

How the Biggest Boutique Fitness Company Turned Suburban Moms Into Bankrupt Franchisees

Hottest Job in US Pays $80,000 a Year, No College Degree Needed

SpaceX’s Colossal Starship Sets Pace in Race to Build Larger Rockets

The Untold Story of a Massive Hack at HHS in Covid’s Early Days

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.