How OSU physicists developed a radiation detector aboard the International Space Station

The persistence of a pair of Oklahoma State University scientists to ensure the successful installation of a working radiator detector on the International Space Station paid off last month.

Eric Benton, a professor in the Department of Physics within OSU’s College of Arts and Sciences, and doctoral student Tristen Lee learned then that the detector they designed and built now is transmitting information back to Earth. The successful installation came after accidents foiled two previous attempts.

“This is the biggest thing I’ve done in my life so far,” said Lee, who enrolled in Oklahoma State University’s physics department in 2019 specifically to conduct research with Benton. “The work itself was gratifying, but to see the launch go successfully, it was like a big weight lifted off my shoulders. And then to see the first round of data come back and realize I’m going to get a Ph.D. out of this? Yeah, it was a feeling of relief and then satisfaction.”

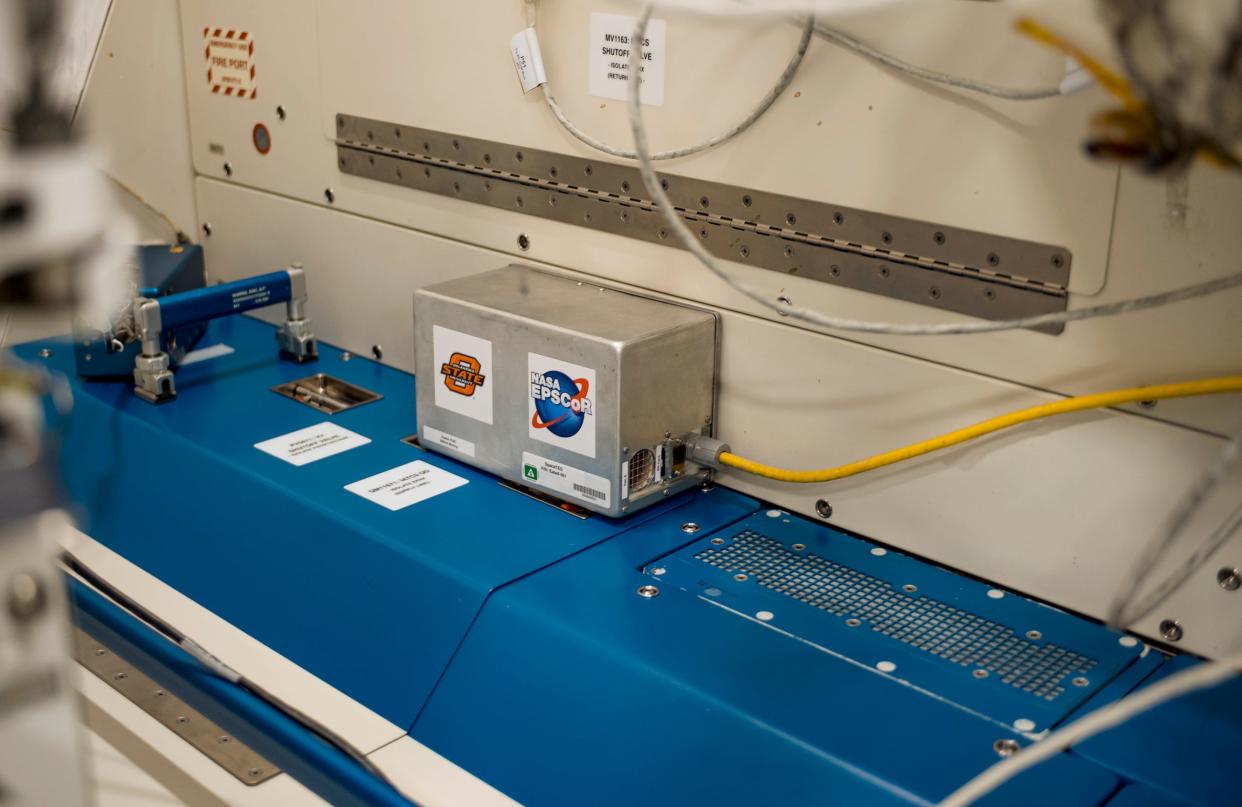

The detector is known as SpaceTED, which stands for Space Tissue Equivalent Dosimeter, and its design was funded by NASA through a federal grant known as an Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) award.

What does the SpaceTED do aboard the International Space Station?

About the size of a child’s shoebox, SpaceTED is designed to mimic the response of human tissue to ionizing radiation. Every couple of weeks, Lee and Benton receive new data from the detector.

“This allows for more accurate measurements of radiation doses that could be delivered to the human body than from, say, a Geiger counter,” Lee said. “It’s essentially two columns of numbers, with each row in those columns representing the amount of energy deposited by ionizing radiation in the detector. We had 38 hours of data in the first batch, which was about 1,700 files.

“We’ll put the data through various conversion routines, and it will give us what’s called the absorbed dose. This is a quantity used to measure the amount of radiation a person receives — whether it’s from X-rays at the dentist or space travel.”

Closer to home, the research conducted by Benton and Lee could help others who fly frequently at high altitudes and receive higher doses of radiation than people on the ground. As of now, regulating acceptable radiation exposure for frequent flyers is based on estimates and computer models.

“But the computer models have not been validated very well with actual measurements,” Benton said. “The work that NASA is sponsoring is largely in support of getting those measurements.”

A long history between OSU and NASA

OSU physicists have a long history of working on space- and radiation-related projects. In 2005, researcher Steve McKeever helped create a device to help astronauts floating in space visually detect radiation, a project that took flight during that year’s mission of the space shuttle Discovery.

Benton has worked on projects funded by NASA grants since 2007, and earlier prototypes of SpaceTED and other radiation detectors line his office. He said the first radiation detector meant to be used at the International Space Station was destroyed when a delivery truck was involved in an accident and burned. In 2018, another detector made it to space, but an astronaut accidentally kicked it and damaged the device’s SD card drive, rendering it inoperable.

Lee drove the current model to Houston himself. The detector now is installed in the Japanese Experiment Module aboard the space station.

“Fortunately, they gave us a second chance,” Benton said. “The first thing I did after receiving the news that the detector was kicked was write this huge list of lessons learned and all the things I’d do differently. I handed it to Tristen and said, ‘OK, build a better one.’ And he did.”

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: OSU physicists' radiation detector aboard International Space Station