Will Oregon’s winter be snowy, wet or dry? Strength of El Niño will likely play a role

Editor's note: This story was originally published in November. We are republishing it as we look back at some of our most-read stories of the year.

One thing we know about Oregon's winter this year is that it's going to be influenced by El Niño — the warming of the Pacific Ocean that fuels weather in the Northwest and around the world.

The major question? How strong this El Niño will become, because that could tell us whether there will be flooding, drought or snow in the mountains.

Currently, there’s a 70% chance of a moderate to strong El Niño that traditionally brings warm and dry conditions. Yet there’s also a 30% chance of a very strong El Niño developing that traditionally brings lots of rain, including the type of atmospheric rivers that can cause flooding.

“Right now we’re right on the borderline, and it will be something to watch carefully because it can make a big difference,” state climatologist Larry O’Neill said during the latest episode of the Explore Oregon Podcast.

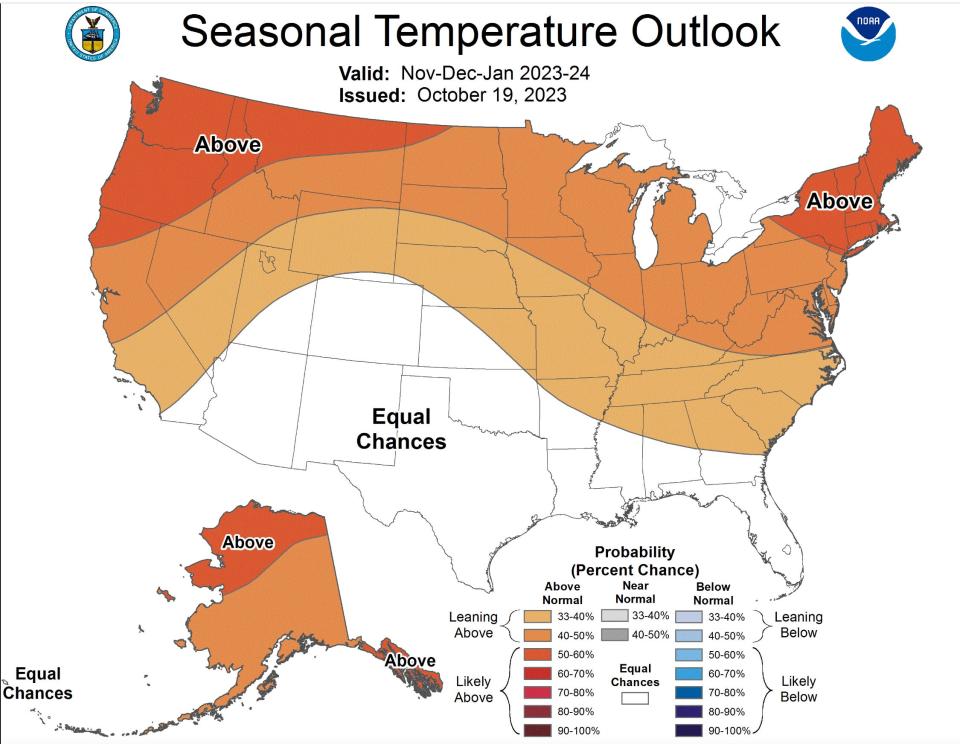

The one thing both "strong" and "very strong" patterns portend is warmer temperatures and less mountain snow. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration long-term forecasts currently place the odds of a warmer-than-normal winter at 50-70%.

“I hate to dash anyone’s hopes of being able to get out skiing or anything like that, but (less snow) is a distinct possibility,” O’Neill said. “Every year is a bit different … But I think having a less robust snowpack this year is a more likely outcome.”

Here’s the full forecast on the upcoming winter from the conversation with O’Neill. Answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Zach Urness: Start by reminding us what El Niño actually is. What does it mean and how does it form?

Larry O’Neill: In a very basic way, El Niño is just a change in the temperature of the ocean in the Equatorial Pacific. So in the Pacific Ocean, near the equator, there's a spot that's usually a little bit colder than all their other surrounding spots. But during an El Niño, that spot gets really warm and it's due to change in the wind patterns. And so why in the Pacific Northwest do we care about what happens at the equator? The reason is because this change in temperature actually causes a cascade of events that shifts our jet stream. It changes (weather) activity and where storms come. It also changes patterns of drought and wildfire risk. It increases flooding chances in certain places. So it really has a big impact on our hydrological cycle and the temperatures and things that we get during the wintertime, at least in the northern hemisphere.

Urness: So this winter, we're locked into an El Niño system. But you mentioned that we're still unsure if it's going to be a strong or a very strong El Niño, which can make a big difference. Can you parse that out?

O’Neill: We are locked into an El Niño of some strength. And when we say a strong or very strong, we're referring to how warm the ocean gets there. And the reason we care about exactly how warm it gets there is that there's a pretty big difference in our historical data records on what the impacts on the Pacific Northwest or the U.S. West will be.

Right now, there’s a 70% probability that what we get is characterized more as a strong El Niño. So during a strong or moderate El Niños, the Pacific Northwest tends to be drier and warmer than normal. And this is based on about 13 to 15 events in the past.

There is some diversity among each individual El Niño, but if you look at the collection of it, it's tilted a little bit more towards warm and dry. It also impacts our snowpack. So we tend to get a little bit less snow. That's not a complete truth for all the El Niños, but it's a tendency for that.

Urness: You were just talking about how a strong El Niño typically brings warmer and drier weather. So what if it gets ramped up and we have that very strong El Niño. What does that normally bring about?

O’Neill: A very strong Niño is one in which the temperatures in the Pacific Ocean are much, much warmer than normal, almost historically warm. We've had three such events since 1950. Each of those three events have bucked the trend of what we typically expect for El Niños. All three of those have resulted in much higher amounts of precipitation than normal in western Oregon and western Washington and parts of northern Oregon, too. So there's this big gap in what we can expect based on historical conditions.

Urness: Which way is it trending now? It’s been very rainy lately. Is that an indication of a strong or very strong El Niño?

O’Neill: This weather isn't necessarily an omen one way or the other. It's actually great that we're getting the rain right now, but at this point it doesn’t mean too much. I would say Christmas. If come Christmas, temperatures in the Pacific warm a bit more and then we start to see these lineup of storms, that would be the clue about reaching that very strong threshold.

Urness: So the question here is "are we going to get a lot of rain or be fairly dry?" That’s what we’re talking about because both scenarios are normally warmer than normal, correct?

O’Neill: Yeah, that is in both categories we're warmer than normal. That is a more robust outcome of being a moderate, strong or very strong El Niño is that we are warmer than normal.

Urness: One of the last very strong El Niños was 2015. We talked about how last time it was a historically small amount of snow, but the rain was decent. So was that an example of a very strong El Niño that we could potentially see this year?

O’Neill: I hate to dash anyone’s hopes of being able to get out skiing or anything like that, but (less snow) is a distinct possibility. Every year is a bit different. There have been cases where we've had a strong El Niño and snowpack has been pretty good. But I think having a less robust snowpack this year is a more likely outcome.

Urness: But that can also be wrong at the same time?

O’Neill: It's not an absolute, it's not 100%. So being in El Niño, it will kind of weight the dice a little bit more towards a leaner snow year.

Urness: What are some other implications? Because it does seem a pretty big deal if we’re a lot more wet. That seems good for water storage, for wildlife, but also feels like a danger for flooding.

O’Neill: Yeah, that's right. And as far as flood risk goes, one of the things about (very strong) El Niños is that we tend to get more atmospheric rivers. An atmospheric river is just a cold front or a storm system that comes through, but it has a tap into moisture from the tropics. And so we tend to get more rain with those. And the thing about atmospheric rivers is that not only do we tend to get more rain, but they also tend to be really warm. If we do have a snowpack up there, you get this big rain on snow event and that's usually when we get some of our bigger flood events. So there is a little bit more of a chance that something like this happens. Like I said, it's not a huge trend one way or the other, but it is something to look out for."

Urness: So make sure to have your flood insurance?

O’Neill: Yes, absolutely.

To listen to the entire podcast, visit https://www.statesmanjournal.com/outdoors/explore/.

Zach Urness has been an outdoors reporter in Oregon for 15 years and is host of the Explore Oregon Podcast. He can be reached at zurness@StatesmanJournal.com or (503) 399-6801. Find him on Twitter at @ZachsORoutdoorst.

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Will Oregon’s winter be snowy, wet or dry? El Niño forecast key