How Have Leading Athletes Addressed Their Struggles With Mental Health?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

We’ve all heard about the diets and fitness regimens that keep athletes in fighting shape; from Novak Djokovic’s ascetic eating habits to LeBron James’s lengthy daily workout routine. But how do those same figures keep their mental health in check? Declining to do the traditional post-match press at this year’s French Open, Naomi Osaka shone a light on that issue, citing her struggles with mental health as she withdrew from the tournament in June. (Let’s set aside, for a moment, the debate that she has also fueled around the role and responsibilities of athletes vis-à-vis the press.) The gymnast Simone Biles, moreover, has recently done the same, stepping away from the women’s team gymnastics final at the Tokyo Olympics on Tuesday. “It hurts my heart that doing what I love has been kind of taken away from me to please other people,” she explained to reporters, describing the high stress of competing. “[The team was] totally prepared, but it just sucks when you’re fighting with your own head. Like, you want to do it for yourself but you’re still too worried about what everybody else is going to say.” At the end of the day, she added, “I have to do what was right for me.”

The nonprofit Athletes for Hope has estimated that 35% of professional athletes experience problems with their mental health, facing everything from eating disorders and burnout to depression and anxiety—but they’re not often discussed on the world’s largest stages, especially not by players at the top of their careers. (Osaka is currently ranked second in the world by the Women’s Tennis Association, with a net worth of some $25 million.)

Over the last 30 years, it’s been rather more common for athletes to describe their mood disorders or bouts of mental illness after their retirement, when certain public and professional pressures had eased. The former NHL goaltender Clint Malarchuk is one example: In 2019, he described the symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that followed a horrific game-time injury in 1989. “I’d sit straight up in a chair so I wouldn’t go into a deep sleep,” he told the CBC of the ensuing months, “so I wouldn’t visualize in a dream the flashback of that skate coming up and cutting my jugular vein.” Long after leaving the NHL in 1996, he still wrestled with anxiety and alcohol abuse, ultimately . He was only diagnosed with PTSD when he subsequently entered rehab.

Buffalo Sabres

Returning to the ice just 10 days after his incident, Malarchuk said that he wasn’t offered counseling of any kind to cope with its effects. “None was provided. I didn’t think of it back then, nor did they,” he recalled. But following the release of his 2014 autobiography The Crazy Game, he and his wife, Joan Goodley, worked to raise awareness around obsessive-compulsive disorder, suicide prevention, psychological trauma, and depression among retired athletes.

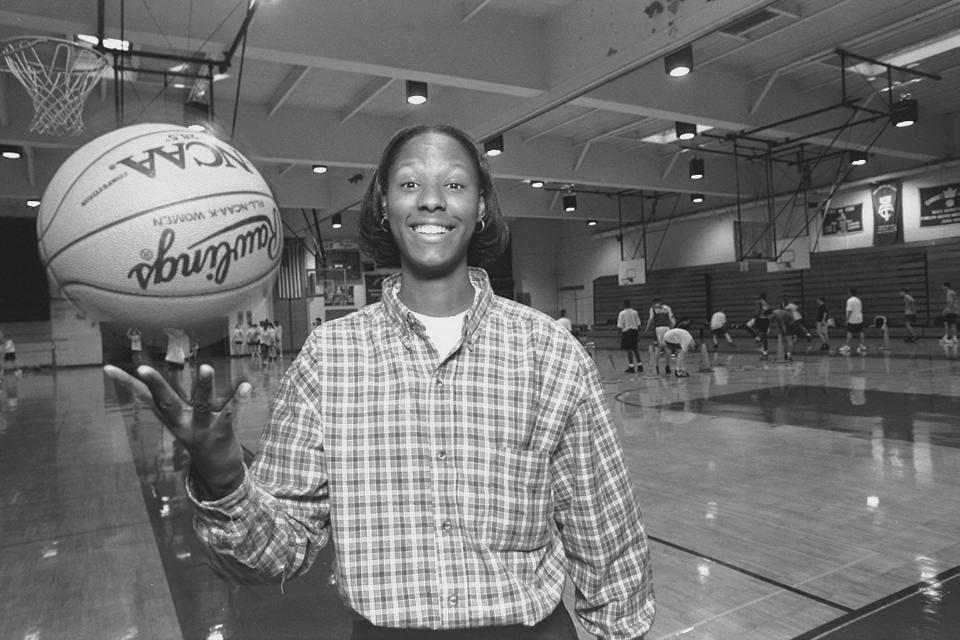

In 2007, the former Olympic ice skater Dorothy Hamill—who had a long history of depression in her family—told CBS that mental illness had dogged her throughout her career. “When you have that goal and you have that dream and it actually happens, you think that it would be a switch,” she said, “and that all of a sudden you’d feel, you know, like an Olympic champion. And I didn’t feel any different.” Chamique Holdsclaw, a former WNBA player, revealed her own diagnoses of clinical depression and bipolar disorder in Breaking Through: Beating the Odds Shot After Shot, her 2012 autobiography. “You get labeled as a quitter with mental health issues like mine,” she told the Washington Post in an interview that year. “People would say I was an ‘enigma.’ Or a ‘problem.’ All along I knew that wasn’t me.”

Chamique Holdsclaw

Osaka’s reticence around doing press recalls that of another hugely successful young star; the former NFL running back Ricky Williams. When he started with the New Orleans Saints in 1999, Williams was known to give interviews with his helmet on and would shy away from interactions both with fans and teammates. He was ultimately diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, which he addressed with therapy and an antidepressant. “I understand that a lot of people, especially men, look up to me because of my profession, so I have a chance to reach out to people and let them know what I’ve been through and how treatment has made my life so much better,” he said in 2009.

Yet as news came in from Roland-Garros over the weekend, Osaka was more often compared to Michael Phelps, whose battles with depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues were widely reported between the 2012 London and 2016 Rio Olympics. After several years of flagging interest in his sport—even as he collected four golds and two silvers at the 2012 games—Phelps reached a personal nadir after a DUI arrest in 2014. At the time, he had been struggling to reconcile his faltering mental health with the stresses of being an outsized public figure. “I didn’t see me as me,” Phelps told the New York Times in 2016. “I saw me as everybody else did—as an all-American kid. Let’s be honest. There’s not a single human being in the world that’s like that.”

Olympics - Previews - Day -2

Although Phelps retired after Rio, the publicity around his arrest and journey back onto the podium left a sizable impression on the world of sport. In recent years, younger athletes have become increasingly forthcoming about their own challenges. In 2018, the basketball player DeMar DeRozan of the San Antonio Spurs tweeted out about his struggles with mental health, later telling the Toronto Star, “It’s one of them things that no matter how indestructible we look like we are, we’re all human at the end of the day.” The Cleveland Cavaliers’ Kevin Love wrote an essay about his anxiety and depression for The Players’ Tribune, titled, “To Anybody Going Through It.”

While Osaka’s exit from Roland-Garros seemed, to some, a disappointing—and perhaps avoidable—result, it has also confronted an issue that, until now, has been engaged in fits and starts: the emphasis, in the world of professional sports, on physical fitness and performance over mental health.

“I am so sad about Naomi Osaka,” Martina Navratilova said in a statement on Twitter. “As athletes, we are taught to take care of our body, and perhaps the mental & emotional aspect gets short shrift. This is about more than doing or not doing a press conference.”

Originally Appeared on Vogue