Ortralla Mosley’s mother sought help for her daughter’s killer. She’s done trying.

Editor’s note: This article describes abusive dating relationships and the violent murder of a high school student. Call the National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline at 866-331-9474, text “LOVEIS” to 22522 or visit loveisrespect.org for immediate, confidential assistance.

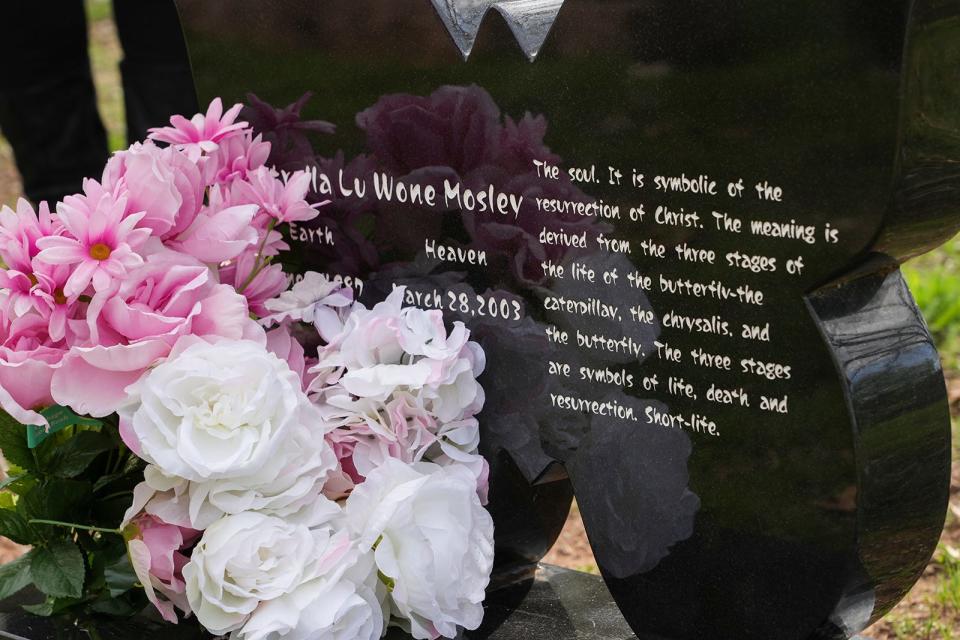

Ortralla Mosley loved butterflies. They were proof that even the ugliest little green worms could transform into something vibrant and free.

Anyone could change.

Carolyn White-Mosley wanted to believe that, too, about the young man who put her daughter in her grave 20 years ago this week, in a shaded spot at Evergreen Cemetery marked by a black butterfly-shaped headstone. Marcus McTear was only 16, dangerously troubled and crying out for help in 2003 before he stabbed Ortralla, his 15-year-old ex-girlfriend, in a hallway at Reagan High School (now Northeast High School).

While the community reeled from the first — and to date only — murder of a student on an Austin school district campus, White-Mosley extended uncommon compassion toward her daughter’s killer. She even supported the courts treating McTear as a juvenile instead of an adult, hoping he would get treatment.

“I still love you, baby,” White-Mosley tearfully told McTear at a 2003 court hearing. “I just hate what you did.”

Now comes a fresh reckoning: McTear, halfway through his 40-year sentence, has his first shot at parole. At 36, he has spent his entire adult life locked up.

He has been punished. But has he grown?

Ortralla’s murder helped bring a sea change in the way that schools in Austin — and eventually schools statewide — handle the threat of teen dating violence.

The tragedy also transformed White-Mosley. She evolved into a prison guard, an advocate and a mentor to countless students, though she will never outgrow the grief of losing such a spirited daughter.

“That was actual love walking,” she said of Ortralla.

For years, White-Mosley felt bound by the promise she made to Ortralla before the stabbing, as McTear grew more erratic. She vowed to get McTear help. She kept trying after his arrest and conviction.

“I’m done,” White-Mosley told me recently, in such pain that her voice became a whisper. “But I tried.”

Invoking justice and mercy

Before the murder, McTear was a popular football player and member of the high school choir. Now, he is an inmate at Memorial Unit, a lockup that houses up to 1,600 prisoners near the farmlands of Rosharon, south of Houston.

White-Mosley hasn’t seen him in more than 15 years. But she wonders: “How does he feel, today? Does he sleep at night? Does he have dreams? Does he see Ortralla?”

The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, which is expected to make a decision on McTear’s fate in the coming weeks, has a good idea of how he’s spent the past two decades.

The parole board knows whether McTear obtained his high school diploma behind bars; whether he benefited from any rehabilitative programs, including one for violent offenders; whether he studied in a prison ministry program; whether he made use of the prison’s career training programs on air conditioning or refrigeration repair; whether he worked in any part of the Memorial Unit’s agricultural operations, which include everything from packaging eggs to raising pigs; and what disciplinary actions, if any, he has faced over the years.

I am not able to find out any of those things. By law, Texas inmates’ records are confidential, apart from basic information such as an inmate’s name, prison facility, crime and sentence.

I exchanged a couple of letters with McTear, who said he was interested in talking, just not at this time.

But he chose to engage on one question: What should justice look like for Ortralla’s family and for him?

“At the end of the day, God’s justice is what matters the most,” McTear wrote, invoking a passage from the Book of Isaiah: “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways.”

He also described God offering comfort to those “in exile for their sin.”

“I strive now, even though I fail at times, to see God's justice and all else He has for me and those I encounter,” McTear wrote.

I didn’t ask about mercy. But he used the word twice.

The loudest alarm bells

White-Mosley wonders: Where was the mercy for Ortralla? She dropped her daughter off at school on March 28, 2003, a Friday morning. The next time she saw Ortralla was two days later, in the morgue.

“They tried to cover it,” White-Mosley whispered through tears. “But I could see the stab wounds in her head. … She was cold and hard and couldn’t hug me back. But she was still beautiful.”

The teens had a stormy relationship, with McTear trying to control what Ortralla wore and which friends she hung out with. As Ortralla tried to break things off in mid-March, McTear pushed his way into her home, grabbed a knife from the kitchen and made a small cut into his neck, White-Mosley said.

Then on March 26, two days before the murder, McTear asked to meet with White-Mosley and tearfully begged for help. As she drove him home, she said, McTear “tried to jump out of the car in front of an 18-wheeler.” She yanked his arm while Ortralla, from the backseat, pulled on the neckline of McTear's shirt. In the commotion, the car hit the curb.

His father, Joseph McTear, was sitting in the garage as they reached the house.

“I said, ‘Sir, your son just tried to kill himself. I’ve got a place (for mental health treatment) for him to go,’” White-Mosley recounted to me. She said she even offered to pay for it. “He said: ‘You take care of yours, and I’ll take care of mine.’”

Joseph and Dorothy McTear did not return my calls about the case. But there were signs back then of a tense home life: Joseph McTear had convictions for hitting another son, then 8, with an extension cord and phoning in a bomb threat to a company that fired him. Later in court, after Marcus McTear had killed Ortralla, the judge noted that Dorothy McTear seemed more interested in consoling her agitated husband than her son.

White-Mosley later sued McTear's parents and the Austin school district for failing to address Marcus McTear’s disturbing behavior. Ortralla and a previous girlfriend had both complained to school administrators at Reagan. The McTears paid $300,000 and the school district paid $165,000 to settle the lawsuits.

The threats of suicide should have set off the loudest alarm bells, said Scott Hampton, a New Hampshire-based psychologist and executive director of Ending the Violence, which provides counseling in county jails to perpetrators of domestic violence or sexual assault.

In an abusive relationship, Hampton said, the victim is at greater risk of being killed if the perpetrator is talking about suicide than if the perpetrator is talking about homicide.

“If I'm actually at the point of thinking of taking my own life, what I'm saying is I'm willing to give up everything. … You're not going to talk me out of it, and I'm certainly not going to take that trip by myself,” Hampton said, describing that desperate mindset. “You think I'm going to leave my girlfriend or my wife for some low-life to scoop her up once I'm gone? I'm buying two one-way tickets.”

Read more

Sharing Ortralla Mosley’s story turned teacher’s grief toward helping others

Time, distance and prison walls haven’t stopped Ortralla Mosley’s killer from reaching out

A chance to change

Hampton saw a flicker of hope in Marcus McTear’s decision in 2003 to admit his guilt in juvenile court for Ortralla's murder. McTear was sent to a youth corrections facility. If he successfully completed the rehabilitation program there, he could have been eligible for parole after three years instead of going to adult prison for decades.

“Despite how this kid started, he actually had a working compass in there,” said Hampton, who looked at the case at my request. “It just hadn't been deployed yet. And he was asking for help.”

But would he get it? White-Mosley went to prison in 2005 to try to find out, working for about a year as a prison guard at the George Beto Unit in East Texas.

“I went in there to figure out, and to hear and to see: What do prisoners do, now that I have a prisoner in my life?” she told me recently. “What do they do? What do they eat? Do they sleep? And are they getting help? Are they getting counseling?”

And why, she wondered, does every inmate find Jesus?

“Is that the only thing in prison that they got?” asked White-Mosley, herself a woman of faith.

Then she saw: The inmates find each other. She saw some of them coach each other in the worst ways.

“They’re bettering each other’s crimes,” White-Mosley said. “They’re discussing, ‘I would have done it better this way, man.’”

The public’s last glimpse of McTear’s journey came in January 2006, when the Texas Youth Commission petitioned a judge to transfer the 19-year-old to an adult prison because he wasn’t making enough progress in his treatment.

Just six months after the murder, McTear told staff at the youth facility that he had forgiven himself and was ready to get on with his life, according to records discussed in the hearing.

McTear had been living at a youth facility that housed boys and girls separately. Three girls there became McTear’s girlfriends, a prosecutor said. He sent notes exhibiting controlling behavior to at least one of them.

Sometime after McTear moved to a men's prison in the Texas Panhandle, either in 2006 or 2007, White-Mosley drove hours for what she was told would be an apology. Instead, she said, McTear read from a one-page letter that was long on self-pity and short on personal responsibility.

"I said, 'You brought me almost 800 miles (round trip) to read this damn letter to me?'" Then she repeated what she had told him in court: "I forgive you. I'll never forget what you did." And she walked out.

A letter arrived several years ago with a return address "on behalf of Marcus McTear." White-Mosley couldn't bring herself to open it or to throw it away. She tossed it in a pile with some junk mail.

I asked if she still had it. "It's probably in a big box somewhere with a bunch of other stuff," she said indifferently.

Dating abuse is a pattern of coercive, intimidating, or manipulative behaviors used to exert power and control over a partner. Such behaviors by an abusive person may include:

• Checking your phone, email or social media accounts without your permission

• Putting you down frequently, especially in front of others

• Isolating you from friends or family — physically, financially or emotionally

• Extreme jealousy or insecurity

• Explosive outbursts, temper or mood swings

• Any form of physical harm

• Possessiveness or controlling behavior

• Pressuring or forcing you to have sex

For support, call the National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline at 1-866-331-9474, text “LOVEIS” to 22522 or visit loveisrespect.org.

SAFE offers Expect Respect support groups in some middle and high schools to help young people who have been exposed to violence in the community, at home or in peer relationships. All services are free, confidential and provided at school during the day. To learn more, or to talk to someone about teen dating violence, email expectrespect@safeaustin.org or contact the 24-hour SAFEline at 512-267-7233; text 737-888-7233; or chat at safeaustin.org/chat.

Source: Love is Respect, a project of the National Domestic Violence Hotline

Helping other youths

White-Mosley found it easier to change institutions than to change one young man.

Working with White-Mosley and domestic violence experts, the Austin school district became one of the first to create a dating violence policy that included training for teachers and administrators, counseling for students and a process to separate teens entangled in a toxic relationship.

White-Mosley and other advocates then urged the Legislature to require such plans of schools statewide. By then, they were joined by Elizabeth Crecente, the grieving mother of Jennifer Crecente, an 18-year-old Bowie High School senior who was killed in 2006 by her ex-boyfriend in a wooded area between their homes.

In 2007, with a bill authored by then-Austin Rep. Dawnna Dukes, “Texas became one of the first states in the nation to require all schools to have (a dating violence) policy in place at all their campuses,” said Agnes Aoki, the counseling director of Expect Respect, a program by the SAFE Alliance to prevent youth abuse and violence. “That was really huge.”

Ortralla wasn’t the first teen to die at the hands of an ex. But her death on campus, after so many missed opportunities to intervene, forced schools to acknowledge the problem.

“It took a tragedy like that in order for it to be important enough for schools to even think about what they could do,” Aoki told me. “It was so unfortunate that it occurred on a school campus, but if it hadn't, schools wouldn't be talking about it.”

White-Mosley's work with other advocates also led to expanded measures on teen dating violence being included in the 2005 and 2013 reauthorizations of the Violence Against Women Act, culminating in an emotional meeting in 2013 with then-Vice President Joe Biden. She can see that people have training and support that didn't exist 20 years ago. Even in death, Ortralla helped others.

In recent years, White-Mosley has devoted herself to overseeing after-school learning enrichment programs that offer everything from chess to welding to robotics.

“That's where my joy comes in,” she said, “working in (a school district), helping children, seeing them smile, getting emails once they graduate or they’re on the way to college saying, ‘Miss Mosley, I appreciate you for pushing me.’”

Her solace comes from visiting Ortralla’s plot on the eastern edge of Evergreen Cemetery. She feels her daughter’s spirit in the soft winds that lift the branches of the oak and pecan trees. In time, a butterfly dances by.

White-Mosley is at peace with her decision to forgive McTear. But when she finally gets her meeting with a member of the parole board on Tuesday — the exact anniversary of her daughter's murder — her message will be: He's not ready for release. He needs to spend more of his life paying for the one he took.

“I need him to spend that whole 40 years” in prison, she said.

Grumet is the Statesman’s Metro columnist. Her column, ATX in Context, contains her opinions. Share yours via email at bgrumet@statesman.com or via Twitter at @bgrumet. Find her previous work at statesman.com/news/columns.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Ortralla Mosley's mother opposes Marcus McTear's first shot at parole