When the Oscars Were Seduced by X-Rated New York City

A dimpled, fresh-faced young guy from Texas arrives at the Port Authority Bus Terminal on 42nd Street, the sleazy heart of New York City, looking for love and money. Joe Buck wanders the streets in a faux cowboy outfit, watching jaded New Yorkers make their way around a man in a suit lying prostrate on the sidewalk outside Tiffany’s, and a woman on meth or something worse careening up and down an alleyway while a handful of street people observe her impassively, and a cheerless collection of male hustlers hanging out beneath tawdry movie marquees seeking customers looking for a quickie.

Even more scary to him than the people he observes are the ones he meets: an aging prostitute who relieves him of 20 bucks after an afternoon tryst; a pimply schoolboy who fellates him in the balcony of a sleazy grindhouse, then confesses he doesn’t have the $20 he had promised in return for the sex; and a barfly named Ratso Rizzo with bad lungs and a permanent limp who cons Joe out of another precious twenty.

The Oscars Are Dying. Can They Be Saved?

Welcome to New York City circa 1968, a grim, gritty and predatory town without pity, as portrayed in Midnight Cowboy, the X-rated movie that captures with remorseless realism a once-great city sinking into what looks like terminal decline. The city is seen through the eyes of Joe and Ratso, two homeless, solitary outcasts who come to depend on each other out of sheer necessity. The movie was, according to film critic Rex Reed, “probably the most savage indictment against the City of New York ever captured on film.”

The Oscars take place this Sunday evening, April 25, amid a pandemic that is one of the great crises of the modern age and an artistic and economic challenge to the future of moviemaking and moviegoing. But it’s also an appropriate moment to remember another time, some 50 years ago, when everything about the movie business seemed at risk and Hollywood was sliding toward financial bankruptcy and social irrelevance. Strange as it may seem, one of the movies that rode to its rescue was this bleak tale of two of God’s loneliest men, struggling for survival in an urban jungle.

British film director John Schlesinger came to New York in 1968 to make a movie of James Leo Herlihy’s dark but evocative novel. Schlesinger had had a couple of small but impressive hit films in Britain—most notably Darling (1965), a sharp, semi-satirical takedown of “Swinging London” starring Julie Christie, who was so seductive and charismatic under his direction as a ruthlessly ambitious model that she won an Oscar for Best Actress in her first starring role. Herlihy’s novel had already been rejected as too depressing by a number of Hollywood studios, but Schlesinger liked the idea of portraying New York through the eyes of a naïve, struggling dreamer in part because he himself felt like an outsider. He persuaded Jerome Hellman, a New York-born and bred movie producer, to sign on and together they convinced United Artists, the smallest and most independent of the major studios, to finance the film for a bare-bones $1.1 million budget (which eventually ballooned to three times the original figure thanks to Hellman’s creative bookkeeping). Still, even Schlesinger himself harbored doubts. “Do you really think anyone’s going to pay money to see a movie about a dumb Texan who takes a bus to New York to seek his fortune screwing rich old women?” he would continually ask his cast and crew during the film shoot.

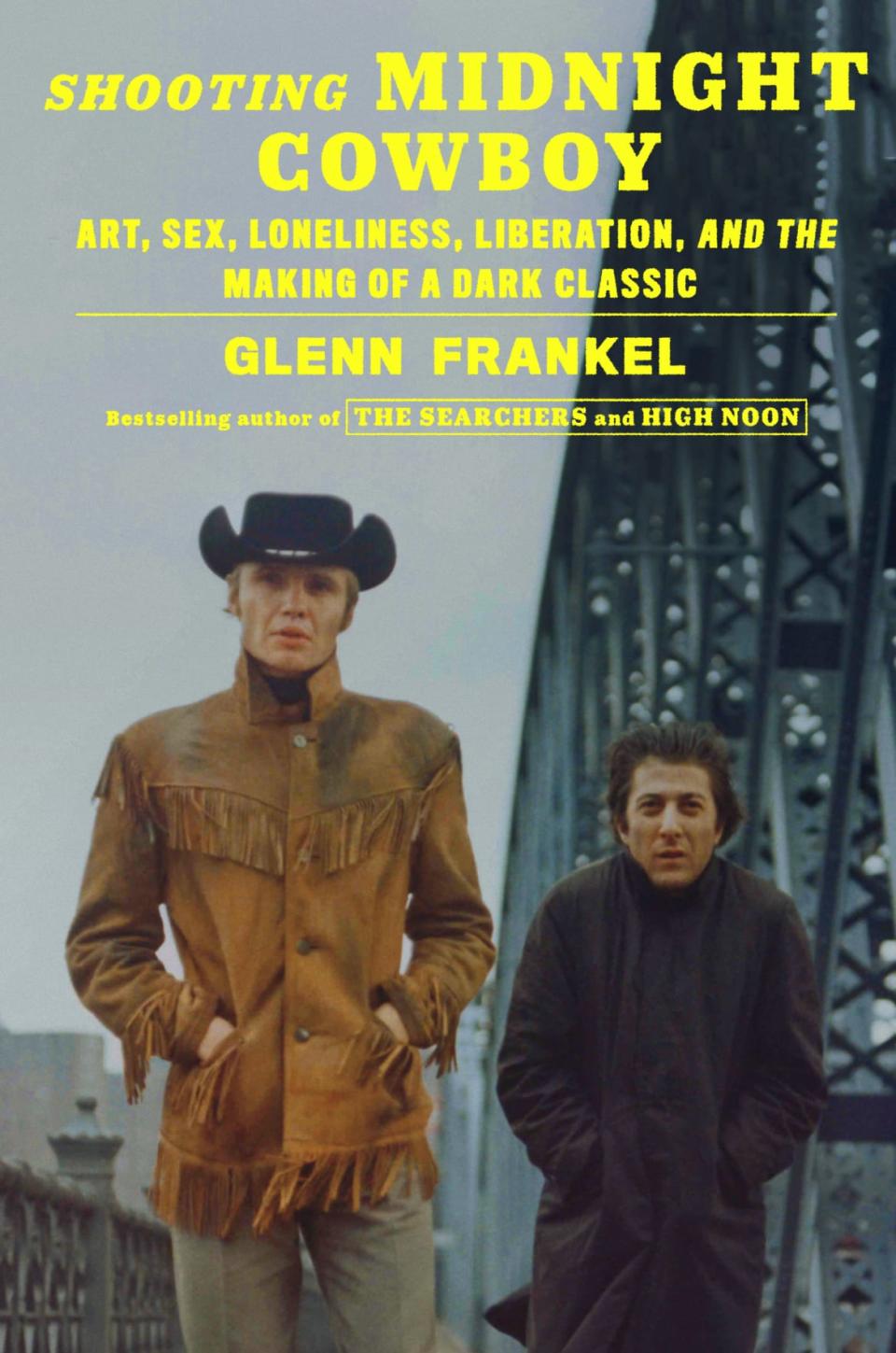

In the end they did. Midnight Cowboy was not only a critical success but became a box office hit, grossing some $44 million and making both Schlesinger and Hellman rich men. There were many reasons for its success: Dustin Hoffman, coming off his first starring role in The Graduate, gave a powerful performance as Ratso Rizzo, cementing his status not only as a fine actor but as a counterculture hero. Newcomer Jon Voight was just as good in capturing Joe Buck’s vulnerability and sex appeal. The supporting cast, recruited by master New York casting director Marion Dougherty, were equally superb. There was wonderful documentary-style cinematography by Polish-born newcomer Adam Holender, memorable outfits designed by Ann Roth, a great screenplay by formerly blacklisted screenwriter Waldo Salt, and sparkling music, anchored by “Everybody’s Talkin’,” sung by Harry Nilsson, and the poignant “Midnight Cowboy” harmonica theme. Younger audiences—the prized target for desperate studios—seemed ready for the adult themes, gay sub-context, and complex characters that the movie featured.

But New York City was the real star of the show. Schlesinger and Holender roamed the streets, filming Hoffman and Voight in set pieces as well as surreptitious “stolen shots” from an unmarked van with a long lens that captured the slowly evolving partnership of the two street people as they moved around town. It wasn’t just the grungy settings—the filthy, unheated Lower East Side tenement set for demolition that Ratso calls home; the 42nd Street blood bank where Joe sells his blood for a few bucks; the coffee shop where a famished Joe makes himself a sandwich from a package of saltines and a bottle of ketchup; the sleazy arcade where he picks up a nervous out-of-town salesman looking for a one-night stand at a cheap hotel. It was New Yorkers themselves, epitomized by Cass Trehune, the hard-bitten prostitute who explodes in anger and self-pity when Joe asks her to pay for their brief tumble in bed (Sylvia Miles won an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress for less than seven minutes of brilliant screen-time); and Ratso Rizzo, when he cries out “I’m walkin’ here, I’m walkin’ here! You son of a bitch!” at a cab driver who barrels into the crosswalk trying to beat a red light. These are quintessential moments that Jerry Hellman says always evoked knowing laughter from New York audiences at every preview.

Midnight Cowboy paved the way for a decade of tough, gritty New York movies that traced the city’s decline, from The Panic in Needle Park and The French Connection (1972), Mean Streets and Serpico (1973), The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975), culminating in Midnight Cowboy’s true fraternal twin, Taxi Driver in 1976, with Travis Bickle, an angry psychopathic U.S. Army veteran cruising the utterly defeated streets that Joe Buck had once explored with wide-eyed wonder. There were powerful, Black-oriented dramas as well, such as Shaft (1971), Superfly and Across 110th Street (1972) featuring drug dealers, corrupt cops, and memorable musical soundtracks.

Oscar night 1970 was an ambiguous event that illustrated the anxieties and uncertainties besetting not just the movie business but the country as a whole. Gregory Peck, the leading-man-handsome president of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences, introduced the festivities with ponderous questions about the new freedom of expression, while master of ceremonies Bob Hope cracked homophobic jokes about Richard Burton playing a gay hairdresser in Staircase and about the movie version of The Boys in the Band, one of the first mainstream openly gay melodramas. “This will go down in history as the cinema season which proved that crime doesn’t pay but there’s a fortune in adultery, incest, and homosexuality,” sneered Hope.

You Now Have Zero Excuses for Not Watching the Oscar Nominees

John Wayne, a proud Neanderthal conservative, won Best Actor for True Grit, defeating Hoffman and Voight, both of whom were nominated. But Midnight Cowboy went on to win three major Oscars: Best Picture, Best Director for Schlesinger, and Best Adapted Screenplay for Waldo Salt. Schlesinger was too nervous to be there; he stayed in London where he was shooting his next film, Sunday Bloody Sunday, which was even more sexually frank than Midnight Cowboy. But Waldo Salt in his acceptance speech summed up nicely what the picture, a groundbreaking movie when it came to depicting a city and its most desperate, neglected denizens, really meant to Hollywood. “I want to thank all of the beautiful people who helped make Midnight Cowboy,” he declared. “Most of all, I want to thank all the people who are going to see it. May their number increase.”

Glenn Frankel is a former Washington Post journalist and Motion Picture Academy Scholar. This article is adapted from Shooting Midnight Cowboy: Art, Sex, Loneliness, Liberation, and the Making of a Dark Classic, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.